An amended, rationalised HEC needs to stay in place

The 18th Amendment approved by the Parliament in 2010 signified a new era in Pakistan’s troubled federalism. Given our turbulent constitutional history, the new governance arrangements approved by all parties and federating units settled for a leaner centre and addressed long-standing demands of provincial autonomy. But the implementation of this amendment has been slower than expected, largely for reasons of capacity both at the federal and provincial levels. Despite the constraints, the Implementation Commission has delivered fairly well. Thus far, ten ministries have been devolved. Five ministries — local government, special initiatives, zakat & ushr, population welfare and youth affairs — were devolved in late December 2010. The recent batch of the federal ministries includes: ministries of education, social welfare and special education, Tourism, livestock and dairy and culture.

Media rants:

In recent days, a new controversy on the devolution of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) has plagued the implementation process with respect to the 18th Amendment. Television channels have aired the views of technical experts as well as the usual suspects who rant on every talk show on almost every subject under the sun, be it defence, culture, or cricket. The move towards the devolution of the HEC’s powers and functions to provinces has been construed as another move by the semi-literate and ‘corrupt’ politicians to thwart the degree validation process, which has been part of our pseudo political discourse. Such an argument is pretty lame, as the rule to have a degree to be eligible for an election has been done away with. The Musharraf scheme of a grand HEC, BA-holding legislators and ‘controlled democracy’ obviously failed in 2008 when the electorate rejected his party and sent representatives who sent him home.

A non-discourse:

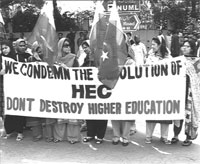

Most of what has been said on the HEC constitutes a plethora of comments, hysterics and ‘opinions’ on the subject, which has sidetracked the debate altogether. From a national discourse on fostering federalism, we are now arguing whether HEC was an effective body or not? There have been sporadic protests — overplayed by the media — and random statements of Vice Chancellors who seem to be vacillating from one position to another. Furthermore, former head of the HEC, the talented Dr Atta-ur-Rahman, has not helped matters either. His direct invitation to the Army to step in and rescue the HEC is simply problematic. What do the armed forces have to do with this issue: they are legally not in charge; and by an educationist to make such wild calls, we can easily surmise that Pakistan’s democracy remains a sham, especially when it comes to the educated elite.

Sanity, at last:

Najam Sethi on his TV show argued for a reasoned debate on the HEC issue and emphasised that devolution of powers or functions to the provinces cannot be compromised. In a follow-up tweet on the Internet, he added: “HEC debate should be how to minimally retain its best federal and international aspects while gradually transiting to maximally efficient devolution.” Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy, otherwise a fierce critic of the HEC, has also alerted that a sudden dissolution of HEC will result in a ‘free fall’, due to a lack of technical capacities in the provinces and the important work that the HEC was undertaking. Similarly, Dr Pervez Tahir, former Chief Economist of the country, has also argued the HEC case in his op-eds published in an English daily. (8 April, 2011). Skeptics have also argued that we may lose nearly half a billion dollars of foreign aid due to be directed towards higher education reform in the country. Feisel Naqvi has made an important point that specialized regulation of higher education requires advanced capacities that are missing in the provinces.

Devolution, a must:

Conversely, the passionate proponents of total devolution of HEC — unsurprisingly from the smaller provinces — argue that this body had not created a revolution despite the sevenfold increase in its budget during the Musharraf era. Instances have been cited where the HEC failed to regulate many institutions, especially those related to the armed forces and had let many malpractices continue in the country. One firebrand MNA from Awami National Party opined during a-discussion, “I am convinced standards of education in general and higher education in particular will improve when HEC is devolved to the provinces. I think we should all welcome the change and extend support to the provincial governments to ensure the devolution process is effective and smooth.” Dr Ayesha Siddiqa, the bold critic of Pakistan’s security establishment has also questioned the efficacy of HEC discussions and supported its full devotion.

