After a decade of epistolary exchanges, I finally met Shahzia Sikander, Pakistan’s most celebrated global icon of the arts, ironically unsung at home.

Not to be boxed in, to be able to transcend boundaries: for an artist, it’s essential.

It is a pity that I got to discover Shahzia Sikander’s work only when I left Pakistan. After her initial successes in the 1990s, with her migration to the United States, she slowly disappeared from the local art scene and the narratives within her country of birth, almost rendered invisible, like the mythical characters one reads in the folklore. In a different country, she would be celebrated for being a global icon, intensely original and gifted. Not in her country of birth where talent is subjugated to the cliques that define excellence and where history has to be doctored to make the present legible and comfortable.

As she told me, it was vital to respect and acknowledge the autonomy of the other and this is why multiculturalism does not appeal to her as a reference to her works. Sikander’s hallmark is that she stands out everywhere even when engaging with elements of American, South American and other cultures and never loses sight of their sovereignty.

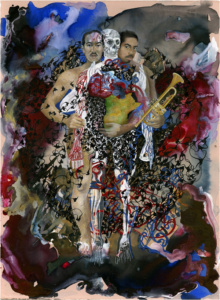

Sikander’s video animation The Last Post, which takes the opium trade and the British East India Company as a point of departure was installed in Norman Foster’s Kogod Hall, a space between Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Sikander says that her process focuses on rediscovering cultural and political frontiers, to create new frameworks for dialogue and visual narrative. Contemporaneity is about remaining relevant by challenging the status quo, not by clinging to past successes. She challenged the traditional and contemporary divide and holds that deconstruction in her narratives is a means to re-imagine historical content and entrenched symbols open the discourse and to challenge and re-examine our histories.

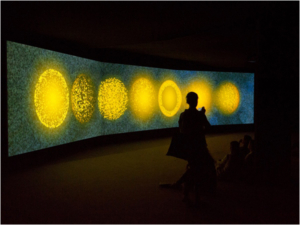

An earlier digital animation SpiNN(2003) satirised cable channel CNN as it highlighted the mass of spiraling, abstracted forms, almost like a swarm of angry black crows or bats that land at a Mughal durbar hall. In turn the hall is full of gopis whose black hairdos turn into the central motif underlying women’s agency. In Unseen Series (2011), large-scale HD projections deal with landscape in the night, where drawings are juxtaposed with architecture and foliage. A multi-armed female form refers to Doris Duke looming over Shangri La; and her majestic home overlooking the Pacific (where her ashes were sprinkled).

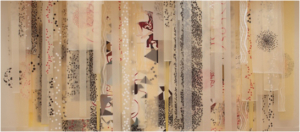

Later in 2011, Sikander travelled to Sharjah to participate in a local biennale. Inspired by the desert and observing the coastline at Hormuz resulted in Parallax a 15 metres long, cinema-sized video installation. The Parallax employed hundreds of miniature drawings and gouaches and turned them into living animations. They replicate and separate and resemble images of soil, sand, water, and blood providing an overview of Hormuz only to transform into flocks of innumerable birds, black oil and then hordes of people. Parallax delineates the narrative of power, control and its complicated relationship with nature.

It is a sign of her success in evolving a unique global language that Sikander’s work is included in the permanent collections across the globe. In the US, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Park, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Philadelphia Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, and many more exhibit her paintings and installations. Outside the US, The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Royal Ontario Museum, Centro Nazionale per le Arti Contemporanea Rome, Bradford City Museum, Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Birmingham Museum, the Burger Collection Hong Kong, MAXXI Museum Rome among others showcase her work. In 2015, Asia Society has honored her for having made a significant contributions to contemporary art.

The honours started with her achieving the Shakir Ali and the Haji Sharif Awards at NCA in 1992. During the last two decades she earned the Art Prize in Time-Based Art from Grand Rapids Museum (2014), the Inaugural Medal of Art by Hilary Rodham Clinton (2012), John D. and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation Achievement Genius award, (2006-2011); SCMP Art Futures Award, Hong Kong International Art Fair (2010), The DAAD, (Berliner K ¼nstlerprogramm, Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) Berlin (2007-08), Tamgha-e-Imtiaz, the National Pride of Honor by the Pakistani Government (2005). The Newsweek in 2004 listed her as one of the most important South Asians transforming the American cultural landscape. In 2006, the World Economic Forum, appointed her as a Young Global Leader and in 2010, Sikander was elected a National Academician by the National Academy in New York City.

Sikander’s two decades of practice has seen three distinct phases: first pushing the boundaries of miniature and subverting the tradition; second the early 2000s where she distanced from the form but not its essence and delved into larger questions of global relevance. Her third and more recent phase is turning her art practice into a three dimensional endeavour where the form holds a dialogue with the content, the artist engages in a discourse with her medium; and the viewer is pulled into that conversation. This is reflected in her recent works such as Parallax and The cypress despite its freedom is held captive by the garden based on a dilapidated cinema Khorfakkan and a Pakistani labourer.

