I grew up in Pakistan where we are taught about Sayyid Ahmad Khan throughout our school years as the grandfather of Muslim Nationalism in nineteenth century India. While it is true that Sayyid Ahmad was a Muslim reformer and activist, his appropriation by the Pakistani nation-state project has only obscured the expanse and range of his work and his deep engagement with both Muslims and non-Muslims in colonial India.

This essay1 will present a brief biography of Sayyid Ahmad Khan followed by the context in which he lived and how he made sense of the Muslim decline after the tumultuous events of 1857. The next section will focus on his services in education and raising awareness. His unconventional views on the need to reinterpret Islamic traditions will be discussed in the third section. Finally, this essay will highlight the emphasis on community, voluntary associations and the rich legacy that he left Muslims of Indian subcontinent and beyond.

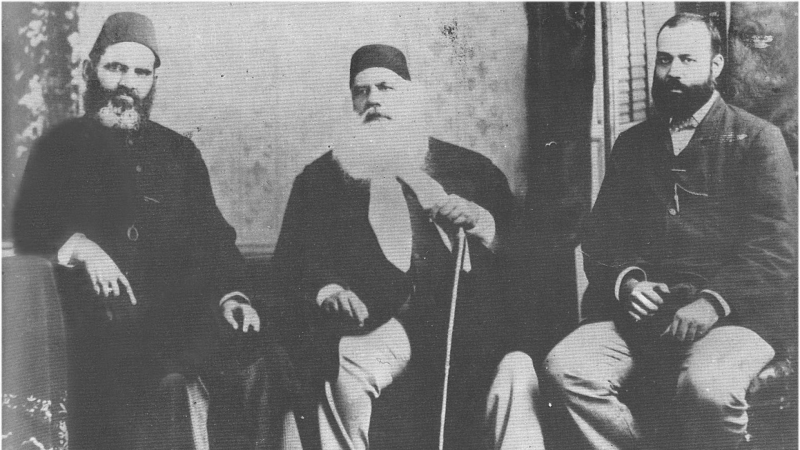

Sayyid Ahmad Khan, the nineteenth century reformer, writer and thinker has influenced generations for his emphasis on modern education.2 However, “the real significance of the man,” in the words of poet-philosopher Allama Iqbal “consists in the fact that he was the first Indian Muslim who felt the need of a fresh orientation of Islam and worked for it.” Born in Delhi on October 17, 1817, Sayyid Ahmad belonged to a household with strong ties to the fading Mughal nobility. His maternal grandfather, Khwajah Farid, was a wazir (vizier) in the court of Akbar Shah II; his paternal grandfather, Syed Hadi, held a mansab and the title of Jawwad Ali Khan in the court of King Alamgir II; and his father, Mir Muttaqi, was close to Akbar Shah since the days of his princehood.3

As a boy, Sayyid Ahmad studied Persian, Arabic, mathematics and medicine along with the Quran. In 1837, he joined the service of the English East India Company, starting as a munshi (clerk) and then rising to the rank of subordinate judge, beyond which Indian natives were not promoted before 1860.4 In 1867, he was posted as the judge of the Small Causes Court. Later he was nominated to the Viceroy’s Legislative Council in 1878.5

Throughout his government career, Sayyid Ahmad was also a dedicated educator, and he established Gulshan School at Muradabad in 1859 and Victoria School at Ghazipur in 1863. He took a trip to England in 1869-1870 and was greatly impressed by the English education system. He determined to set up a “Muslim Cambridge” in India on his return. In 1875, he laid the foundation of a school in Aligarh modeled after British boarding schools, which became the Mohammad Anglo-Oriental College (MAO College) in 1877 and then the famous Aligarh Muslim University in 1920, proudly carrying forward his legacy down to this day.

Before the establishment of the MAO college, in 1864, Sayyid Ahmad started the Scientific Society, with the purpose of translating important western texts into Urdu. From the Scientific Society, he launched the multilingual Aligarh Institute Gazette in 1866 and Tehzeb-ul-Akhlaq (The Mohammadan Social Reformer) in 1870, with the purposes of bringing elements of Islam and modern Europe closer together. Sayyid Ahmad was also a prolific author, and some of his most notable books include Athar-al-Sanadeed (Great Monuments, 1847); Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian Revolt, 1859); Tabyin-ul-Kalam (The Mohammadan Commentary on the Holy Bible, 1862); and The Loyal Mohammadens of India (1860).