Unpacking the issues:

Centralisation of HEC planning and resource management is the issue here, not the regulatory aspects per se. What needs to be understood is that the provinces, as the revenue generating units, want full control over the HEC budget and spending priorities. This is a fair demand given that we have a decentralised governance framework and the National Finance Commission Award of 2010 has increased the provincial shares in national revenues. It would be senseless for a body such as the HEC to fund laboratories in universities from Islamabad when education is a provincial subject. Therefore, we need to separate the two issues: the regulatory powers of the HEC which determine quality control, and the actual execution of ‘schemes’ to use the favored parlance of Pakistan’s public sector development process. Therefore, we have three aspects to address: a) standard-setting and quality control; b) foreign education and aid management; and c) physical works and improvements in the facilities within universities.

The way:

The Council of Common Interests (CCI) formulates the policy in part II of the Federal Legislative List contained in the Fourth Schedule of the Constitution as amended in 2010. Section 7 of this list states that “coordination of scientific and technological research” is a federal function. Similarly, section 12 is clear that the federation is also empowered to set “standards in institutions for higher education and research, scientific and technical institutions” along with ‘education’ with respect to “Pakistani students in foreign countries and foreign students in Pakistan” (sec 17). Thus, the ultimate arbiter of this issue is the Council of Common Interests — the apex mechanism in the Constitution, which mediates federal relations.

Given this clear prescription in the Constitution, the HEC devolution can be phased in a manner in which functions such as quality assurance, foreign scholarships, and donor-financed programmes ought to be retained under federal control. All other functions can swiftly be devolved to the provinces, as the momentum to change Pakistan’s governance cannot be halted. This is a rare opportunity, which cannot be squandered. Therefore, an amended, rationalised HEC needs to stay in place.

Learning from past mistakes:

A major wave of devolution came about in the wake of Musharraf’s devolution reform in 2001-2002. Admittedly, that was done in haste under a particular authoritarian agenda, but there are lessons inherent in this experience. Overnight transition did not work out well as the districts and tehsils did not have required capacities or resources; and often faltered in discharging their functions under the new governance architecture. We are not known for managing change as it is induced through military ‘revolutions’, executive diktats and foreign advisories. Managing change is a sophisticated process that needs to be carefully deliberated and planned. The HEC is no exception. All of its good work, notwithstanding many failures, cannot be undone in one stroke. A hasty devolution will result in a crisis of sorts as the provinces are not yet ready with the requisite capacities to manage universities and deal with specialised problems that are associated with such oversight.

Which way now?

The way forward therefore, comprises four major steps. First, the unbundling of HEC mandates and functions needs to take place and considered by CCI as well as the implementation commission tasked with devolution of powers to the provinces. Second, regulatory and policy issues need to be kept federal in a single institution instead of diffusing them to the Cabinet Division (validating degrees), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (international scholarships) and Ministry of Inter-provincial coordination (administration of the National College of the Arts), which would read like a recipe for disaster. These federal ministries have generalist cadres of civil servants whose record of handling their normal work routines is unenviable to say the least.

Thirdly, to fulfill the demands of constitutional governance, the budgets and projects can be transferred to the provinces, which have sufficient capacities to handle physical works and even management through their higher education departments or wings. Lastly, a detailed programme for capacity assessment and development with the provinces needs to be designed immediately and implemented in the next 12 months whereby, some of the regulatory functions can be handed over to the provinces by April 2012. Thereafter, a smaller and more efficient HEC can operate under the Cabinet Division carrying out the essential standard setting, internal and external coordination and quality assurance and monitoring functions.

The writer is a policy adviser based in Lahore. He blogs at www.razarumi.com and manages webzines Pak Tea House and Lahore Nama Email: razarumi@gmail.com

Source :http://www.jang.com.pk/thenews/apr2011-weekly/nos-10-04-2011/pol1.htm#1