A year ago, it was hoped that Pakistan’s democratic transition was proceeding in the right direction: one elected government followed by another, a free media, an independent judiciary and a military reviewing its past policy of interventionism. Obviously, such a situation imparted hope for policy revisions and course correction. Most importantly, given the nature of Sharif’s support base, the promise of economic revival seemed realistic.

Our structural constraints and the dwindling quality of leadership have come to haunt us again. So, within a year, the political future looks uncertain; and in such a situation, the scope for deliberated policy reform becomes even more limited. The federal government has been battling for its survival since June and its capacity for democratic negotiation is almost absent. While the apparent cause for instability is lack of consensus on election results and mythical charges of rigging, the underlying factors are deeper and more worrying.

True that the electoral system is hostage to systemic irregularities, manipulation, excessive use of shady financing and patron-client networks. That the traditional political elite have little incentive to reform is also a given. But there is larger crisis brewing in a fast urbanising Pakistan. And that relates to the absence of state writ, public services and an uncertain future for its younger population. All of this has bred impatience and disgruntlement with democracy. If the fruits of participation in the political process are not visible or realised, this is not too surprising.

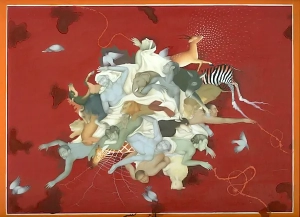

The inability to learn from our history-or the writing on the wall-drifts us further to the abyss

Imagine that we still have 25 million (nearly half of schoolgoing) children between the ages of five and 16 out of school. Pakistan ranks 146th among the 187 countries listed on the UN’s Human Development Index and according the multidimensional poverty count, 52 per cent of the population is estimated to be poor. Since 2008, there are no elected local governments and there is least amount of will to institute local democratic structures. For the average citizen, this does not inspire confidence in the state. Mega projects, such as metro buses and highways notwithstanding their importance, do not address the immediate needs of basic education and health.

The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution ratified in 2010 was the first step towards devolution of power. The overgrown provincial governments, managed largely by politically servile, unaccountable bureaucrats were to be realigned to the imperatives of devolution. That has happened in a haphazard manner; and most critically, the key powers and functions have not been devolved to the local level. Instead, the provinces want to amass more power, giving the respective political parties and coalitions more funds and leverage to dole out patronage to the interest groups, which gather votes for them and finance political mobilisation before and after the elections. These patterns will only change over time and the current drive for electoral reforms by the opposition is welcome except that it may just end up throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Estimates suggest that half of Pakistan’s youth population a heterogeneous construct is illiterate. Their sources of education, therefore, come from mosques, broadcast media and workplace experience. The rest has been influenced by what is taught in schools and madrassas. Until a few years ago, when some of the textbooks were revised, the education system had little emphasis on citizenship, and ideological indoctrination remained the express goal of curricula design. This is why, constitutionalism and the role of Parliament finds little resonance with the younger population.

The conduct of the elected is also not too encouraging. The current prime minister was criticised for not attending Parliament. Such is the nature of current political contest that Parliament appears to be largely irrelevant. The task of making it into a robust platform for public participation lies on the political parties. The standing committees started to function late. Similarly, there has been no discussion on the reports that measure progress against principles of policy outlined in the Constitution or that of proceedings of the Council of Common Interest a constitutional body that mediates federal and provincial interests.

Pakistan’s theocratic establishment, sections of which are armed, continues to disparage democracy. In cities such as Lahore, rickshaws bear messages that cite democracy as a system designed by the Zionists, a conspiracy to undermine the idea of a caliphate. Religious sermons and printed literature widely circulated feed into this narrative. For from the madrassa graduate to the urban youth, democracy, therefore, is a suspect project.

In this climate, it is easy to direct political mobilisation towards overthrowing the system and effect change that may or may not be in line with the Constitution. Once again, technocrats are being recommended as a panacea for the current political standoff. Such a milieu also provides an opportunity for unelected institutions to intervene to consolidate their power amid wrangling political parties. It seems that the consensus on how to govern Pakistan is still a work-in-progress. The only problem here is that 67 years is way too long a period for a country to figure that out.

The chaos that now grips the country successfully deflects the attention from the existential threats that we face. It is truly a poor reflection on the leadership we have that finds it far more important to agitate over or defend (through undemocratic crackdowns) the allegations of rigging than the massacre of Pakistanis, which we have witnessed in the past decade.

Beyond the anatomy of the current mayhem, there is an obvious case of losing direction. Which way are we headed and how are we going to shape the future for millions of young men and women of Pakistan. The inability to learn from our history or the writing on the wall drifts us further to the abyss.