The subcontinent during the 15th century witnessed the coming of age of a process that started brewing with the arrival of Central Asian Sufis, those eternal travellers who arrived in India with a message of Islam and mystic love. When Sufi thought, an off-shore spiritual undercurrent to the rise of Islam, met its local hosts, the results were terrific. There was no shortage of fundamentalists and communalists in that cultural landscape; and the gulf between alien rulers and the native subjects was a stark reality as well.

Nevertheless, a synthesis of sorts was navigated by hundreds of yogis, Sufis and poets of South Asia. Very much a people’s movement from below, the Bhakti movement articulated a powerful vision of tolerance, amity and co-existence that remains relevant today. This is many centuries before the suave, Western-educated intelligentsia coined the ‘people-to-people’ contact campaigns. Yes, much has been lost in the tumultuous 20th century and perhaps these histories are irreversible. But a vast and complex common ground was nurtured by mystic poets of northern India, now comprising India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The powerful and soulful voices of Kabir, Bulleh Shah and Lalon Shah sing a shared tune: of love, and of rejection of formal identities based on caste, organised religion and class. In doing so, these mystics unleashed a process of interfaith dialogue and understanding, and the triumph of humanism even under the most adverse political and economic circumstances.

The powerful and soulful voices of Kabir, Bulleh Shah and Lalon Shah sing a shared tune: of love, and of rejection of formal identities based on caste, organised religion and class. In doing so, these mystics unleashed a process of interfaith dialogue and understanding, and the triumph of humanism even under the most adverse political and economic circumstances.

Their messages are similar in tone and tenor as if it was a thread, like Kabir’s weave or Bulleh’s dance or Lalon’s rustic songs that continues from the 15th to the 19th centuries, and even today. In this linear and non-linear time horizon, the messages of these poets have been embedded in popular culture, language, rural rites and everyday life.

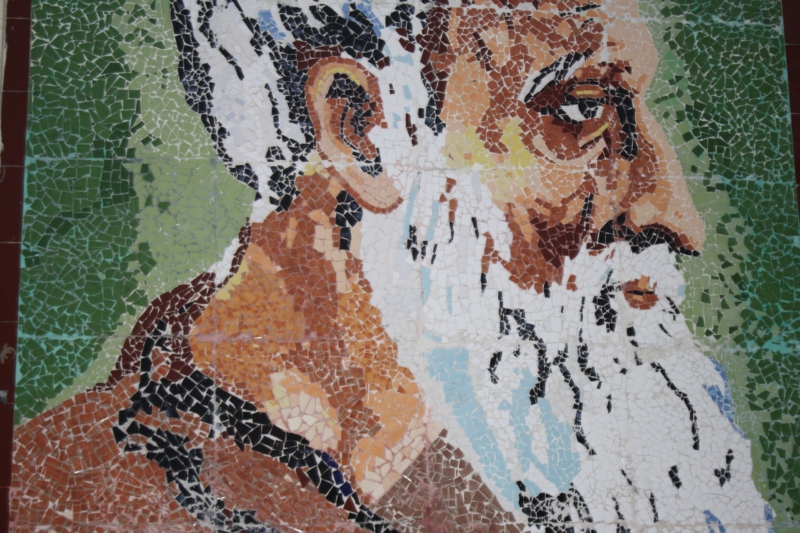

Kabir (1398-1448)

Kabir – born 71 years before Guru Nanak – is the most supreme, sublime and perhaps most simple of the voices from the Bhakti era. His poems have been sung across the subcontinent now for nearly five centuries. Researchers grappled with the challenge of sifting the original Kabir from all that is attributed to his name. Was he a Muslim or a Hindu? We know that there is more than one tomb where he is ostensibly buried.

A weaver by profession, and therefore at the lower end of socioeconomic strata, Kabir represented the woes of rural folk who lived in ‘thousands of villages’ at the margins of central power and its intrigues. Kabir’s songs were reformist in nature and influenced the ordinary villagers and low castes and provided them self-confidence to question Brahmins.

O servant, where dost thou seek Me?

