He was a man, take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again

(Hamlet, Shakespeare)

It is only when Asim has gone that one takes measure of the legacy he has left for his troubled and torn country. A decade long association was lost on the fateful day of January when we heard of his untimely exit from this world. For hours, I sat in my office, numb. Not that Asim’s suicide was a surprise, for he had warned us all many times of this inevitable denouement to his dramatic life.

Five years ago, when I wrote a piece on the Pakistani poet Mustafa Zaidi and the romance with nurturing a death wish, Asim wrote to me and said that I had no clue what this was all about. His words were: “loved and was deeply moved by your piece on Zaidi… saw so much of myself in his life story, hoping I don’t die unsung and on the fringes, and wondering why you of all people would have a death wish”. Asim had suffered and struggled with his inner demons with an intensity that most of us will never appreciate. This was the first time that I knew about the seriousness of his other side: a dialectical dark side to his otherwise cheerful, loving and warm persona. Asim cannot be mourned; he can only be celebrated. He would have hated the melodramatic statements that I am inclined to write in this remembrance.

Two of my dearest friends were close to Asim in a way that is difficult to understand. Nearly a decade ago I met Asim at Ali Dayan Hasan’s home in Karachi. I was passing through on one of my occupational breaks from my assignment in Kosovo. Ali had returned from England and joined the monthly Herald and was piecing his life together. I met this lean and quiet young man who had big, bright eyes and a unique smile. We did not talk much except for a small argument over something, perhaps about a book, but I could not help being thoroughly impressed with his viewpoint. Since then I have had a series of exchanges, verbal and electronic, in which Asim was always animated, off-beat and extremely gifted with words and ideas. No wonder his art work and many of his writings are a formidable legacy for us all.

Born into a regular upper middle class family, Asim Butt was always an exception. He was different, as he would tell me. Rejecting convention, tradition and the confines of societal expectations was therefore something that started way too early with Asim. To be fair, he did pursue a path chosen for him. He attended the Li Po Chun United World College where his gift for painting became polished, and at some level he had chartered his future course. There was some meandering: a degree in the first batch of B.Sc. in Social Sciences earned from the Lahore University of Management Sciences; and later an unfinished PhD in History from the University of California, Davis. He returned to Pakistan, wrote for the Herald and other publications, and finally enrolled himself at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture.Not surprisingly, Butt graduated with distinction in 2006.

Asim would always say that he completed his BSc, and his higher studies in the US against his will, simply to please his parents, who had the usual expectations from their son. However, it is the rigour of academic training that informed his understanding of the world. At Asim’s memorial in Karachi, his instructor at LUMS, Khurram Hussain, declared that he had never met a student like him, and he was surely the finest among his peers.

Asim’s early work indicates the trauma that lived within him. There were images ranging from the macabre to the bare details of an inner life, expanding yet tormented. Self-portraits and hints of the artist’s inner universe were subtly and sometimes jarringly represented on paper or canvas. However, there was something extraordinary about his lines and his vision that remained unalloyed by convention. Asim sketched and painted what he saw, whether it was compatible with the classical theory of art or not. There was more defiance in his defiance, and a greater stir than the shock one would undergo after viewing his works.

Asim was perennially dissatisfied with his output. He was a fierce critic, and scathing, most of the time, about his work. His wide-ranging reading and sharp understanding of art provided him with the analytical tools to assess his creativity. Yet, he was aware that creativity and analysis were not easy bedfellows. Thus he swung between moments of extreme lucidity and his bipolar state – in fact the two co-existed rather smoothly within him.

Our acquaintanceship grew due to Asim’s intense association with Arif Pervaiz, a dear friend in Karachi. There was a period when Asim stayed at Arif’s place and I always met him there and spent extended periods of time with him. I also met a wide circle of his friends. Asim had unwavering loyalties that time and everyday disagreements could not diminish. I loved the way he would describe his life, family, art, relationships – a narrative that was tragicomic, self-deprecating and melancholic. He would joke about his paranoia and check a couple of times during the evening if he was being paranoid or his comprehension was on the dot. This rare gift was charming.

We met a couple of times in Thailand too. I was attending a governance and policy training course and Asim was travelling with Arif. We walked around on the wide pavements of Bangkok amid a sea of humanity and traffic and discussed everything under the sun. Asim had been to Koh Sumai and that had inspired him. However, at the Bangkok zoo, of all symbols, the vulture travelled with him. This particular vision and motif of a vulture, disturbing as it was, appeared in his paintings in the following years. He was intrigued by my spiel on the way the vulture was used as a symbol of an amoral being by the eminent Urdu writer Bano Qudsia in her epic novel, Raja Gidhh. I think Asim went and devoured the book. His fascination was intense, and I could not help marvel at the way he internalised the most unusual of visual experiences.