Turbulent Context

It is important to understand the context in which Khan lived and worked. During 1757-1857, Mughal Muslim power dwindled as the British expanded their influence and continued to annex territories in the Indian subcontinent. Following the 1857 War of Independence (also known as “Mutiny”, “revolt” and “ghaddar”), the Muslims were recognized as a major threat by the colonial power and, in the decades to come, the Muslims lost much of their influence after centuries of enjoying power in medieval India.

The decade of the 1850s had a profound impact on Sayyid Ahmad. Some of his relatives died in the Mutiny, while his own house was attacked and looted. But much more than his personal loss, he was concerned about the treatment received by Muslims following the War of Independence. In his words, “Post-ghaddar, I was not disappointed by looting of my house and loss of belongings. I was disturbed due to the ruination of my qaum [community or nation].”6

This destruction of Sayyid Ahmad’s qaum was a result of mutual suspicion between the Muslims and British. The British sought to hold Muslims responsible as the main instigators of the Mutiny, and Muslims were subject to discrimination and harsh treatment. Muslims also spurned the British way of life, thus isolating themselves further inside their religious community. India’s Muslims, unlike their Hindu counterparts, rejected and shied away from Western education. As the historian K. K. Aziz notes:

The Muslims did not take to the English language, and thus denied themselves opportunities of material as well as intellectual progress. Material, because Government jobs were open only to English-knowing persons; intellectual, because the entire corpus of Western knowledge and learning was shut out from them.7

Sayyid Ahmad could well see the harm that Muslims caused themselves through their rejection of Western education. He, therefore, urged them passionately to learn English, rightly observing that by failing to learn the rulers’ language, the Indian Muslims “self-excluded” themselves from the mainstream society in the subcontinent. In his words, “If Muslims do not take to the system of education introduced by the British, they will not only remain a backward community but will sink lower and lower until there will be no hope of recovery left to them.”8 He understood the fear faced by Muslims of being pulled away from their religion if they were to adopt the language of the “infidels,” but Sayyid Ahmad reasoned: “No religious prejudices interfere with our learning any language spoken by any of the many nations of the world. From remote antiquity have we studied Persian, and no prejudice has ever interfered with the study of that language.” 9 Why then, he asked, should Muslims be prejudiced against learning the English language?

Sir Sayyid linked the Indian Muslim’s unwillingness to adopt the foreign education system with a kind of mental enslavement to formal religious tradition. It is true, by that time, Muslim societies around the world had already long felt the need for a renewal (tajdid) in the Muslim way of life, as the industrial and scientific revolutions had completely changed the ways communities everywhere organized themselves. Interestingly, the early reformist attempts of the time would both define themselves in opposition to Western cultural and political hegemony, while also making use of Western knowledge and technology, as the need required. 10 Like the other modernists of his era—among them, Sayyid Amir ‘Ali (1849-1928), Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897), Namik Kemel (1840-1888) and Shaykh Muhammad ‘Abduh (1850-1905) — Sayyid Ahmad was deeply concerned with the state of Muslims in a world dominated by European colonizing powers. However, he was among the first to realize the urgency of embracing rather than opposing the influences of the changing milieu, as his thought would also have the most profound and lasting effect on the Indian Muslims’ way of life. His embracement of secular learning together with the English language was arguably the most powerful and radical model for Muslim education in nineteenth century India.

Embracing Modernity and Reform

The diverse Muslim reformist currents of Sayyid Ahmad’s time have succinctly been summarized by Francis Robinson. These included: (a) ending the total authority of the past as Muslims sought new ways of making revelation and tradition relevant to the present; (b) bringing “human will” to the center, as Muslims realized that in a world without political power it is only through their will that an Islamic society could be created on earth; (c) stressing the need for the transformation of the self, which can be accomplished through willed activity, in order to achieve self-reflectiveness, self-affirmation and individuality of the self; (d) moving from scripturalism to a rational conception of Islam as an ideology; and, finally, (e) entering into a process of secularization.11

The emphasis on personal responsibility before God was widely seen as a necessary component of Muslim reform efforts—and it was equally a central issue for Sayyid Ahmad. However, Sayyid Ahmad’s thinking went far beyond all his contemporaries, and practically placed all of the received wisdom from tradition up for a rigorous test against reason. The stance he took—a call for the reexamination of every aspect of faith—was radical not just by the standards of his time but even for today. He himself had little doubts about his position, and was emphatic in embracing reason, even if it meant doing away with some of the most sacred traditions of Islam. To him, faith ought to aspire to certainty akin to that of empirical knowledge:

I concluded that faith (iman) cannot be without certainty (yaqin) and certainty cannot be without knowledge (ilm [This certainty should be] like the certainty about ten being more than three, so that its truth is enduring… Then I asked myself how reason can with certainty remain free from error. I admitted that such certainty is not really obtainable. Only if reason is used constantly can the error of the reason of one person be corrected by the reason of a second person and the reasonings of one period by the reasonings of a second.12

