Ten years ago, on a grey, brutal January day, the great artist, Akhlaq, and his gifted daughter, Jahanara were shot dead…the innate humanism of Akhlaq and his family was shattered to bits, much like the splintered state of Pakistan, where art and life are either marginalised, silenced or blown to pieces

It is not easy to write about Zahoor ul Akhlaq (1941-1999), an artist whose life and work in so many ways encapsulates the troubled soul of Pakistan. Ten years ago, on a grey, brutal January day, the great artist Akhlaq and his gifted daughter, Jahanara, were shot dead. This was not a run-of-the-mill incident. The innate humanism of Akhlaq and his family was shattered to bits, much like the splintered state of Pakistan, where art and life are either marginalised, silenced or blown to pieces.On this January afternoon, Shahbaz Butt, an acquaintance of Pappu Sain, shot Jahanara and her fiancè, Al-Noor. Jahanara, 24 years old at the time, fell on the ground, to die. The noise, alarming Akhlaq and his fellow artist Anwar Saeed, sent them rushing in to see what had happened. Anwar Saeed was injured by Shahbaz, who shot Akhlaq. He died on the spot..Shahbaz now languishes in jail, while Pakistan is deprived of two inimitable souls. It is unclear what prompted Shahbaz to wreak this senseless violence: drugs, inability to cope with life or an extreme sense of inadequacy that could only be corrected through violence.

It is not easy to write about Zahoor ul Akhlaq (1941-1999), an artist whose life and work in so many ways encapsulates the troubled soul of Pakistan. Ten years ago, on a grey, brutal January day, the great artist Akhlaq and his gifted daughter, Jahanara, were shot dead. This was not a run-of-the-mill incident. The innate humanism of Akhlaq and his family was shattered to bits, much like the splintered state of Pakistan, where art and life are either marginalised, silenced or blown to pieces.On this January afternoon, Shahbaz Butt, an acquaintance of Pappu Sain, shot Jahanara and her fiancè, Al-Noor. Jahanara, 24 years old at the time, fell on the ground, to die. The noise, alarming Akhlaq and his fellow artist Anwar Saeed, sent them rushing in to see what had happened. Anwar Saeed was injured by Shahbaz, who shot Akhlaq. He died on the spot..Shahbaz now languishes in jail, while Pakistan is deprived of two inimitable souls. It is unclear what prompted Shahbaz to wreak this senseless violence: drugs, inability to cope with life or an extreme sense of inadequacy that could only be corrected through violence.

A decade later, Akhlaq’s immense legacy is all but invisible, thus marking a post-death demise. How and when did we come to such a pass? This is what the conspiracy of circumstance and the context of Pakistan have done. “The single most important influence on contemporary Pakistani art”, in the words of Salima Hashmi, renowned artist and Akhlaq’s close associate, is absent from art discourse. It is this apathy that I wish to remember on his tenth death anniversary, along with the infinite spaces that his art nurtured and created for generations to come.

As an avid student of Pakistan’s avante garde modernist, Shakir Ali, Akhlaq was destined to radicalise the sensibilities of art movements and pedagogy at Lahore’s famous National College of the Arts (NCA). The young artist, Akhlaq, had the good fortune to live in Shakir Ali’s home in Lahore’s Garden Town suburb for quite some time, and this is where he imbibed the iconoclasm and poetry of Ali’s work and continued the experimentation right into the mainstream of art education. Akhlaq’s early work bears testimony to the influences of the newly emerging school of modernism shaped by the visions of Shamza, Ali Imam, Ahmad Pervaiz, Moyene Najmi and others.

For this writer it was a gargantuan challenge to recount his legacy and re-discover him. Walking into the room where Akhlaq and Jahanara were ruthlessly murdered gave rise to mixed feelings. Akhlaq’s wife, the eclectic potter-artist Sheherezade has been struggling to deal with a life permanently altered on that fateful day of January 1999. The house, painted in bright colours, displays the vibrant world that Sheherezade has created; memory mixed with longing, recreating Jahanara’s dance, using colours from Zahoor’s palette for embellishment.

As we commenced our conversation, we soon found ourselves lost. The little corners of silence between sentences were filled with the mysteries of Akhlaq that still remain undiscovered, at least in large measure. Sheherezade told me about his journeys from Delhi to Karachi in the forties and eventually to the NCA in the sixties, where he found his voice. In 1966, Zahoor was awarded a British Council Scholarship and joined the Hornsey College of Art, to be followed by a stint at the Royal College of Art. This is where the interaction with the British Museum and its priceless, tragic collection of Mughal miniatures opened new vistas for Akhlaq. Once back in Pakistan, he started to imbibe the miniature forms, spaces and poetries into his style, as well as setting up the miniature department at the NCA.

