As we celebrate the 70th anniversary of Pakistan’s creation, it is important to revisit the key questions that have befuddled the country. What is Pakistan’s identity? Can a larger Pakistani identity subsume the other identities of its citizens? Is it a nation-state or a state-nation? These vital quandaries have remained ever-present through the country’s history, and perhaps even before. It is critical that these be addressed for future direction.

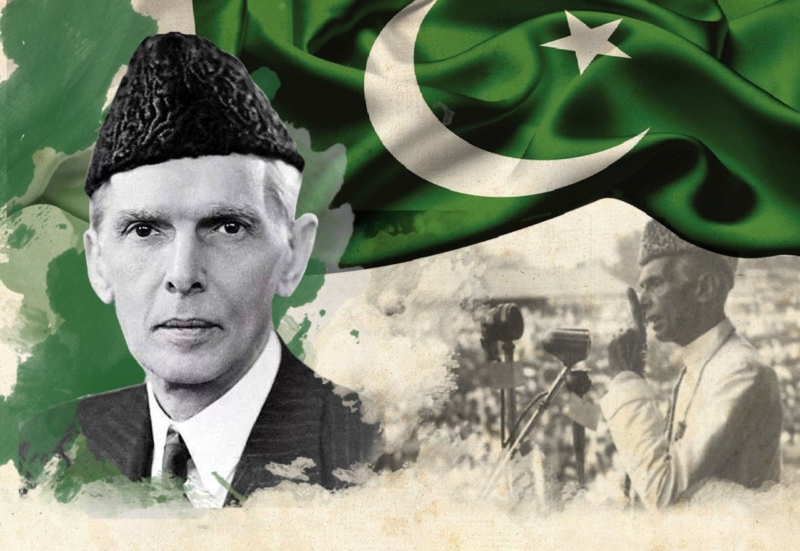

Seventy years are a sufficient time period to determine the contours of nationhood and build consensus around such issues. Yet, we seem to struggle with some of these quandaries. A key reason for this is divergence from Jinnah’s vision — a vision that was neither didactic nor dogmatic and evolved as he argued the case for Pakistan in the 1940s. There is no question that Jinnah invoked religious identity as the marker of a separate nationhood. The political context also demanded this, given that Gandhi had effectively introduced religious idiom in Indian nationalist politics. India was and remains a country where religion is enmeshed with culture and politics. The religious separateness of the Muslim community had wider political and economic issues of minority status in postcolonial India. The Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 with a weak centre and strong federating units with autonomy presented a workable way to keep India united and safeguard the interests of Muslim majority provinces. It failed and so did the prospects for a united India.

Jinnah’s struggle was centered on India’s minority question — a question that uncannily persists in 2017, too. Pakistan was meant to be the solution. But the idea of a nationalism anchored in religion as it evolved over decades has left minorities marginalised and at times hapless victims of violence

Once Pakistan was inevitable, Jinnah’s vision for the new state began to crystallise: a clear expression of this was his August 11 speech which underscored social justice, minority rights and no religious identity of the state despite its Muslim majority population. In the eleven months he lived, Jinnah also spoke about the neutrality of the civil service and civilian supremacy over the armed forces. The most critical policy direction he articulated pertained to relationship with India citing the US-Canada association as a model. Jinnah kept his Bombay home, inquired about its upkeep and saw it as a post-retirement place to visit. Would he have kept that house if India were to be the permanent and all-weather enemy of Pakistan?

He objected to the cover of TIME magazine sent by its editor for an autograph. The cover showed Jinnah as a Muslim tiger eating the Hindu cow. He returned the copies of the magazine, writing: “As I think the description ‘Mohamed Ali Jinnah, His Muslim tiger wants to eat the Hindu cow’ is offensive to the sentiments of the Hindu community, I cannot put my autograph on the cover page of the TIME magazine as requested by you.”

The story of Pakistan tells a different story: officialdom such as the powerful civil-military establishment, opportunistic politicians and a rudderless intelligentsia, took the country into an altogether different direction. The debates of the Constituent Assembly, which ended in 1956, are hauntingly relevant even today. By the time the country was a decade old, it was under martial law, had waged war with India, adopted a semi-theocratic objectives resolution; and appointed historians to write a new history denying Pakistan’s pre-1947 past.

Jinnah had expressly stated: “Do not forget that the armed forces are the servants of the people. You do not make national policy; it is we, the civilians, who decide these issues and it is your duty to carry out these tasks with which you are entrusted.” The 1958, 1977 and 1999 coups narrate a different story.

Thus the ideal Pakistani imagined by the state had to be delinked from the past, a caricature of a South Asian and upholder of the security state which had come into being. This is why we ended up as a State-Nation. Fatima Jinnah, a founder of the country, who challenged this security-centric and autocratic idea of nationhood, was termed an Indian agent.

Ethnic identities were also undermined at the expense of a broader national identity. The most tragic example of this phenomenon was the treatment of Bengalis culminating in the 1971 war and creation of Bangladesh. We endlessly complain about Indian interference, which was certainly there, but overlook that Pakistan reduced multiple identities of its citizens and groups.

Jinnah’s struggle was centered on India’s minority question — a question that uncannily persists in 2017, too. Pakistan was meant to be the solution. But the idea of a nationalism anchored in religion as it evolved over decades has left minorities marginalised and at times hapless victims of violence. This includes minority Muslim sects too. Non-Muslims are barred from holding the office of President or Prime Minister. Pakistan’s first cabinet had Hindu and Ahmadi members. Jinnah — a Shia-Ismaili — belonged to the minority Muslim sect. In 2017, the constitutional equality of citizenship is negated by the same document, and associated legislation. And the Shias have been at the receiving end of lethal militias. In 2017, the constitutional equality of citizenship is negated by the same document, and associated legislation.

Yet, the picture is not all bleak. Pakistanis have participated in three major popular movements for democracy; and never given in to authoritarianism. Most political parties want to change the security paradigm and move to an altered set of relationships in the neighbourhood. The 2010 amendments to the Constitution resulted in historic devolution of powers to the provinces for the first time in the country’s history. More importantly, even rightwing political parties have realised the perils of nurturing extremist ideas and improving the status of minorities. Legislative work by two Parliaments since 2008 has been momentous. Social transformation in terms of women and minority rights, decentralisation and federalism will be more pronounced in decades to come. But this will require staying the course by the democratic forces in the country.

Pakistan of 2017 is a different polity than before. The country has never been so young and bursting with creative energies; and never has been there a more noticeable consensus on democratic governance. At the same time, the unfortunate legacy of past decades haunts the country; and threatens the march forward. Pakistan’s youth will have to seize the moment and complete the stalled project of nation-building. A nation that respects diversity, celebrates it’s past, and locates itself in South Asia. A nation-state that ensures citizen equality, socioeconomic justice and securing regional peace. This will be Jinnah’s Pakistan, once it has been retrieved from the debris of autocracy, conflict and bigotry.

Published in Daily Times, August 20, 2017: In search of Jinnah’s Pakistan