The cancer of communalism and bigotry in South Asia continues to haunt us. These days, the Muslims are once again a subject of intense, though not always fair, scrutiny in India: their loyalties are being questioned and many are potential terrorists if not already abettors of violence. The post 9/11 world has contributed to the demonising of the Muslim identity and history to surreal heights.

The recent bomb blasts in Delhi have placed the communal discourse on the front pages. The invaders and violent Muslims have done it again. A friend called me from Delhi and narrated the profiling that takes place at marketplaces and how the gulf between different communities is widening.

There was a time, not in the ancient past, when in Delhi the greatest of Urdu poets Mirza Ghalib (1796-1869) lived in an age when Hindus and Muslims shared common saints, dargahs and even popular gods and goddesses. Written accounts of this age – the mid to late 19th century – relate how intimate co-exitence of ‘Mussalmans’ and ‘Hindoos’ had led to a relative amalgamation of customs among the common people. And poets like Ghalib could see the commonalities of spiritual streams:

In the Kaaba I will play the shankh (conch shell)

In the temple I have draped the ahraam (Muslim robe)

The verse above delineates the Sufi concept of fana (or dissolution of the self in divine reality) and the unity articulated by the ancient Indian texts such as the Vedanta. Sufis were to elaborate this as the wahdat-al-wajood (Unity of Being) philosophy.

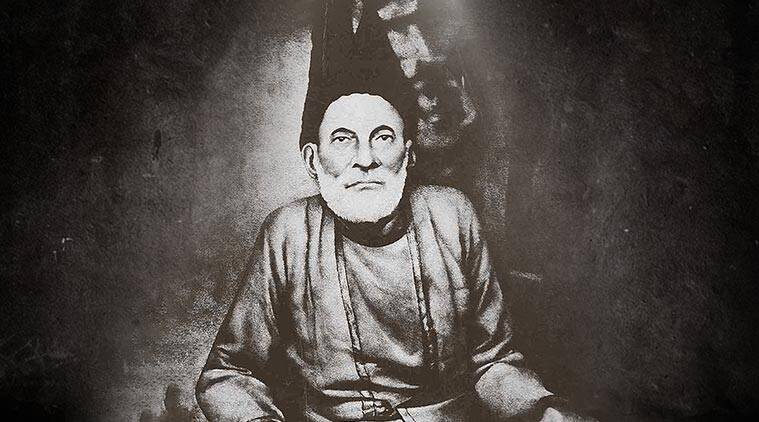

Ghalib’s vision of a secular man and society were therefore largely shaped by the crystallisation of a centuries’ long evolution of co-existence, of a culture that was inclusive and beyond the rigidities imposed by clergies. When still in his teens, Ghalib moved to Delhi from Agra. A proud descendant of Turkish ancestors, Ghalib was a phenomenal mind and a poet gifted with boundless imagination. Through his life he suffered financial insecurities that made him look for patronage first at the Mughal Court and later from the British Government. However, his poetic imagination blossomed and his mastery over the craft and soul of Urdu ghazal is universally acknowledged.

Persian is no longer an accessible language for most readers in India and Pakistan. Ghalib was proud of his Persian verse. This is why the discovery of a lesser known Persian mathnavi (a long rhymed poem), Chiragh-e-Dair (the temple lamp), has left me amazed at the range of his vision and the integrity of his intellect. Ghalib’s modern Indian biographer, Pavan Varma, has produced a competent English translation of this Persian mathnavi in Ghalib: the Man and the Times . Translations never do justice to the originals, but the grandeur of Ghalib’s thought process has not been lost in this translation.

May Heaven keep the grandeur of Benaras

Arbour of this meadow of joy;

For oft returning souls – their journey’s end.

In this weary Temple land of the world,

Safe from the whirlwind of Time,

Benaras is forever Spring.

This poem was written when Ghalib broke his journey to Calcutta at Benaras. Benaras, or Varanasi, is a revered site in Hinduism, believed to be where time originated. Varanasi is also sacred in the Buddhist scriptures, as well as in the great Hindu epic of Mahabharata . Dotted with ancient temples and ghats , the embankments along the river Ganges have attracted millions of pilgrims for centuries. Ghalib’s journey to Calcutta was made with the intent to petition the British authorities for the resumption of his royal pension, which had ended with the Mughal rule in India. Ghalib resided in Benaras for a month or so and imbibed the temporal and spiritual beauties of this ancient city.

The masnavi in a symbolic way cites Kashi as Kaabaa-e-Hindustan, something that clerics in India and Pakistan would not tolerate in the 21st century.

The Kaaba of Hind;

This conch blowers dell;

Its icons and idols are made of the Light,

That once flashed on Mount Sinai.

These radiant idolations naids,

Set the pious Brahmins afire, when their faces glow

Like moving lamps…on the Ganges banks.

It is incredible that a Muslim poet who prided himself on his Turkic ancestry and invoked the ‘warrior’ past in his day-to-day conversation (through his letters) could compare the divine light at Mount Sinai to the lamps at Benaras

It is incredible that a Muslim poet who prided himself on his Turkic ancestry and invoked the ‘warrior’ past in his day-to-day conversation (through his letters) could compare the divine light at Mount Sinai to the lamps at Benaras. This is a poem of extraordinary beauty, of cultural grace that romanticises Ganga (Ganges River), Kashi (another name for Benaras) and their magnificence through a unique set of images:

Morning and Moonrise,

My lady Kashi,

Picks up the Ganga mirror

To see her gracious beauty,

Glimmer and shine.

Later in the mathnavi, the poet questions a ‘pristine seer’ who knows the ‘secrets’ of whirling time: “Sir, you will perceive/ That goodness and faith, fidelity and love/Have all departed from the sorry land/Brother fights brother./Unity and federation are undermined./ Despite these ominous signs/ Why has doomsday not come?”

The seer rather poignantly points towards Kashi and smiling gently tells the restive poet that the ‘Architect’, is fond of Kashi’s edifice that is the source of all colour in life; and He would not like it to ‘perish and fall’. And the pride of Benaras soars to an eminence, ‘untouched by the wings of thought’. This was not the first or the last poem to be inspired by the ambiance of Benaras but for a Muslim poet to compose it was phenomenal. I wonder if today such lyricism and cultural inclusiveness is even remotely achievable by any poet of the subcontinent.

Admittedly Ghalib’s unconventional views were not fully shared by many Muslims. However, if there was lack of tolerance, it would have been impossible for Ghalib to loudly proclaim his views and retain the immense following in Delhi and outside.

Pavan Varma, the translator and biographer, further tells us: “In a time of fundamental discordance with his views, it may not have been possible for a Hindu, Munshi Hargopal Tufta to become Ghalib’ foremost Shagird [pupil] and closest friend. Not would it have been possible for Ghalib to declare another Hindu – Shivji Ram Brahman – to be like a son to him; or for the Mughal emperor of his age, Bahadur Shah Zafar, to appoint a Hindu convert to Christianity – Dr. Chaman Lal as his personal physician”.

Such times can only be imagined like the long-lost tales from a Never-never-land. This is an age of terror, profiling and fracturing of what was created by a millennium of cultural accords and understanding.

And there is no Ghalib to inspire and reclaim the music of human coexistence.