As an exuberant and bohemian student, this was the time when Sheherezade met Akhlaq, found herself under his spell and defied her family to marry him at the Karachi flat of Shahid Sajjad, the eminent sculptor. Jamil Naqsh was also there and the group of friends had a long, fun-filled day on the shores of the salty Arabian Sea. Sheherezade had a glint in her eye as she narrated the event before she remarked: “Zahoor was the first and perhaps the last interesting, ah the most interesting, person I have ever met. I have never found anyone as enchanting as him”.

Akhlaq was a man of few words, another trait he might have inherited from Shakir Ali. Space, silences and reflection defined much of his time. This is not to say that he was not sociable. His closest friends were at the NCA, with whom he spent a fun-filled time when he was not delving into philosophy, or creating his masterpieces in states of frenzy, intoxication or exceptional lucidity.

Sheherezade further mused how the NCA and Zahoor developed a symbiotic relationship that was mutually transformational. Akhlaq was a “peculiar and an unusual husband, but he enabled me to develop a parallel life and thus expanded my life-experience”. Like his other relationships, the marital partnership was also intense yet parallel to his inner life. Zahoor needed a lot of space, ‘the space of night’ in the words of his biographer, and sometimes he did not get it. It was one of those extraordinary experiences that entail a life of one’s own.

Added to this was Zahoor’s immense knowledge, spanning subjects as varied as art, history, philosophy and calligraphy, a discipline in which received training from an early age from the renowned calligrapher, Yousaf Dehlavi. His appreciation of the skill and intimacy with discipline therefore were passed on to him in his childhood. Behind the screen of tradition, and going back to the roots, was also the classic scar of migration and uprooting. Akhlaq’s family left their beloved Delhi for Karachi at the gruesome moment of Partition in 1947. The nostalgia and the sense of separation which underlies Akhlaq’s work were pervasive. Later, his various travels to different parts of the world intensified both the rootedness and the contemporaneousness in his work.

Such profound influences – of heritage, training, travel and intense relationships – enabled Akhlaq’s work to straddle both the traditional and the contemporary, encompassing visual traditions that represented as well as defied the geographical and political boundaries of Pakistan. Akhlaq could concurrently weave the discipline of Islamic geometry, the iconography of the Mughal manuscript, the well-worn genres of European painting and Pakistan’s colonial heritage all into one space, and yet there was space left over to express the contemporary artist of today. There is not a single moment when his work is bound by the constraints of the past or the woes of the present; there was synthesis, a fluid one, merging the thousand years of Pakistan’s heritage onto speaking canvases. Rashid Rana, the young artist of global recognition and an avid student of Akhlaq narrated how the latter helped his generation liberate itself from the onerous baggage of tradition by reinventing ‘tradition’ itself.

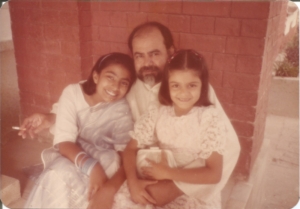

Along the fascinating journey of Akhlaq’s creativity, the two daughters of the couple, Jahanara and Nur Jehan, help deepen that quest for equilibrium, the synthesis of the old and the new; of creativity and the institution of marriage. Concurrently, Akhlaq’s genius flourished as an outstanding sculptor, printmaker and painter, and he received multiple awards within Pakistan and abroad. By the 1980s, he was criss-crossing disciplines and art forms, thus delving deeper into Islamic art, painting, printmaking and sculpture. In 1989, Akhlaq joined Yale University, USA, to pursue post-doctoral research at its Institute of Sacred Music, Religion and the Arts. After retiring from NCA as the head of the Fine Arts Department in 1991, Akhlaq proceeded to Bilkent University, Ankara, as a visiting professor, and by the mid nineties, the family had landed in Canada. Here, Akhlaq received an appointment at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. The return to Pakistan in the late 1990s was the finest of hours, when he had acquired the status of a guru of sorts. But the apex of Akhlaq’s artistic, cultural and philosophical abilities was truncated, and left a trail of blood on Pakistan’s conscience. And, it was not only his. With him, Jahanara, a passionate Kathak performer, the symbol of Akhlaq and Sheherezade’s commitment to lead a life of creative spaces and non-conformity, was also murdered.

The tragic irony of these murders, in the cruel, ugly daylight of a messy society, was a result of Jahanara’s foray into Sufi music played at the shrines, and in her pursuit of humanist moorings. Her’s was an eclectic upbringing that emphasised unpacking class and status and finding oneness with music. How bitterly was that dawn prevented from turning into daylight.

