For nearly a fortnight, a motley group of clerics and their supporters have caused a blockade of Islamabad – the capital of a nuclear nation – protesting against an alleged offence to faith.

In October, a minor change in the oath taken by politicians had sparked protests. The change of words from ‘I solemnly swear’ to ‘I believe’ – that has now been reversed by the Parliament – in the ‘finality of the prophet Mohammad(PBUH)’ were deemed as sacrilegious by Tehreek Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), leading to calls for the resignation of the law minister and even the ouster of the government.

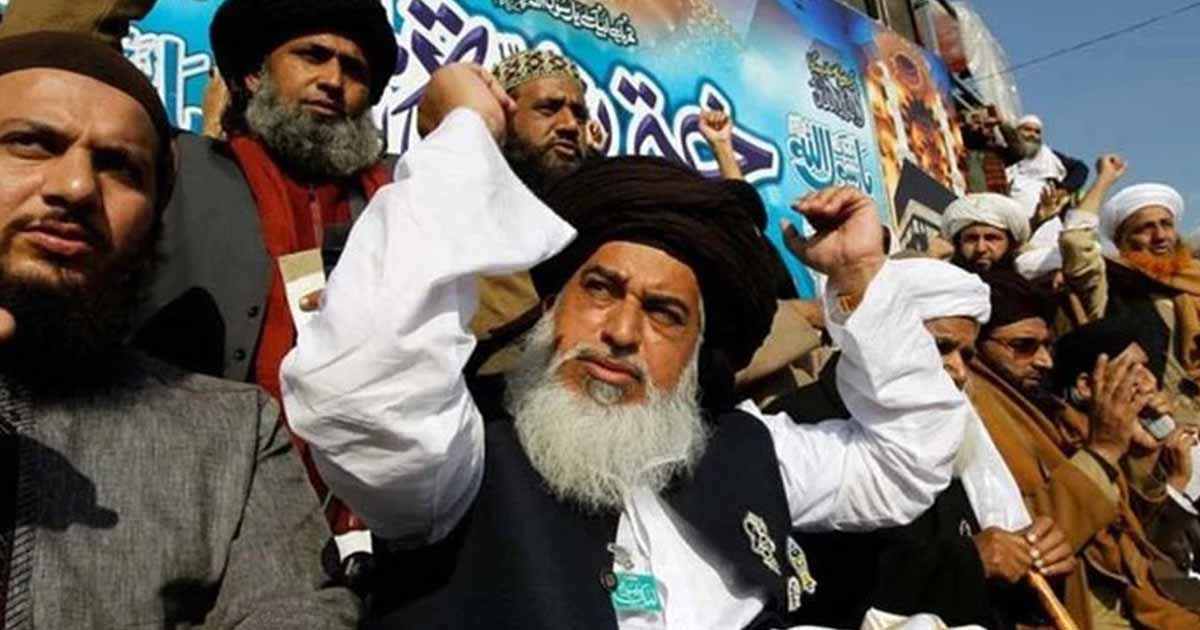

The TLP is a new addition to Pakistan’s countless Islamist groups. Unlike the well-known religious parties and jihadists, TLP adheres to the majority Sunni-barelvi sect. The party made its electoral debut in the recent Lahore by-election and earned a few thousand votes against the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) candidate who also happens to be the wife of the ousted Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. The TLP disturbingly calls Mumtaz Qadri a hero and claims to have launched a crusade against blasphemers in the country.

The government’s response to the ongoing sit-in and the resultant disturbance caused to the public has only exposed its ineptitude in handling the crisis.

Mobilisation of religious passions for political ends has been a familiar strategy since Pakistan’s inception. In fact, the demand for Pakistan to some degree also invoked the religious identity.

In analysing TLP’s politics, one need to also factor in a less popular view that groups such as TLP are part of the political engineering by country’s military establishment that wants to cut PML-N to size. Historically, the PML-N has enjoyed the support of large number of Barelvis in elections.