He was concerned about the past’s total authority on Muslims’ minds—even when they lived in an altogether novel milieu in which vast Muslim empires were falling apart. The Europeans and their Enlightenment tradition were decisively ascendent. Sayyid Ahmad thus saw the need for new way of thinking in the Muslim community, one that had to incorporate enlightenment, modernity and the tools of scientific inquiry. Islam is not against modernity, he argued. In a speech in Lahore in 1884, he asserted, “Today we are, as before, in need of modern ilm-al-kalam [theology], by which we should either refute the doctrines of the modern sciences or undermine their foundations, or show that they are in conformity with the articles of Islamic faith.”13

Sayyid Ahmed was particular about the source of religious dictums. He rejected the institution of ijma, that is, the power of defining a religious principle through consensus among Muslim theologians. 14 He averred that the Quran was addressed to each person, that every person had to ponder it for himself, and also that the right to understand the holy book’s meaning could not be taken away from any individual. Furthermore, he professed the practice of ijtihad, or independent reasoning, to be every Muslim’s right, that is, every Muslim had a right and a duty to use reason and strive for the true meaning of Quran. In this, he argued Muslims should always be attentive to the historical changes in the world around them, and that they should then put their religious positions and insights up for discussion, and strive collectively to arrive at a new consensus. Thus, he held the use of reason and discussion with others to be of paramount importance, while rejecting the unquestioned authority enjoyed by theologians and tradition.

In this vein, Sayyid Ahmad himself published an exegesis of the Quran, Tafsir-ul-Quran, in a series between 1880 and 1904. In it, he sought to show the compatibility between Quran and the modern sciences. He also tried to resolve long-standing difficulties posed by traditional sources using modern knowledge. In his Tafsir, Sayyid Ahmad sought to provide a rational interpretation of the ‘truths’ in the Quran and, accordingly, he addressed his book particularly to those Muslims who were looking for such an interpretation.15

Sayyid Ahmad spelled out a list of principles for this project which he prefaced in his Tafsir. One of these principles stated that the “word of God” could not be in contradiction with the “work of God.” In other words, the meaning of the Quran could never be in contradiction with the Laws of Nature. This insight led Sayyid Ahmad to embrace some controversial positions, including his rejection of angels, devils and even miracles—including those of the prophets. 16 He once asserted: “I desire not a Quran as a message from the Trusty Gabriel. The Quran that I possess is altogether the discourse of the Beloved.”17 Such radical departures from orthodoxy are testimony that once his principles were laid out, Sayyid Ahmad was consistent and unyielding in their observance. He had a clear vision and a goal, aptly captured in his words: “Science shall be in our right hand and philosophy in our left; and on our head shall be the crown of ‘There is no God but Allah and Mohammad is his Apostle.’”18

Some of his other radical departures from orthodoxy entailed rejecting a large number of hadiths and his claim that hadiths could only be of limited assistance in interpreting the Quran;19 his rejection of Prophet Muhammad’s night journey (al-isra) as nothing more than a dream, “neither a physical nor a spiritual experience”;20 his rejection of several penal injunctions, like cutting of the hand and stoning;21 his opposition to polygamy, as something the modern world did not need anymore, like slavery, which had been impracticable to abolish completely at the time of the Prophet;22 and his justification for charging interest on money lent to the well-to-do.23

Moreover, he also opposed the equation of jihad with wars that were fought to achieve political ends. Significantly, he excluded the majority of wars fought between Muslims and non-Muslims over the course of history, including the 1857 Mutiny, from wars fought for self-defense or religious freedom, which were the only two kinds of war that could justly be considered jihad.24 He warned against identifying one’s political purposes with the Will of God:

It should be borne in mind that the wars of the present day … cannot be taken as wars of religions or crusades, because they are not undertaken with religious motives; but they are entirely based upon political matters and have nothing to do with Islamic or religious wars.25

In short, Sayyid Ahmad called for a sweeping reappraisal of orthodox principles in every aspect of Muslim faith and law. Seeing as the words of the Quran as central to Islamic faith, he argued that it need not have a singular interpretation; instead, there should be commentaries on all the Quran’s different interpretations, and the readers must be allowed to choose the interpretation that seems the most valid to them. Moreover, the choice a reader makes about his preferred commentary must not be the basis of his inclusion or exclusion in the Muslim community, he argued.26 In fact, to Sayyid Ahmad, in Sheila McDonough’s words, “the unchanging element in human religiousness was the aspect of personal relation with God.”27