This amazing repertoire, unmatched by any artist of her generation, is nearly invisible in her own country. As Faisal Devji wrote last year in a hard-hitting piece entitled Little Dictators: Sikander’s pioneering work is under threat, being routinely censored. Devji cited two books Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia and Art and Polemic in Pakistan (by Iftikhar Dadi) Cultural Politics and Tradition in Contemporary Miniature Painting (by Virginia Whiles) that ignored the foundational character of Sikander’s work. These are two major art histories of Pakistan and both omit Sikander’s vital contribution to contemporary Pakistani art at home and abroad. Devji added, ..If anyone can break this stranglehold on the narrative of Pakistan’s cultural history, it is Sikander, who achieved global fame in the pre-9/11 world and whose work is not over-determined by the war on terror, itself now an aesthetic commodity. (Feb. 2014, Newsweek Pakistan).

The two authors however denied the deliberate omission and cited research frames for not mentioning Sikander. Devji responded with another long piece on the factionalized art world of Pakistan. Sikander has also been accused of not engaging with Pakistan even though much of her work abroad has referred to the country where she was born and trained; and throughout the world she is known as a Pakistani artist.

This is not surprising. Skipping Sikander’s story is a figment of the larger Pakistani malaise to deny its own history. Reinventing histories and concealing information is a larger trend at work. Take the example of 1971: the memory of the Bengalis, their struggle and independence is something that we have erased. Sikander’s central role in redefining the scope of miniature and globalising its form, acknowledged by the world, is ironically not mentioned in art histories being compiled within the country. Pakistan generally has a problem with its citizens recognized abroad: be it Dr Salam or Malala, there is a strange, complex reaction at work. It has something to do with a country not at peace with its identity and position in the world. Or something else. This merits a separate rant.

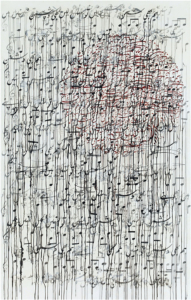

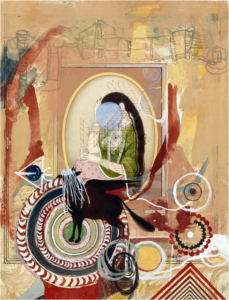

When I arrived at her New York Studio on a freezing December afternoon, I felt as if I had entered into an ocean of possibilities- exhibited, un-exhibited, familiar and unfamiliar. Almost like the magical zanbeel (bag) of the mythical Amar Ayyar. There were grand works in progress, nothing similar to what I have seen. And hundreds of works that inform her installations, projections etc. were scattered. On the right wall, I saw the original Scroll that was unbelievably mesmerizing. It took a few minutes for me to travel within this extraordinary work. We had been exchanging emails over the past one decade and this very first meeting was therefore quite special. I remember sending her an email exactly a decade ago to which she responded promptly. I had seen some of her work and could not believe that powerful ideas could be treated in such a delicate manner.

Sikander’s brush with global academe has also turned her into a unique artist with a formidable verbal expression. I had hundreds of questions and she responded with stories personal, technical and political. It turned out to be one of those conversations where one simply wanted to hear and travel with the narrator: into words, into the syllables, into the subtext. Sikander told me how her own hybrid identity was constantly shifting with the conceptual boundaries she recognised and challenged. Her art therefore was an open-ended conversation with herself and the craft she had innovated over the years.

Slender, tough and brimming with energy, she is an enchanting persona. From the paintings and installations we moved to her computer where she showed me her animations. I have to confess that I have not seen something so original before. Sikander’s craft as a post-miniaturist is so central to her range that one cannot miss the haunting intensity of her lines and strokes. Projecting them on larger scales and in different media transforms the tradition into a totally new artistic style.

Sikander was perturbed about the fact that she was being put through a loss of her own history which she owned. The year 2014 was tough for her with all the commentary by her peers and art critics in Pakistan. She had been accused of catering to the West. I respond to my own quest and medium with which I work, she added. In fact, Sikander’s poignant work entitled, The Resurgence of Islam was painted in 1999 (two years before 9/11) and it remains one of the more nuanced renderings on the subject. My advice was to completely ignore what is said since her work was the best answer to all the jibes and criticism. Sikander agreed but only partially.

Success is not what it is perceived to be. It’s a lot of hard work and almost a hermit-like existence she remarked, when I asked her about her meteoric rise on the global art scene. It’s all push, push, learn to invent all the time, she added. Referring to the process of painting she called it meditative and this is why being a hermit has become her second nature. Looking at her oeuvre, I cannot help but agree. How could anyone produce so much if s/he were not a hermit!

I also saw her recent work that was featured in New York Times. Aptly titled, The World Is Yours, the World Is Mine, it reflects on the news about the Ebola outbreak from Africa to the US and how isolation was being conducted in a globalized world through screenings and quarantines. Playing with the idea of active and dormant microbes, Sikander transports it onto the broader story of how narratives lie dormant until someone culls them from history’s rubble.

Sikander wants to work more on 1971 as a means to familiarise herself with the history that she was not taught. In that process she would perhaps reclaim some of her own histories that have been taken away by the art establishment of Pakistan. The best way to view Shahzia Sikander’s work is to look at the themes of displacement, and the universal need for fictive transport (to borrow the term from artist David Hunt) from the more personalized sense of alienation that clings to each of us.

I am still struggling to grapple with her work and by no means have I engaged with even a fraction of an incredibly vast and rich corpus. The good part is that Sikander has promised to continue the conversation: Both with viewers (such as myself) and with that delicate, layered craft of hers.