The soulfulness of India’s greatest tragedienne was born of an abiding love for reading and writing.

Raza Rumi reviews a biography of the alluring star

Meena Kumari

Jisko Lagi Hai

Harper Collins have republished well known Indian editor, Vinod Mehta’s biography of Meena Kumari authored in the 1970s (Meena Kumari: The Classic Biography). This is a fine introduction to a larger-than-life person and performer. By no means authoritative it does give a fairly detailed account of her life, achievements and travails. As Mehta mentions at the start of the book, in 1972 he was a struggling ad copywriter “going nowhere. With false bravado which comes easily to a person who has achieved little, I accepted the commission and duly delivered the finished manuscript” in a few months. Mehta was “embarrassed at the effort” because the subject of his biography was not available for interviews, and Dharmendra – “the man who had callously used and discarded her” never gave him the time to hold detailed interviews. Having said that, the biography is fairly well-researched and brings forth lesser known facets of this exceptionally talented woman who remains a bit of an enigma to date.

Born in 1932 to Master Ali Bux (who migrated from Bhera in Punjab province) and Iqbal Begum (a Bengali Christian who converted to marry Iqbal), Mahjabeen (Meena) was the second of three sisters. Meena Kumari started her career at the age of 4 when she became a vehicle to supplement the family income and was taken to the studios. She started as a child actor with Leather Face and soon she was in high demand. Her transformation as a heroine was therefore an organic feat. Prior to her work as a heroine, Meena Kumari starred in many mythological films during the pre-Independence days, mostly playing Hindu goddesses. Mehta tells us how “A Sunni Muslim, without even a rudimentary knowledge of Indian scriptures, conducted herself with such familiarity that people on the sets often mistook her for a Hindu girl. She was so perfect in these mythologicals that the early Meena became an essential feature of this genre.” By the 1940s she was charging Rs. 10,000 for a film and very soon her financial independence empowered her to make her own choices.

Her love for books and the written word was immense. Given her early start, she had no formal schooling but was fluent in many languages and a voracious reader. She had started composing poetry and in later years Kaifi Azmi acted as a mentor. This love for the letters also brought Gulzar and Meena together while she was still married to her only husband Kamal Amrohi.

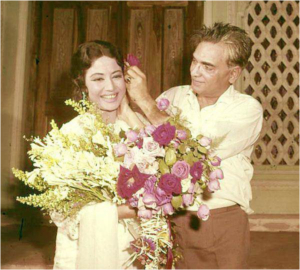

Mehta recalls how Meena while reading an English magazine was enchanted by a photograph of Kamal Amrohi. Kamal by then was a formidable name in Indian cinema after his excellent effort as writer-director for the classic Mahal. Events brought them close and for Meena Kumari this was the ideal match: an educted, refined and thinking man from the film industry. In Amrohi, Meena discovered “areas of gentleness, humanity and loyalty”. The two wrote letters to each other, spoke all night on the phone leading to their life-long insomnias. Meena defied her family and secretly married Amrohi. Being the prime income earner of the household, Meena was not to be married without appropriate financial calculation. This is why her father would have resisted the wedding, which he did indeed. Instead of relenting to his pressure, Meena left her house and walked into Amrohi’s apartment unannounced and started living there. This relationship lasted for over a decade.

The marriage, as we find out from Mehta’s book, became what all marriages turn into: a bitter contest of gender roles, failed expectations and looming suspicions (in this case Amrohi’s). The latter had imposed restrictions, among others, that no man could enter Meena’s make-up room in the studios. He had set timings for her to return home, etc. However, ‘our heroine’ as Mehta calls her affectionately throughout the book refused to comply with any of these restrictions. Eventually, she parted but not without a bit of real-life drama. Amrohi had tasked an assistant of his to remain close to Meena all the time. It was in the studios that Meena let the famous poet-writer and later director into her studio and made a public display of affection for him. The idea was to give Amrohi and his spies a clear message. Thereafter, she never returned home. And moved in with her sister and brother-in-law.

This personal drama was only matched by her dramatic success on the silver screen. The 1960s were the most prolific years for her. Stunning performances in films such as Parineeta, Dil Apna Aur Preet Parayi, Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam and Main Chup Rahungimade her the undisputed queen of those times, even more formidable than her rivals Madhubala and Nargis whose success was based on a mega hit or two. But ‘our heroine’ kept shining throughout in almost every genre of acting.

Mehta rightly points out that in “every frame of the film she fills the screen with her presence”, along with focusing on the great sex appeal that Meena exuded in the immortal song ‘Na jao saiyya chhuda ke baiya’ from the unforgettable Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam. An excerpt from Meena’s diary comes in handy for throwing a light on the great performance she gave in the film: “This woman (Chhoti Bahu) is troubling me a great deal. All day long – and a good part of the night – it is nothing else but Chhoti Bahu’s smiles, hopes, tribulations… Oh! I am sick of it!”

Meena acted as Chhoti Bahu when she was 32 years old and at the peak of her career. Chhoti Bahu was a character of a submissive Hindu Bengali wife clamouring for her philandering husband’s love and attention. The husband, a decadent zamindaar, remains unmoved by her efforts. To please him she starts drinking and ultimately finds some solace in another man. But the results are tragic. Meena’s real life intersected with this film as this was the time when she started to imbibe – starting with small doses of brandy turning into a full-scale addiction. Guru Dutt’s full use of Meena’s beauty and acting skills makes this character an unforgettable one. More so as it was off-beat, challenging the primacy of a suffering sati saavitiri of mainstream Bollywood’s imagination. At a deeper level, this was also a parable of changing social structures in a world unsure of the direction it was taking.

