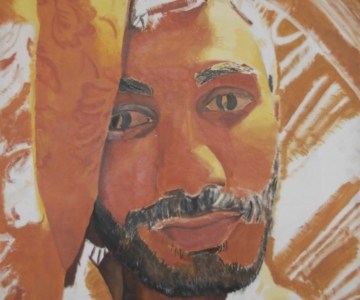

Steeped in the past, and yet, modernist in its application, neo miniature is the new face of Pakistani miniature painting and art. Having evolved as a genre that is entirely indigenous in its expressions, it has also globalized Pakistani cultural idiom and has inspired a generation of artists within and outside the country

Pakistani miniature painting and art. The survival of a revival

Raza Rumi believes the neo-miniature movement is located within the resilience of Pakistani society as well as its struggle to reinvent aesthetic and cultural parameters of identity.

My detailed report for DAWN:

Nearly two generations of Pakistani artists have experimented with the traditional genre of miniature painting and art; some have even gone on to expand its scope and vocabulary. It is on the shoulders of such artistic endeavor and innovation that Pakistan’s neo-miniature movement has now turned global.

Neo-miniatures retain traditional techniques while incorporating contemporary themes, and some have even deconstructed the format and articulated sensibilities that otherwise would be identified with post-modernism.

Its entry into Western markets galleries and private collections is are recognition of the rigorous technique and innovative thematic inferences employed by Pakistani artists. Undoubtedly, Pakistani art has found a discernible niche in the global art market.

In the post-modern framework, where skill has been put on the back burner in preference to conceptual art, miniature is viewed with much awe and fetches high prices, says Nafisa Rizvi, an eminent art critic and a curator. Gallery owners and curators tend to emphasize the painstaking and meticulous effort needed to undertake a painting of this nature.

The neo-miniature movement is not a continuation of tradition or a completely new event. It is located within the resilience of Pakistani society and its struggle to reinvent aesthetic and cultural parameters of identity and social change. This is one of the key reasons why the world takes it so seriously and provides patronage to it.

Rizvi notes that of the two Pakistani artists invited by documenta (an exhibition of contemporary art which takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany) for the first time in our history, one was the miniaturist Khadim Ali.

Khadim Ali, an Afghan Hazara, has found the freedom to express the persecution of Hazara community, something that may not have been possible without global patronage, explains Iftikhar Dadi, an art historian at Cornell University.

Pakistani artists who fetch the highest prices and are represented by galleries abroad include key miniaturists, adds Rizvi.

After 9/11, the miniature movement found renewed and greater resonance in the West. The earlier themes that the iconoclasts had chosen the burqa motif, clerics, nihilism had become both relevant and exploratory.

As Dadi puts it: The playfully subversive miniature was well-suited to participate in a globalised and post-modern cultural sphere in which Pakistani art is inextricably linked to diasporic practices, international mega-exhibitions and promotion by Western galleries.

The interest in Pakistan and the quest to understand it better also contributed to wider interest. Aisha Khalid’s work, for example, which questions the concept of veiling, gender hierarchies and the repetition of Arabesque pattern, found great traction.

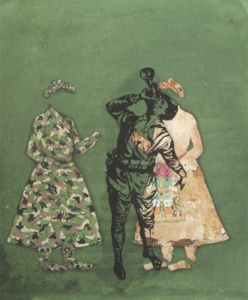

Saira Wasim’s explorations of the US foreign policy and the war on terror narratives under the Bush administration were visual allegories that highlighted manipulation and exercise of imperial power not unlike the Mughal court. Her works have also been used as book covers.

But the movement has had its naysayers too: art critic Virginia Whiles in her recent book Art and Polemic in Pakistan explains that the neo-miniature movement is split between the traditionalists, who prefer to work within conventional boundaries, and the iconoclasts, who have broken the shackles of convention and given the form a new dimension.

It is the power of the latter group that has turned the courtly miniature into a radical form of artistic expression. The movement therefore found resonance in the West, where Pakistani artists have negotiated global trends using the intimate, demanding techniques of miniature painting and art.

Many trailblazers in this group emerged from the National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore, originally known as the Mayo School of Art. The institution had been set up by the British in an attempt to preserve and mainstream traditional South Asian art forms.