But it was Asim’s venture into public art and his subsequent adoption of the Stuckist creed that turned him into a major figure at a relatively young age. Unlike his peers, he broke out of the studio and its sensibilities. His murals at the Abdullah Shah Ghazi shrine in Karachi were electric, and involved the transitional communities of beggars, prostitutes, and the dregs of society who had been rejected by convention. This is where Asim discovered many soul mates – ordinary, nameless people – and interacted with them. One evening I visited the place with him. He was given a warm reception and his acquaintances flocked around him. His empathy, his connection with the context, was impressive; there was a seamlessness in their relationships and there were no barriers. Smoothly traversing this classless milieu was a scene and experience that I will never forget. I was extremely fond of Asim, and his eccentricities, but that day I admired him and was awe-struck as I encountered a true humanist beyond the confines of an armchair. It was an exhilarating experience.

In his late 20s, Asim had set his direction as if his creativity led him towards a public discourse. In 2005, he started the Karachi Stuckists group. Later, the corpus of his public art grew and attracted attention from critics, the media and citizens. During the anti-Musharraf movement, the interactive ‘eject’ signs became a tool of resistance. After Benazir Bhutto’s tragic assassination, his public art called for peace, which led him to speak against the fascist mafias controlling Karachi. He was advised by Arif to be careful in what he aimed at, but he was undeterred. The demolition of the old Metropole Hotel also provided him with much needed inspiration and an arena for further engagement. There he was collecting and saving debris, painting on the walls soon to be demolished. The Stuckist’s call for re-modernism, for a regeneration of spiritual values in art and society was being practised in public view and in the full glare of the electronic media.

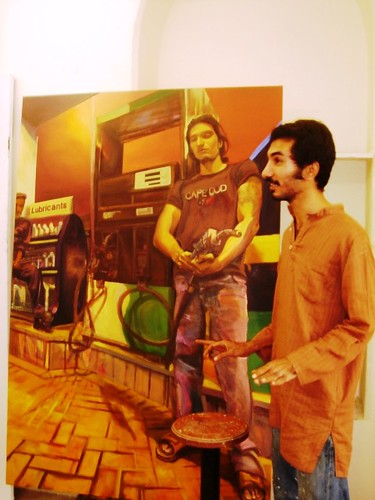

Asim’s restless spirit lacked a home however. He was not comfortable in structured settings and therefore he moved to different places during the last few years. Bhopal House, close to the Mohatta Palace (where Asim was banned for one of his three interactive pieces which sought to claim the museum as a lived space) became his abode for many months. Faiza S. Khan’s living quarters flourished as an art commune and Asim expressed himself on the walls, doors and quiet corners of this quaint property. I visited Asim in Bhopal House in late 2008. He wanted to show me his studio and the works under progress. He looked happy and settled, but this was just a mood swing. I posted a few pictures of him on my flicker collection, and Asim and I had a long argument on why I had chosen to caption one of the photographs as ‘the eclectic artist’. I gave in and changed the title since he was convinced that this was a negative description.

In 2009, Asim’s works were showcased at Khaas Gallery in Islamabad, his last grand exhibition, where a mature, evolved studio artist displayed his art. I could not attend the show but urged him to send me all the images. It took a while to commission a piece for TFT but it was published, and he approved of it. He did not know that I had to argue in-house to change the title description from ‘macabre artist’ to ‘extraordinary artist’. Asim’s paranoia was infectious.

Some time later, I discovered that he had moved out of Bhopal House and had gone back to his parents and then to his grandmother’s house. Few realised that Asim needed constant attention and monitoring of his medication. Sadly, the prescribed medication for depression was at odds with his artistic muse. He would lose interest in sketching and painting, and he therefore avoided medicine. It must have been a terrible choice, acutely aware as he was of the necessity of taking it to stabilise his bipolar disorder. But certain things remain outside our control and are best understood as the tragedy of the human condition.

Asim had been reading the drafts of my book and giving me his feedback. He even took time to suggest various titles. The book is not published yet, and Asim is no more. I will miss him once again. I never told him how his encouragement was a balm for my unsure self. I think of Asim’s parents, the concentric circles of friends especially those who had taken his unflinching love for granted, and those for whom he was a part of everyday existence. I know that asimicus@hotmail will be silent but Asim Butt will live on. His energy is imperishable and his memory indelible.

View the pdf version with photos – Asim Butt (1978-2010) as published by The Friday Times

Raza Rumi is a development professional and a writer based in Lahore. He blogs at www.razarumi.com and edits Pak Tea House and Lahorenama e-zines