The challenge of translating a historical era into a cinematic endeavour is daunting, especially when it concerns historically contested subjects such as the fabled love between 16th century Mughal Emperor Akbar and Jodha Bai, the legendary princess from Rajputana who later ruled India as Empress and symbolised the Hindu-Muslim accord of the times. However, it is not historical accuracy, or lack thereof, which defines the rather exasperating cinematic narrative of an otherwise glorious period of the subcontinent’s history. It is the facile treatment of history, its interpretative variants and its actors that makes the Bollywood film Jodhaa-Akbar a disappointment.

Akbar’s reign symbolised the zenith of the Mughal Empire and also some of its unique attributes. Whether it was the secular, tolerant governance based on the Sulah-i-Kul (peace with all) policy, opening up the frontiers of theological discussion, effective administrative systems or promotion of Indo-Mughal art forms, Akbar was a pioneer in most respects.

Jodhaa-Akbar attempts to capture the essence of that particular moment: the Indianisaton of the Mughal court and most importantly, the royal household. Whether it is to do with the grafting of a temple within the Agra fort or the introduction of vegetarian meals, these were significant markers for centuries to come, enabling a tiny Muslim minority to rule the non-Muslim majority. But the film fails to handle this momentous phase of history appropriately and instead churns out a masala mix that, despite the massive budget, results in mediocre film-making.

Jodhaa-Akbar attempts to capture the essence of that particular moment: the Indianisaton of the Mughal court and most importantly, the royal household. Whether it is to do with the grafting of a temple within the Agra fort or the introduction of vegetarian meals, these were significant markers for centuries to come, enabling a tiny Muslim minority to rule the non-Muslim majority. But the film fails to handle this momentous phase of history appropriately and instead churns out a masala mix that, despite the massive budget, results in mediocre film-making.

This is not to say that the film is without merit. It is visually stunning in places and A R Rehman’s music is outstanding. The two stars Ashwariya Rai and Hrithik Roshan provide glamour and unreal beauty. The settings are competently improvised and yes, the feel of the whole cinematic experience does convey the cliched Mughal aura of splendour, excess and a hybrid aesthetic. Rai and Roshan exude that enigmatic chemistry which makes them an attractive pair on screen.

But it is the treatment of the subject, characters and nuances that disappoints, especially when one remembers director/producer Ashutosh Gowariker’s earthy and under-your-skin rendition in Swades . In the pursuit of commercial success, Ashutosh relies on soft plagiarism. The battle scenes remind one of the Hollywood blockbuster Troy; the inanimate army contingents resemble those in Gladiator; and the sword fighting sequences re-enact the visual tricks of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon . But these are all still pardonable.

The most unforgivable moment in the film is the near destruction of an otherwise lilting melody, Khawaja Meray Khawaja , meant to be an incantation for the great Hazrat Khawaja Moinuddin Chishti buried in Ajmer. The filming of this song is almost farcical. The Qawwals aiming at Sema end up mimicking the whirling dervishes of Konya. To add insult to injury, they also wear Rumi caps and sport fake beards. At the end, our secular Emperor joins in the whirling of the dervishes. Understandably, this was a purely commercial gimmick. However, the mystic haal (trance) of the South Asian variety is distinctive for its myriad forms and general lack of structure. Even if this sequence had to be used, there could have been better ways of employing the global hit whirling stunt.