With the decline of the Mughal Empire, the advent of British colonists and photography, tradition witnessed a rupture. Patronage, not unlike music, was relegated to regional kingdoms and principalities. Patronage had enabled the miniature painting and art forms to flourish for nearly a millennium; and the colonial period saw its decline.

But it was only in the 90s when younger artists such as Shahzia Sikander, Imran Qureshi, Aisha Khalid and others, under the tutelage of the legendary instructor Bashir Ahmed at the NCA spearheaded the new miniature movement. Almost all the influential contemporary miniature artists have been trained at this art institution.

Iftikhar Dadi credits Abdur Rahman Chughtai (1897-1975) as the first major Pakistani artist to revive Mughal miniature painting and art style after the independence. From 80s onwards, artist Zahoor ul Akhlaq (1941-1999) employed the stylistic features of the tradition to create a new, modern sensibility.

In fact, Akhlaq also oversaw the setting up of a miniature painting department at the NCA along with Bashir Ahmed. Akhlaq’s own work explored conceptual and formal scale of miniature painting. His vision became the basis for a major movement a decade later.

Critics such as late Akber Naqvi were initially skeptical about miniature’s revival. But ardent defenders such as artists-educators Salima Hashmi and Naazish Ataullah, among others, carried forward the legacy of Zahoor ul Akhlaq and some of their gifted students such as Shahzia Sikander and Imran Qureshi. Their involvement as academics is an important element of the revival and new avatar of the miniature movement.

But greater success abroad has also brought about greater critique and introspection at home: despite the wide corpus of outstanding artistic output and its global acceptance, there have been critical voices questioning the authenticity of tradition and practice.

Commodification, for instance, has been cited as a pitfall of this movement where, according to critics, some younger artists have indulged in copycat formulas for commercial success.

The rise of miniature painting and art at the end of the 20th century, according to Quddus Mirza, artist, art critic and educator, was a search for forging an identity in response to Western influences in realms of politics, culture, economy and science.

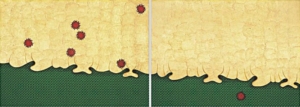

Miniature painting was viewed as an authentic aesthetic practice of the South Asian region. Mirza agrees that there was an element of exotica at work.

Foreign visitors preferred to purchase miniature paintings for its size, made with exquisite skill and labor, he says. With an increased attention of the outside world, local collectors also picked miniature as the most suitable art form. The local and global intertwined over time.

But the exoticism that miniature painting and art reproduce and reinforce, especially for the foreign market, is a matter of intense debate within Pakistani art circles.

Rizvi holds that allure of the miniature is embedded with shades of Oriental-ism as it stirs the exotica associated with traditions of the East.

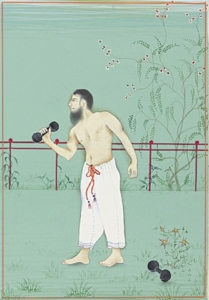

The flattened perspective, the bright jewel-like organic colors, the architectural details, and dress reiterate the South Asian cultures of yore, she contends.

But simultaneously, the art critic argues, many artists have climbed on to what has become a neo-miniature bandwagon as the market is not only accepting of this genre but displays all the signs of growing. While the market is currently undervalued, prices will continue to soar before they fall.

One reason for the sale of new miniature painting is that these are easy to display and transport, Rizvi adds.

Quddus Mirza confirms that miniature for both practical and aesthetic reasons is a sought after major at the NCA as the earlier artists successes have inspired a younger generation of students.

The relatively easy potential for selling, storing and making in comparison to other disciplines such as painting, printmaking and sculptures, which need larger studio space, storage, etc., makes it an attractive discipline, argues Mirza.

But artist Imran Qureshi dismisses the commodification argument and holds that miniature painting are just like other genres prints and paintings, etc.

In fact, he cautions, an inordinate focus on this aspect minimizes what the movement has already achieved in terms of globalizing Pakistani cultural idiom and inspiring a generation of artists within and outside Pakistan.

For those seeking inspiration, Shahzia Sikander remains the first of the radicals whose thesis work at the NCA subverted both the formalist pattern as well as the thematic content. Her famed work Scroll incorporated elements of architecture, autobiography and contemporary art sensibilities, thereby setting into motion a new vocabulary.