Thus, he would, under no circumstances, circumvent the study of nature, which he identified as the “higher principle” needed to interpret scripture.28 Nature represented the “work of God” which, as noted above, could not stand in contradiction to the “word of God,” and which needed to be discovered and understood by science. The resulting tension of this unorthodox position was that, in Shamim Akhtar’s words, Sayyid Ahmed found himself “standing on a ground, where what appeared to others as a linguistically natural meaning of a Quranic verse, became unnatural to him because it would then contradict our science-derived knowledge of nature.”29But Sayyid Ahmad was undeterred by this tension (and the concomitant criticism). He was secure in his conviction that “there is perhaps no religion upon earth superior to [Islam] in respect of the liberty of judgement which it grants in matters of religious faith,” thus rendering the fear of upending previous notions of faith to be unnecessary.30 He refused to allow logic to be undermined by any dictum of faith. Following in the footsteps of the great Islamic scholars al-Ghazali and al-Razi, Sayyid Ahmad considered the ability to make logical deductions a necessary prerequisite to doing ijtihad and, in fact, found it even more necessary than Islamic scholarship. 31

The result of such radical ideas was, understandably, sharp opposition and criticism from all sides. His identification of Nature as the higher principle against which scriptural interpretation should be tested earned him the derisive nickname of “neichari”—the “naturalist.” Many theologians issued fatwas against him for being a heretic, apostate or atheist. One of his contemporaries even went to Makkah in order that a fatwa be pronounced against him from the holiest site in Islam. 32 His famous contemporary Jamal al-Din Afghani wrote an essay, “Dahriyun fi`l Hind” (“The Materialists of India”), in which he strongly condemned Sayyid Ahmad in the words: “He appeared in the guise of naturalists [materialists], and proclaimed that nothing exists but blind nature … and that all the prophets were naturalists … He called himself a neicheri or naturalist, and began to seduce the sons of the rich, who were frivolous young men.” 33

It wasn’t only his contemporary theologians whose severe opposition he had to suffer. Sayyid Ahmad also faced bitterness from his friends and family. Mushirul Hassan notes that one of Sayyid Ahmad’s aunts refused to see him “on account of his taking too kindly to the culture of the foreigner and the infidel.”34 Even in Aligarh, as Shamim Akhtar highlights, his friend and hitherto strong supporter Nawab Mohsinul Mulk denounced Sayyid Ahmad’s radical ideas about the constant need of reinterpreting the Quran. Mohsinul Mulk subsequently let these ideas be quietly buried, as he took over the management of the college.35

Unsurprisingly, many of Sayyid Ahmad’s ideas remain the target of vehement criticism by orthodox theologians down to this day. Religious scholars in South Asia continually attempt to pick up inconsistencies in his philosophy, whereas some anti-colonialists frown at his enthusiastic endorsement of and closeness to the West.

Seeing India Whole

The reverence which Sayyid Ahmad commands among not only Muslims but also non-Muslims of the subcontinent, and especially (though in some ways ironically) in Pakistan, far outweigh any critique against him. It also testifies to his farsightedness and his relevance in our context. Moreover, it would be as unfair to label Sayyid Ahmad as merely an Islamic reformist as appropriating him to the Pakistan movement or the two-nation theory. On the contrary, it is the very qualities of inclusivity, tolerance, and inter-cultural cooperation which most accurately define the multifaceted person of Sayyad Ahmad Khan.

As it becomes abundantly clear from his reformist project, Sayyid Ahmad did not see cultures as fixed identities. His great efforts to convince his coreligionists to move away from tradition and to adopt modern practices and outlooks bear witness to this fact. Yet, his efforts were far from being limited either to merely Indian Muslims as the beneficiaries, or to the adoption of exclusively British ways as the end-goal. Yasmin Saikia and M Raisur Rahman in the Cambridge Companion to Sayyid Ahmad Khan write:

the ‘modern’ project that Sayyid Ahmad inaugurated for Muslims was not an effort to become British-like… He advocated it as a capacity to change. Thus, he remained committed to Indian heritage and history while simultaneously calling for change to adapt to the current times.36

Sayyid Ahmad’s efforts are conventionally seen as predominantly driven to help the Muslims of India as they were the ones who were most in need of a reorientation and reconciliation with modernity. But by no means did this mean that Sayyid Ahmad only thought of the Muslims, to the exclusion of all the other communities living in India. On the contrary, Sayyid Ahmad believed in the Hindustani identity, in which he included not only both Muslims and Hindus, but even the British as “representatives of another culture with much potential to contribute to India’s advancement.” 37In his words:

By the word qaum, I mean both Hindus and Muslims. In my opinion it matters not whatever be their religious belief because we cannot see anything of it. But what we see is that all of us, whether Hindus or Muslims, live on one soil, are governed by one and the same ruler, have the same sources of benefits and equally share the hardships of famine.38

In its first few years, the MAO College had more Hindu students than Muslims, and its first graduate, Ishwari Prasad, was a Hindu.39 Sayyad Ahmad forbade cow-slaughter in the college and, in public, counseled against it as he tried to encourage a relationship of respect and friendship between Muslims and Hindus. Even on more private occasions, he never let up his efforts toward this end. His words to his guests on the occasion of his grandson’s rasm-e-bismillah, for example, are recorded thus: “My cleanshaven friend (Das) is here and my grandson is sitting beside him. He is my friend and brother. Syed Mahmood [Sir Syed’s son] calls him uncle while he is ‘dada Raja’ to my grandson Ross Masood.”40

On the matter of religion, Sayyid Ahmad believed in God’s transcendence beyond religion or methods of worship. In one of his letters, after describing a Christian Sunday service on board a ship to England, he reflects:

I saw the way God was prayed to… Some men bow down to idols; others address Him seated on chairs, with heads uncovered; some worship Him with head covered and beads on, with hands clasped in profound respect; many abuse Him, but He cares naught for this. He is indeed the only one who is possessed of the attribute of catholicity.41

All the same, he himself identified securely as a Musalman-e-Hind—a Muslim of India. There was no paradox in his mind in asserting both these identities (Muslim and Indian), even as the modern nation-states of Pakistan and India tend to see such an assertiveness as suspicious. It may parenthetically be noted that the nature of this suspiciousness is, again, exclusivity—which was exactly what Sayyid Ahmad, even at that time, sought to fight against.

Sheila McDonough has focused on Sayyid Ahmad’s career as an ethicist. Even as his efforts had both a political and a religious bent to them, his emphasis was on the inculcation of cooperative action in the community, through the ideals of justice, mercy and the formation of moral and empathetic consciences in individuals—which, to him, was the essence of religion. 42 These, in his view, are also the hallmark virtues proclaimed by the Quran, which, if adopted, would sufficiently provide one with the faculty to reason in accordance with nature as well as social morality. Conversely, the absence of akhlaq (code of ethics) would lead to bigotry and the cessation of progress. As Sheila McDonough writes, tolerance did not mean “passive acceptance” of others to him. 43 Instead, a community’s members were obliged to strive for social harmony by discussing matters of shared import and arriving at common points through persuasion and mutual respect. For this purpose, he did not consider the state to be the main agent of reform aimed at social harmony; instead, every member of the community was responsible and needed to inculcate the virtue of “self-help” in his or herself. 44

Conclusion

Sayyid Ahmad’s legacy was carried forward by the Aligarh Movement, which resonated throughout the Indian subcontinent for decades. AMU alumni’s central importance in the Indian independence movement is undeniable. Sayyid Ahmad was pivotal in generating the consciousness among Indians about their rights. Modern and educated Muslims emerged from AMU and asserted their demand for political rights and shared government in India. Both the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League carried the legacy of AMU in their ranks.

Even more, the AMU alumni spread throughout the world, carrying the message of empowerment through education with them. These achievements are none too surprising considering Sayyid Ahmad himself envisioned it as the objective of his untiring efforts, which, in his words, was “To go throughout the length and breadth of the land to preach the message of free inquiry, large-hearted toleration and pure morality that is possible only with modern education.”45

The effects of his efforts can be felt even today. AMU remarkably blended the British, Indian and Muslim cultures to invent something original for Muslim community in the Indian subcontinent. That legacy lives on.

Sayyid Ahmad’s public life was marked by thinking and acting far ahead of his times. Even in his quest to reform Muslims, he displayed no bias toward non-Muslims and perhaps this is why his profound work defies the nation-states of India and Pakistan. It is time to liberate Sayyid Ahmad from the national projects of Pakistan and India and instead focus on the example he set by promoting education, building institutions, and looking ahead instead of the imagined pasts.

To use the Aristotelian idea of seeing the light in the darkest moments, Sayyid Ahmad remains a beacon that provides a guide to Muslim cultures across the globe to employ the ideas from religion and cultural traditions as instruments of transformation instead of being trapped by them.

Sayyid Ahmad’s emphasis on education, reform and blending tradition with modernity remains as important today as it was two centuries ago. The heterogenous Muslim world or Ummah, as it is popularly known, could benefit from refocusing its energies on modern education, opening up their societies to pluralist debates, and revisiting and re-adjusting jurisprudence in line with the local and global imperatives of the twenty first century.

________________________________________________________________________________