Ten years later we grapple with the question raised by a student of Akhlaq, Quddus Mirza, who is both an artist and an art-critic. Mirza said rhetorically that Akhlaq had died again, in the erosion of his pivotal influence on the Pakistani art scene and especially from strands of art education.

Salima Hashmi agreed with the unfortunate trend, but said that Akhlaq’s legacy lives in the form of Pakistan’s best artists today. While elaborating on this, she mentioned Quddus Mirza, Naazish Ata-ullah, Ali Raza, Shazia Sikander, Rashid Rana and Imran Qureshi. If anything, since her assumption of the office of the Principal of NCA, Naazish Ata-ullah has revived many of Akhlaq’s teaching methods that involve interaction between students and faculty, and other innovations that made art-education step beyond the limits of formal instruction and enter the nebulous domain of the self.

In fact, Ata-ullah is emphatic in stating that Akhlaq was the best teacher she ever encountered; and recalls the relationship that he nurtured between art, rootedness and the self. He constantly sought feedback on his work and encouraged discussions that took art practice beyond studios and classroom – straight into the threads of living.

Hashmi, however laments that most of Akhlaq’s works are abroad in private collections of the West and not much is available for students and teachers to view. A relationship with art can only be established through ‘intimate interaction with the canvas’, and the blank spaces of art galleries, including the National Art Gallery in Islamabad testify to the way many forces have rendered Akhlaq invisible. In fact, there is hardly anything available in the public domain and whatever is found, is limited and unrepresentative. The NCA art gallery was named after Akhlaq and this was one of the last things that Salima Hashmi accomplished at the end of her tenure as Principal.

Sheherezade recounted the lobbying she has been doing to make Akhlaq visible again, since there is much that needs to be explored from the gamut of his larger than life persona and his treasure of scattered works. Sheherezade has been active in documenting, preserving and exhibiting Akhlaq’s work under her organisation called Laal. A small and beautiful book was also published by Laal on the artist, though it is another matter that this small red-dotted volume ‘is not even found in most Pakistani libraries’, said Sheherezade. “Today’s younger art practitioners and students are barely familiar with Akhlaq, and even the students at the Indus Valley School of Art, whose logo was designed by Akhlaq, have little idea of who the brand creator was!”

We as a society excel at tottering on the shores of forgetfulness; and as a state we are constantly in denial, quick in erasing history lest it haunt us and ask unsettling questions. The National Art Gallery in Islamabad, built after decades of inaction, needs to reclaim Akhlaq’s work and bring it back to Pakistan

We as a society excel at tottering on the shores of forgetfulness; and as a state we are constantly in denial, quick in erasing history lest it haunt us and ask unsettling questions. The National Art Gallery in Islamabad, built after decades of inaction, needs to reclaim Akhlaq’s work and bring it back to Pakistan. The ‘natural resting place’ to use Salima Hashmi’s expression, for Akhlaq’s oeuvre, is the National Gallery, and the government has to make a concerted effort to effect this homecoming. As I write these lines, I am also disturbed at what the National Gallery has become. Currently, it is hosting fashion shows and screening feature films. Someone has to take notice of this regrettable situation.

We have to begin somewhere. As Roger Connah who is writing a book on Akhlaq, informs me, the artist Anwar Saeed, who was also shot on that cruel day, had remarked that “no one person at present appears able to understand it [Akhlaq’s work] or structure it from a wider, detached view”. Well, how could that interaction with Akhlaq’s art and its wider appreciation start, when his works are not here and we are so involved in the act of forgetting. Connah has completed the manuscript entitled Exiles and Danced Furies: Zahoor ul Akhlaq, Art and Society in Pakistan that is due for publication in 2009. It will surely unpack his artistic life and its legacy.

At his tenth anniversary, on a frosty January evening, Sheherzade with Akhlaq’s friends, lights candles and lamps at her neo-mystical home on Lahore’s serene Scotch Corner, and resolves that the year 2009 will be the start of rediscovering Zahoor ul Akhlaq. It is heartening to hear that Quddus Mirza is pursuing doctoral research on Akhlaq and a Master’s thesis on the artist is underway at the Beaconhouse National University. NCA plans to highlight and refocus Akhlaq’s major sculptures; and The Drawing Room, a new art gallery, will organise a series of exhibitions of his work in 2009 culminating in a major retrospective.

On this occasion, there were some moments of silence and of erudite reflection by Naazish Ata-ullah, Salima Hashmi and others stating that this is the beginning of a long celebration of Zahoor ul Akhlaq’s intricate life and extraordinary work. Amid trays of fresh roses, the dancing lamps flickered in agreement.

This piece was published in The Friday Times – January 23-30 issue