“Meena loathed ostentation and parties”

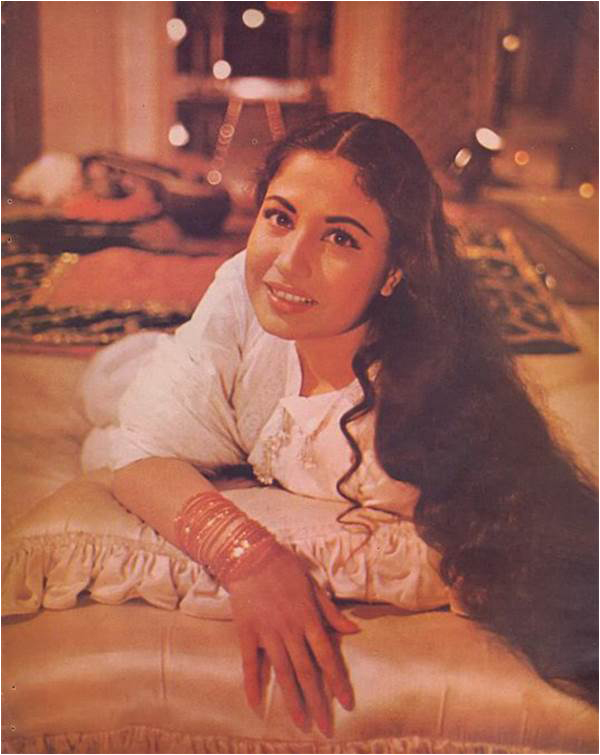

Mehta’s book also tells us about the signature white dress that Meena Kumari used to adorn in all her public appearances. Shabana Azmi reportedly told someone how she was struck by all things white in Meena’s house when she had gone to see her ostensibly at the behest of her father Kaifi saheb. I also recalled while reading Mehta’s book lines from A S Byatt’s novel Possession where the two characters Roland and Maud by some ‘powerful coincidence’ both pictured the ideal state of being as an empty, clean, white bed. This fetish for white needs a separate essay but there is in Byatt’s words the possibility of exploring and celebrating ‘companionable silence’ through white. Mehta also states that Meena loathed ostentation and parties and “the synthetic bonhomie of the film world. Most people considered her a snob, only intimates knew she was genuinely bored by such occasions”. Yet she appeared at Filmfare award functions in her trademark white saris and used to recite her own or Faiz’s ghazals on such occasions. She won the best actress award four times and there was one year when she was nominated in all three competing films as the best actor!

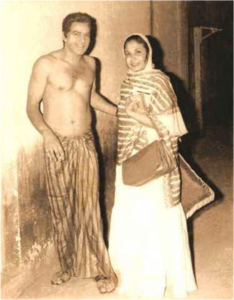

Meena’s love for cars is also a recurrent theme in the biography. She owned a Mercedes in those days and her first bout of success in early youth made her acquire a Plymouth. After her failed marriage with Amrohi, Meena’s drinking became excessive and so did the pursuit of pleasure. She had three key relationships afterwards (many other short term liaisons have been cited by the vernacular press but Mehta does not include them in the book). The two notable ones were with Dharmendra who was patronized by Meena and owed his stardom to her facilitation. She acted with him and as Mehta tells us, coached him in the art of cinema. By this time Meena must have acted in nearly 90 films. However, a much younger and already married Dharmendra had nothing to offer in terms of the love and security Meena was searching for.

“A much younger and married Dharmendra had nothing to offer in terms of the love and security Meena craved”

The other elusive relationship was with Gulzar who incidentally remained loyal and close to her and was even present in the hospital when her condition deteriorated. Mehta himself could not ascertain the nature of this relationship as Gulzar ji remained reticent during various interactions with Mehta. One indicator is quite telling: Meena left all her diaries with Gulzar and most of their contents remain unpublished to date. It is extremely important that Gulzar Saheb make them public. After all, Meena belongs to her fans and the larger cultural canvas of the subcontinent.

“She left all her diaries with Gulzar and most of their contents remain unpublished”

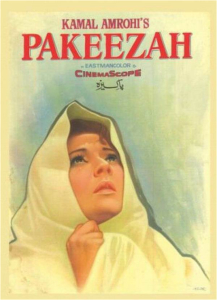

‘Our heorine’ passed away within days of the release of her epic Pakeezah which took 14 years to complete. Such was her devotion to the medium that Meena finished the film despite her ill-health and bitterness with Amrohi. The film did not get instant positive response and initial reviews were discouraging. But her death changed fortunes as Pakeezah became a platform for her fans to pay homage to their enchantress-heroine. Pakeezah was a story of a ‘pure’, love-seeking woman and cemented that lasting popular image of the heroine: deep sorrow, longing and unsaid verses in those beautiful eyes.

“To characterize her as a merely pitiful, lonely and tragic figure would be unfair”

Mehta appropriately grants himself some leeway by stating at the outset: “It would be a brave, possibly foolish man who would write a book on Meena Kumari without the necessary escape clause”. There are many more versions of Meena’s life but this one is a must read for it is simply written, gripping and brings forth a fulsome image of a complex woman. It is quite clear at the end of the book that Meena made her own choices and paid for them as well. But to characterize her as a merely pitiful, lonely and tragic figure would be unfair to someone so talented and intelligent. Her poetic skills merit a separate piece and I promise to do that once I locate all my dusted versions of her poetry picked up from old books stalls in Lahore’s Anarkali.

Mehta starts and concludes his book with a simple line that echoes what many of us tell ourselves: “Wish I had known you.”

– See more at: http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/the-real-meena-kumari/#sthash.KGCmGQtR.dpuf