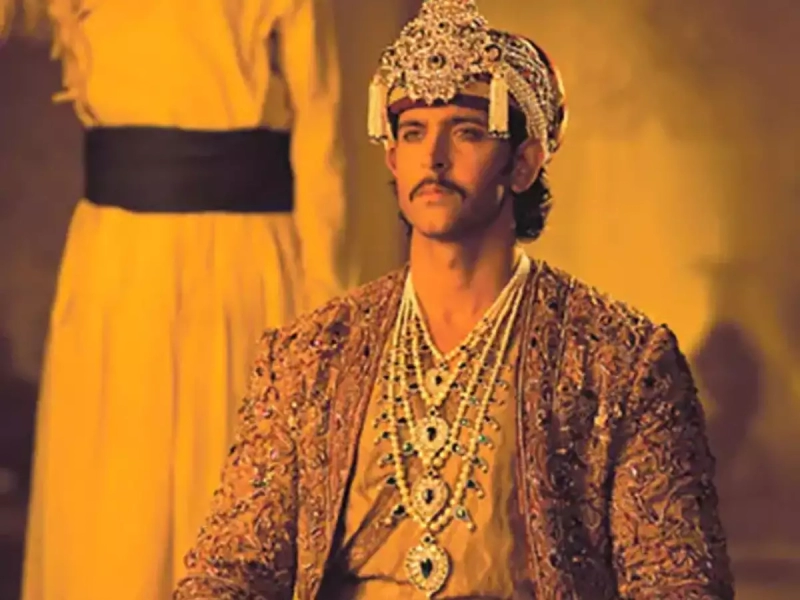

Another minor anecdote overlooked by Gowariker and his co-writer Haidar Ali is that Akbar sought blessings from Khawaja Moinuddin Chishti by walking barefoot to his shrine rather than tying his nuptial knot at the shrine (image above shows Akbar at the shrine). Talking of facts, it is also unclear who Jodha Bai was. Yes there are Jodha’s quarters in each of the Mughal palaces, but the Rajput princess whom Akbar married, according to some versions, was Harka Bai, daughter of the ruler of Amber, Raja Bharmal. To be fair, there are several disclaimers in the titles so one can overlook this license with history taken by the director.

What is sad is that the script props cardboard characters and insists that they are larger than life. Not much is known of the relationship between Akbar’s powerful foster mother Dai Anga and Jodha Bai. But the characterisation in the film turns into a mocking recreation of Kyunki Saas bhi Kabhi Bahu thi ethos with domestic struggles taking place on who controls the kitchen and what food is to be cooked for the Emperor. The handling of this conflict in the film reeks of those infamous STAR Plus serials hugely popular in India. If at all, this conflict was about power as the Rajput Empress (like the later Queen Nur Jehan) inducted her kith and kin in senior positions within the Empire. That Dai Anga was a female power centre at the Mughal court is glossed over. And, what can one say about the poor Nau Ratans — the famous nine advisers of Akbar as they appear such caricatures and lifeless beings on screen. Admittedly, the film was not about Akbar’s court; however, this does not mean that the larger setting of this love story should have been treated with such an amateur brush.

One fails to understand why the honour-obsessed Rajputs in India are protesting. If anyone needs to protest it should be the Muslims of the subcontinent. Except for Akbar and his Persian mother, Hameeda Banu Begum, the film unwittingly promotes the Muslim stereotyping agenda. From Bairam Khan to Akbar’s brother-in-law, almost every Muslim is barbaric, intolerant and, more often than not, scheming. The Mughal characters were complex people, neither barbaric Mongols nor Kabir chanting Bhagats. Ancient and medieval Indian history is replete with tales of violent Hindu rulers, so what differentiates them from the Mughals? From a subaltern point of view the local populace underwent a discontinued experience of exploitation. Akbar’s humanism and tolerance was unprecedented in that age. The film harps on these themes for a particular message but ends up validating all that the Hindutva brigade loves to say, and is never afraid to say, about Muslims and Muslim rulers in particular.

The performances are perfunctory except for the leading protagonists. Both Roshan and Rai come across as fairly fluid actors and for once do not massacre common Urdu words such as Khoob and Khush . The cinematography is first rate and the costumes (including the jewelry) are aesthetically noteworthy. Alas the script and its structure, is what undermines the entire effort. Bollywood may have surpassed world cinema in technique and viewership but it lacks that elusive attribute known as quality-screenplay not to mention its total disregard for time in true South Asian fashion. For instance, Jodhaa-Akbar at times appears to be a real time drama. The total length of the film is three and a half hours. Was there an editor on the team?

Having said that, it is a fairly watchable film as it tries to re-invoke the medieval process of Hindu-Muslim co-existence; and brings a lost era back to life. Jodhaa-Akbar also, rather boldly, depicts the unusual cinematic tale of a Hindu woman falling for a Muslim man, albeit grounded in political opportunism. Rajput honour protests against the film in India need to be understood in this light. For once Bollywood has undone the cliche of Muslim woman and Hindu man.

Those interested in the Mughals should see this film preferably on a big screen. Jodhaa-Akbar could have been a great film. Its main theme held that intrinsic potential but it was splintered by an overdose of pop history, a flaky script and the relentless commercialism that defines our age.

First published in The Friday Times, Pakistan