‘This situation [1953 Anti-Ahmadi riots] was brought about by people who wanted to get into power in the Centre. They thought that by creating unrest, the men at the helm of affairs in the Centre would have to go. The old tried method of attacking a religious minority sect called Ahmadis was used to inflame the minds of otherwise peaceful people.’ —Firoz Khan Noon

If there has been one constant in Pakistan’s troubled history; it is the convenient mixing of politics with religion. The early years of Pakistan set this trend and with time it has been impossible to reverse it. The Objectives Resolution passed by the Constituent Assembly in 1949 kick started the official announcement of the religious credence of the state. The Resolution remained a statement of intent but it found its way into the operative part of the constitution under General Ziaul Haq. Today, it is an open minefield – easy to ignite, exploit, and use as a threat.

It would be pertinent to recall the first instance after the creation of Pakistan where the issue of Khatm-e-Nabbuvat figured in street agitation. The 1953 anti-Ahmadi riots in Punjab led to the first ever imposition of Martial Law. The threat to Khatm-e-Nabbuvat (finality of Prophethood) is an appeal that few Muslims can choose to ignore. In 1953, a Bengali Prime Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin was at the helm and he had been trying to create a consensus around constitutional principles that would give East Pakistan (and smaller units) their fair share in governance. At the same time, Nazimuddin used religious clauses to build support. Nazimuddin, however, was pitted against the powerful West Pakistan establishment represented by Governor General Ghulam Mohammad, Iskander Mirza who was the defence secretary (and who engineered the 1958 coup) and Ayub Khan, the head of the Army.

Mumtaz Daultana, who ruled the Punjab province, was opposed to the constitutional principles put forward by Nazimuddin. Once again, religion was cleverly made a reason to cause disturbances. Daultana tacitly backed the Islamists – mainly the Ahrar and Jamaat-e-Islami – in demanding that central government should declare Ahmadis as non-Muslims and remove them from government positions. The protests turned violent when Nazimuddin ordered a crackdown in March 1953 and arrested key religious leaders including Maulana Maudoodi. To quell the agitation, the military was called in. According to historian K B Sayeed, it was Iskander Mirza who ordered Army action. Nazimuddin fired Daultana and replaced him with Malik Firoz Khan Noon. But his attempts to maintain power were short-lived. Within a month of the anti-Ahmadi riots and imposition of martial law, Nazimuddin was dismissed by Governor General Ghulam Mohammad.

Firoz Khan Noon, who later became the Prime Minister, has recorded some insights for posterity. In his memoir ‘From Memory’ (1966) he writes: ‘This situation [Anti-Ahmadi riots] was brought about by people who wanted to get into power in the Centre. They thought that by creating unrest, the men at the helm of affairs in the Centre would have to go. The old tried method of attacking a religious minority sect called Ahmadis was used to inflame the minds of otherwise peaceful people.’

In the same book, Noon identified the cabal of unelected officials – Ghulam Mohammad, Chahudri Mohammad Ali, and Iskander Mirza – as those at the helm of affairs. It is surprising to read about the ‘old tried method’ in 1950s for it sounds just like today.

In fact, this formula was employed time and again. The most dramatic invocation was the1977 movement against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto that called for Nizam-e-Mustafa (the system of the Prophet). Ironically, not unlike Nazimuddin, Bhutto was already appeasing the mullahs. The successive governments changed the blasphemy laws beyond repair by the 1990s.

The TLP’s outburst and antics are also a part of what has been happening in the recent tug of war. When Nawaz Sharif appointed the current Army Chief, Gen Bajwa, there were elements within the state that launched propaganda about Gen Bajwa’s alleged Ahmadi family connections. Meanwhile, the issue of blasphemy has been used to crush dissent on social media throughout 2017, discrediting dissenting speech by terming it as ‘blasphemous’. Then, after Nawaz’s ouster, death threats for blasphemy were aired most likely in response to his will to fight it out. But Nawaz’s son-in-law soon made a foul anti-Ahmadi speech and called for expulsion of Ahmadis from the Army (not too difficult to guess the target). And now, TLP is on the roads pressurising Nawaz’s successor in office.

It is mind boggling to count how many blasphemers there must be in the country if all the allegations were to be counted. What the elites don’t realise, however, is that this is no longer 1950s or 1970s. Whatever they do gets reported in the global media. They are bringing shame not just to Pakistan but also to the faith they are supposedly protecting in the land of the pure.

Published in Daily Times, November 19, 2017: Mixing politics with religion continues unabated