Lo! I am beside thee.

I am neither in temple nor in mosque:

I am neither in Kaaba nor in Kailash:

Neither am I in rites and ceremonies, nor in Yoga and renunciation.

If thou art a true seeker, thou shalt at once see me:

thou shalt meet Me in a moment of time.

Kabir says, ‘O Sadhu! God is the breath of all breath’.

An eminent translator, Vinay Dharwadker, has explored the underlying secularism of Kabir’s verse by detecting the extra dimension far beyond known boundaries of secularism. He writes of how the Kabir poets and followers between the 16th and 18th centuries added to the discourse of spirituality and the primordial search for God. As Dharwadker writes, a God without attributes, or the Nirguna God that lies outside the scope of the ‘religious’, makes the concept of God essentially secular.

Dharwadker’s translation of a Kabir poem entitled Allah and Rama sums up the Kabir-vision :

Bulleh Shah of Kasur, in Central Punjab, is another towering voice that provided a mystical message beyond caste, institutionalised religion and ideologies of power. Born in 1860 in a Syed family, he found a Murshid (spiritual master) in Shah Inayat who was an Arain (a lower caste). This enraged his family and they almost disowned him. However, intoxicated with the love for his master and driven by ideas of unity of existence and equality of humans, he rejected such notions and stuck to his humanism.

Bulleh’s poetry reflects his rejection of the orthodox hold of mullahs over Islam, the nexus between the clergy and the rulers and all the trappings of formal religion that created a gulf between man and his Creator. A common theme of his poetry is the pursuit of self-knowledge that is essential for the mystical union with the Beloved.

yes, yes, you have read thousands of booksbut you have never tried to read your own selfyou rush in, into your Mandirs, into your Mosques but you have never tried to enter your own heart futile are all your battles with Satan for you have never tried to fight your own desires

Bulleh Shah’s murshid, Shah Inayat, belonged to the Qadriyya Shattari School, known for its close affinity with yoga and other meditative practices. On the limitations of organised rituals, Bulleh Shah’s said: Demolish the Mosque, demolish down the temple Demolish down everything in sight. But don’t (demolish) break a human heartSince that is where the Almighty lives

The yearning for anonymity and connecting with the Beloved requires that there are no distractions, no castes and no illusions of attachment. Bulleh Shah’s verse and its translation say this directly and passionately. His famous Kaafi, Ik nuktay wich Gal mukdee aye , is a culmination of all that he imbibed from the Bhakti inspired milieu of the subcontinent and the people’s everyday beliefs and coexistence at the subaltern level. As Muzzaffar Ghaffar translates: Catch the point, drop the academePush away divisions which blaspheme. Cast off hell, the grave, chastisement extreme. Cleanse out the heart’s every dreamInto this house everything descends

Love all people and you will reach your

Krishna or your Allah.

