The discourse on South Punjab conceals the grassroots social movements and the clamouring for a linguistic identity in the region

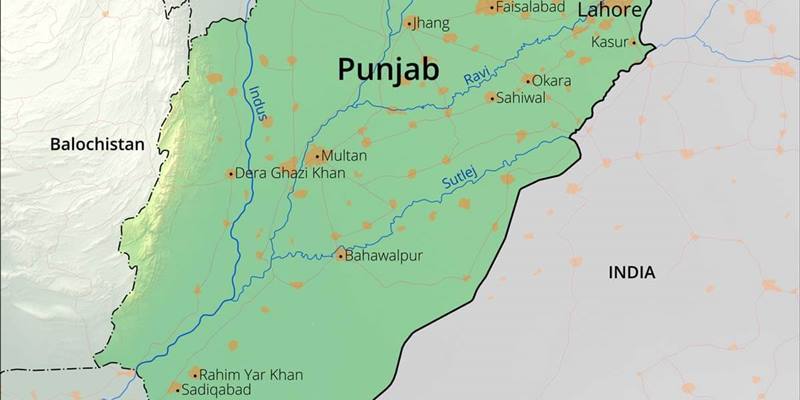

The conundrum of South Punjab remains a major challenge for analysts, policy makers and above all the people of this marginalized region. Socio-economic data testifies to the impoverishment and the deprivation that exists in the region. Add to this the iniquitous land distribution and utter lack of economic opportunities for the local population. Despite the rhetoric of the establishment, the region has been neglected through decades of “modern” development in northern and central Punjab. The bulk of public resources were invested in Lahore, Rawalpindi and other urban centers of the North. Industrialisation, growth of private education facilities and the rise of the middle class are phenomena that have eluded the dusty environs of South Punjab.

The result is clear: the electoral patterns show support for redistributive agendas and which are deemed as pro-peasantry. In recent years, southern Punjab has also witnessed two conflictual yet interrelated trends. First, the rise of Islamism through a network of sectarian madrassas which train militants and mercenaries alike; and scattered yet influential social movements around the issues of linguistic identity and livelihoods. How does one make sense of these contradictions?

It is well known that the Wahhabi-Salafi ideologies backed by potent financing networks have played a major role in turning this impoverished region into a nursery for militant Islamism that targets the plural Sufi culture embedded in the cultural mores of the local inhabitants; and act as a bastion for the Taliban network across the country. There is insurmountable evidence to this effect and those who are not willing to confront this brutal reality are living in a state of denial. Since the Zia years, the state is no longer a neutral arbiter and it promotes a particular brand of Islamic ideology. It is also clear that a sophisticated regime of economic incentives addresses lack of public entitlements and a non-responsive state apparatus.

However, we have also witnessed that the peasants in Okara and Khanewal have valiantly resisted appropriation of land by security agencies and have set a momentum of challenging the state’s land policy. Similarly, issues related to water distribution and resettlement due to mega projects sponsored by International Financial Institutions (IFIs), have also come into public light due to the political mobilization that has been taking place in D G Khan, Muzaffargarh, Layyah and elsewhere. It is a separate matter that such stories do not receive adequate attention in the media which is owned by rich, powerful barons whose interests are integrally linked to an extractive state. As pointed by a leading activist, Mushtaq Gadi, the discourse on South Punjab willfully ignores the authentic voices from the grassroots that revolve around livelihood struggles and the quest for a regional identity.

Another dimension of the regional turmoil pertains to the growing movement for linguistic identity. The Saraiki language and its submerged identity is now a rallying point for most living in the southern most districts of the region. This movement for cultural expression has gained momentum with increased calls for a separate province and the fact that the disputed status of Bahawalpur State has been raised by politicians from the region is a case in point. The state of affairs, reported rather cautiously in the mainstream media, points to the fact that political elites are now forced willy-nilly to subscribe to the idea of a separate province. Else, they are likely to be rejected at the next general elections.

In fact, the decades’ long denial of rights and entitlements and a politico-cultural identity act as great catalysts for breeding militancy. If one were to add the economic deprivation and endemic poverty to the list then the situation is quite alarming. No wonder we are seeing history unfold in front of our eyes. The nexus between poverty and militancy is problematic but certainly undeniable. FATA and other parts of Pakistan have shown us how a poor majority finds ‘opportunity’ in the game of terrorist networks and their well oiled financing machines. South Punjab is no exception.

Pakistani state will have to think beyond its mantras of national security and ‘foreign hand’ and accept that its policies have led to the explosive situation in South Punjab. At the same time, this region is not Swat or a FATA agency that can be bombarded with troops and drones. Also, it is important to note that at the people’s level, Talibanisation has yet to take root. There is hardly any evidence to suggest that there is popular support for the Taliban agenda. A relevant book entitled, Probing the Jihadi Mindset , Sohail Abbas (2007) that looks at the profiles of over 500 jihadis shows that participation of South Punjabis in the ‘Jihad project’ is minimal.

What next? First, major investments in public works and programmes that enhance employment and livelihoods in the region must be the focus of the state. Second, a comprehensive madrassa reform should take place concurrently that should quite logically start with the registration, documentation and curricula standardization. Third, networks that finance militancy should also be traced and tackled. The issue of a separate province or an autonomous region within the monolith Punjab province will need to be confronted sooner than later. Brushing it under the carpet will not help.

If the political elites have settled issues such as renaming NWFP, provincial autonomy and NFC then why can’t this issue be resolved within the democratic framework?

Raza Rumi is a development professional and a writer based in Lahore. He blogs at http://www.razarumi.com