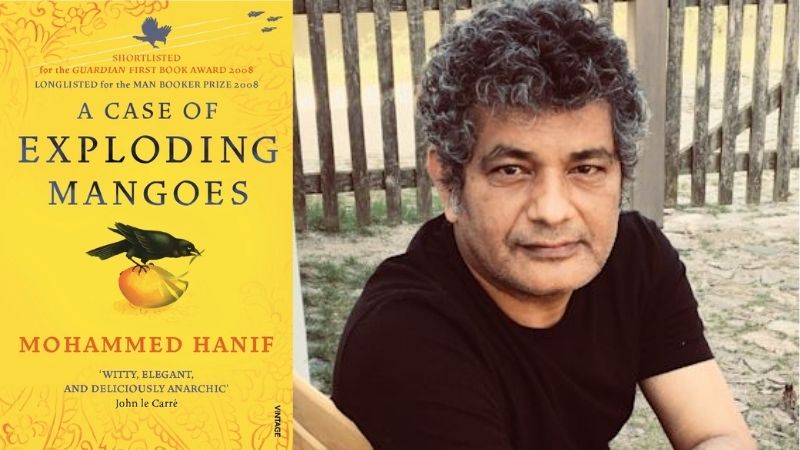

Found a great excerpt from Mohammed Hanif’s novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes where he recounts on his time at the Pakistani military academy during General Zia’s regime.

Once upon a time, when I was eighteen, I found myself locked up in Pakistan Air Force Academy’s cell along with my friend and partner-in-crime, Khalid Saifullah. We had thought we were doing charity work but the Academy officers obviously didn’t share our ideals. We had been caught trying to help out another class mate pass his chemistry exam, something he had failed to do twice already and this was his last chance to save himself from being expelled. The logistics of our rescue effort involved a wireless set improvised in the Sunday Hobbies Club, a microphone concealed in a crap bandage around the left elbow of our academically challenged friend, and a Sanyo FM radio receiver. We were running our operation from the roof top of a building next to the examination hall. We were caught red-handed whispering reversible chemical equation into the transistor.

Once upon a time, when I was eighteen, I found myself locked up in Pakistan Air Force Academy’s cell along with my friend and partner-in-crime, Khalid Saifullah. We had thought we were doing charity work but the Academy officers obviously didn’t share our ideals. We had been caught trying to help out another class mate pass his chemistry exam, something he had failed to do twice already and this was his last chance to save himself from being expelled. The logistics of our rescue effort involved a wireless set improvised in the Sunday Hobbies Club, a microphone concealed in a crap bandage around the left elbow of our academically challenged friend, and a Sanyo FM radio receiver. We were running our operation from the roof top of a building next to the examination hall. We were caught red-handed whispering reversible chemical equation into the transistor.

We were in breach of every single standard operating procedure in the Academy rule book, and faced certain expulsion. We had just started our glorious careers and now we faced the prospects of being sent home and having to explain to our parents that how, instead of training to become gentlemen-officers, we were running an exam-cheating-mafia from the rooftop of the most well-disciplined training institute in the country.

For two days, while we waited in that cell to find out about our fate, we planned our future. Khalid, always the world-wise in this outfit, immediately decided that he was going to join the merchant navy and travel the world. I tried hard to think what I would do. I came from a farming family where even the most adventurous members of our clan had only managed to branch out into planting sugarcane instead of potatoes. Education, jobs, careers were absolutely alien concepts. The Academy was supposed to be my escape from a lifetime that revolved around wildly fluctuating potato crop cycles. And here I was, already a prisoner of sorts, facing a journey back to a life I thought I had left behind.

“Maybe I’ll become a teacher,” I said vaguely. The farmers in my village used to show some vague respect to teachers in the primary school I attended. “Or a mechanic.” I was a member of the car-maintenance club in the hobbies club after all. It was considered an elite club since there was no car to maintain. It was basically a hobbies club for people who hated hobbies.

“You can’t even change a bloody tyre,”Khalid reminded me.

We managed to stave off the impending expulsion through a combination of confession and denial: we lied (we were listening to cricket commentary on the transistor radio), we grovelled (we were ashamed, ashamed, ashamed of our un-officer like behaviour) and we pleaded our undying passion for defending the borders of our motherland. They looked at our relatively clean record, our sterling academic achievements and let us off the hook and awarded us a punishment considered just short of expulsion. We were barred from entering the Academy’s TV room–and walking. For forty-one days. During the punishment period, we had to stay in uniform from dawn till dusk and when ever we were required to go from point a to b we had to run. Khalid went on to become a fairly good marathon runner (before, years later, dying in an air crash, while trying to pull a spectacular but impossible manoeuvre in Mirage fighter plane). I discovered Academy’s library.

I had barely noticed that the college had a very well stocked library. We knew it was there, we occasionally used it as a quite corner to hatch conspiracies but I had never noticed that the long rambling hall was lined with cupboards full of books. All the cupboards were locked but you could see pristine untouchable books behind their glass doors. The librarian, an eagle-nosed old civilian, walked around with a large bunch of jangling keys although his wares were not in any danger of being stolen. I was to find out later that he was quite a professional. The library was immaculately catalogued. You could of course go to him, fill out a form and request a book. But I never actually saw anybody fill out a form. I spent some afternoons staring at the books from behind the glass doors as my classmates watched videos in the TV room (including the fellow who had scraped through his chemistry exam and survived but would die years later in our current president’s General Pervez Musharraf’s moronic military adventure in Kargil on India-Pakistan border).

How do you ask for a book when you are eighteen, and have been brought up in a household where the only book was the Quran and the only reading material an occasional old newspaper left behind by a visitor from the city. “I want that book,” I asked the librarian pointing tentatively towards a cupboard which contained a thick volume of something call The Great Escapes. The librarian, relieved at having found a customer, took out his bunch of keys, removed a key and asked me to go get it myself. I took my time and browsed for a long time before filling out the form and borrowing the book. So grateful was I for getting that book that I brought him a samosa and cup of tea next day. That turned out to be a very good investment as the librarian handed me the bunch of his keys as soon as I entered. I browsed randomly, recklessly, read first paragraphs, author’s bios and made naïve judgments. The Cross of Iron wasn’t a religious thriller but a war novel. Crime and Punishment had very little crime in it. Was Rushdie related to the famous pop singer Ahmed Rushdie? Mario Puzo and Mario Vargas Llosa. The strange covers of Borges. Abdullah Hussain, I had heard of. A whole shelf devoted to Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Chronicle. Was that little book about the wrecked ship really a true story? I didn’t know which one was a thriller and which one was literary. As I lay Dying, sounds like a nice title so let’s read it. So does Valley of the Dolls. It is probably not the right way to read.

Discovering books was like a discovering second adolescence. I discovered new sensations in my body. It was even better. It was guilt free and I could show off.

Not that anyone except my librarian friend was impressed.

Outside the library, the world revolved around parade square, hockey fields and series of punishments and rewards that didn’t seem very different from each other. The vocabulary used to run the Academy life comprised of about fifty words, half of which were variations on the word ‘balls.’. Every order began or ended with balls, it was used as verb, adjective, qualifier or just simply a howl. Balls to you. Balls to mother, my balls, I’ll cut your balls…. Every order, every threat, every compliment was a variation on the same testicular theme. Now that I look back at, it is quite obvious that this place was drowning in its own testosterone.

From outside life could seem orderly. Uniforms were starched, rifles were oiled and sessions on the parade square hard and long. I yearned for that jangling of the keys in the library corridors. Once I was caught in my Navigation class reading Notes From Underground hidden under a map that I was supposed to be studying.

After our second year in the Academy, there were sudden attempts to turn us into good Muslims. Compulsory prayers. Quran lectures. Islamic Studies classes. In the third year we were caught stealing oranges from a neighbourhood orchard and as a punishment we were sent out to a mosque outside the Academy where Muslim cousins of Jehovah’s Witnesses taught us how to knock on random doors and preach Islam.

“But they are all Muslims,” I had protested.

“So are you,” came the reply. “And look at yourself.”

At that time I didn’t realise that we were an experiment in Islamisation of the whole society. General Zia was a distant presence. He was our commander-in-chief and the permanent president of Pakistan. He thought he was never going to die. So did we.

Years later sitting in the officers’ mess of a Karachi air base, we heard about the plane crash that killed him and several other generals. We were sad about the pilots and the crew of the plane. To drown our sorrows we pooled our meagre savings, ordered a bottle of Black Label whiskey, and instead of hiding in our bachelor quarters as we normally did, we opened the bottle in the officers’ mess TV room and discussed our future. I left the air force a month later.

Hanif is the head of BBC Urdu in London.

Source: Tehelka Magazine, Vol 5, Issue 22, Dated june 07, 2008