Sikander credits both the rigorous training by Bashir Ahmad and a lecture by Victoria and Albert Museum, (V&A) London, scholar Robert Skelton that gave her window on the diversity within the historical miniature painting genre itself.

Nafisa Rizvi holds that allure of the miniature is embedded with shades of Orientalism as it stirs the exotica associated with traditions of the East.

After completing her MFA from the United States, Sikander started exhibiting her works across the country and gradually built an audience that was ready to converse with the complexity and range of contemporary miniature painting and art form. Others followed suit.

In 1999, Sikander exhibited at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC. Initially there was limited interest in the miniature form and this was one of the reasons that I chose a contemporary art museum to highlight its relevance, she says.

Sikander wanted to reach out to critics and historians outside of the miniature painting field so that they could fathom the immense potential in the form.

Another celebrated miniaturist, Imran Qureshi holds that his training at the NCA made him discover a new language for the genre. The creative process emanating from his intimacy with the miniature form enabled him to break the boundaries as an independent artist.

In 2003, Qureshi curated the Karkhana project inspired by the Mughal court studio workshop and its first show. This collaborative endeavour included five other artists Aisha Khalid, Hasnat Mahmood, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Talha Rathore and Saira Wasim who worked on 12 paintings. This avant-garde, collective work was vital to re-imagination of miniature form in recent times. Karkhana democratised the art form, says Qureshi.

Other notable artists who have been torchbearers of this revivalist movement include Faiza Butt, Hamra Abbas, Ahsan Jamal, Mahreen Zuberi, Mohammad Zeeshan, Tazeen Qayyum, among others. As Qureshi explains, This is truly a popular and robust art movement in contemporary times.

Another artist trained in miniature craft who came to the US to study was Ambreen Butt. The West knew of miniature painting as the art of the other, almost folksy, says Butt. They had no idea of its contemporary practice up until the early 90s and academia had a major role in promoting it.

She adds that such amalgamation of the past and the present has fascinated global art viewers. I have been working for the past 22 years in the US but my connection with this genre keeps on redefining itself, she adds.

Imran Qureshi’s decade long exhibits in Sharjah, Europe and the US popularised the form and found a receptive art community of critics, collectors and galleries. His 2009 exhibit Hanging Fire at Asia Society Museum in New York and the installation commenting on terrorist violence among other themes, at the rooftop of Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013 testified to the adaptation of scale and drama within the genre of the miniature.

Meanwhile, Mirza believes that the practitioners of neo-miniature did not restrict themselves to the form, but created works in multiple mediums, formats, imagery and concerns.

Rashid Rana who is another globally renowned contemporary artist, was also trained at the NCA in similar traditions that Zahoor ul Akhlaq set during his teaching and art-practice. Rana works with the new media and even in his digital style, one of his 2002 works is entitled I love miniatures.

This poignant production weaves a Mughal Emperor’s profile through countless billboards for products and films. Rana’s work is both an extension and a critique of the tradition where structure of a miniature and its micro details can be explored and reinvented.

The immersion of neo-miniature in the academy and global art dynamic continues.

Sikander recalls that her decision, in the initial years, to work with the academic institutions across the US was instinctive. It has enabled the inclusion of contemporary miniature painting into textbooks and academic art schools.

Art 21 documentary in 1999-2000 focusing on my work at that time was reaching out to more than 5,000 high schools, says Sikander.

Qureshi was commissioned by London Underground and is currently working on a major show at Barbican London. In fact, his public installations in many countries have contributed to furthering the possibilities of this form.

Iftikhar Dadi articulates a similar view: Global patronage is not limited to art galleries or collectors. Private foundations, not-for-profit organisations and such other academic institutions have also espoused the extraordinary work coming out of Pakistan.

When did art not need legitimating by the state or market? argues Dadi. One can find individual artistic paths, but the terms of recognition are no longer national in today’s world.

Any art form to flourish requires a frame of recognition. The global patronage to the neo-miniature movement is constructing a new framework for Pakistani artists, both within and outside the country.

In fact, artistic experiments beyond the national boundaries have liberated artists, including the miniaturists, from the constraints of cultural and political environment in Pakistan. Without doubt, this is another testament to the possibilities inherent within the Indo-Persian miniature art form that finds in revival centred in Pakistan.