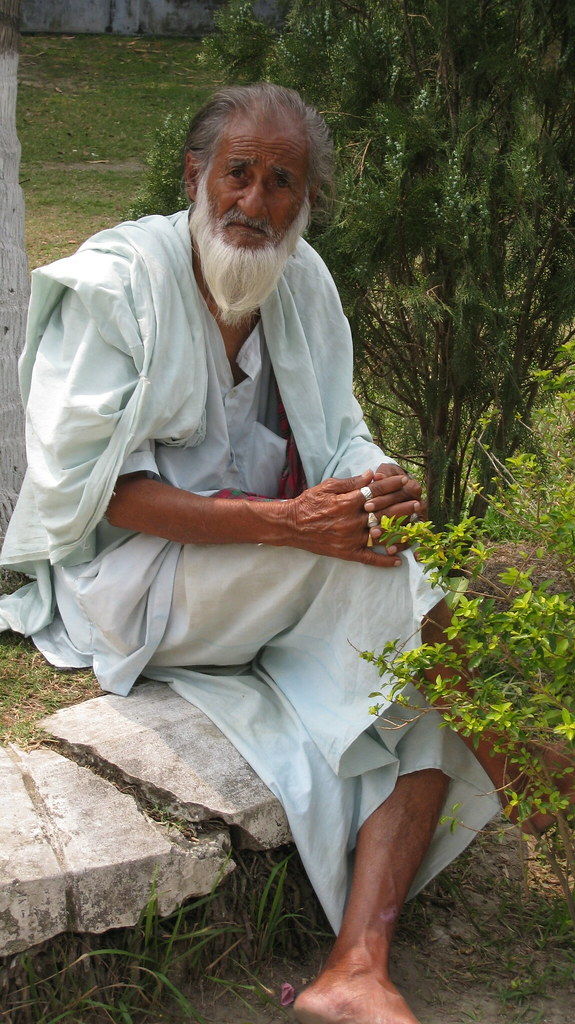

If the Western and Central parts of India were fragrant with the songs of Kabir and Bulleh Shah and many others of their ilk, the Bauls of Bengal were challenging orthodoxies in the golden climes of rural Bengal. Rabindranath Tagore introduced the world to the mystic songs of Lalon Shah. The Baul thought processes and music also found way into Tagore’s creative vision.

The mystical cult of Bauls (a community of low-class, illiterate, wandering singers whose wisdom is not based on formal schooling, but emanates from a ‘lived’ contact with an intensely lived life and nature) emphasise a peculiar spiritual discipline that brings together the animistic past and the organised religions of Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam.

Lalon, the best known Baul, has articulated thoughts akin to Sufism calling for the purity of soul and emphasis on humanism. Like Kabir, Lalon’s origins are contested. Some say that he was a Hindu by birth and raised in a Muslim household. According to one tradition, while travelling as a young child, Lalon contracted smallpox and was so unwell that his companions gave him up for dead and abandoned him. Fate took him to a nearby village, where a Muslim family of a weaver community saved him and nurtured him to health. Another tradition records that a farmer namely Malam found a near-dead Lalon on the bank of the Kaliganga river, between earth and water, and brought him back to life.

This survival between soil and water has taken a profound and symbolic meaning for Lalon’s followers. Thus, his birth is both known and unknown – between water, mud and close to death, and yet Lalon lived on.

When Lalon returned to his village after his recovery, he was castigated by his own community for cohabiting with a Muslim family. This was the turning point in Lalon’s life. He went back to the Muslim family, who later became his disciples. Matijan, Malam’s wife, is buried next to him as per his wish; he wanted the tomb to be known as Lalon-Matijan tomb.

In life and in death, and like Kabir and Bulleh Shah, Lalon shunned all distinctions of caste and creed. His poem entitled Casteism, translated by Azfar Hussain says it all :

People ask, what is Lalon’s caste?

Lalon says, my eyes fail to detect

The signs of caste. Don’t you see that

Some wear garlands, some rosaries

Around the neck? But does it make any

Difference brother? O, tell me,

What mark does one carry when

One is born, or when one dies?

A muslim is marked by the sign

Of circumcision; but how should

You mark a woman? If a Brahmin male

Is known by the thread he wears,

How is a woman known? People of the world,

O brother, talk of marks and signs,

But Lalon says: I have only dissolved

The raft of signs, the marks of caste

In the deluge of the One!

It is believed that Lalon died at the age of 116 years, after singing songs throughout the night. Hindus claimed Lalon as their own, as did Muslims; but Lalon knew that birth histories lead to politics of identity, and never disclosed his origins. He even chose the name ‘Lalon’, which could be of any community and of either gender.

Kabir, Bulleh Shah and Lalon are petals of a mystic lotus that blossomed in medieval India imbibing the ancient and the contemporary and has become the language of the people. The Punjabis across India and Pakistan are united by the kaafis of Bulleh Shah and the Bengalis sing Lalon songs across historical divides. And Kabir and his hundreds of personas permeate our language, ethos and cultural attitudes not in those palaces and power mongering lanes that perpetrate violence, or the seminaries of organised religion that preach ignorance, but in hearts and everyday lives.

Published in the Weekly Friday Times July 24 issue

This article is based on the longer paper published in the Third Frame, a quarterly journal of the Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi