In referencing N M Rashed, clay pots, paper boats, the river Ravi and the lost garment Saddri, Pakistani artist Sabah Husain creates a seamless whole out of seemingly disparate objects.

Sabah Husain, the accomplished artist of Pakistan, is a trendsetter. Currently affiliated with the School of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Sabah displayed her recent works in Washington DC where the Pakistani Embassy showcased her works for art lovers in town and also reiterated how important cultural diplomacy is for our missions abroad.

As someone who has followed Sabah’s work for some time, I have always been intrigued by her fusion of Pakistan’s rich literary and cultural traditions into her oeuvre of printmaking and paperwork. The exhibition entitled Mapping Waters (January 22-27, 2015) presented a range of paintings, prints and photography.

Four distinct, yet interwoven, sensibilities were curated at the exhibition: first, Sabah’s enduring conversation with Urdu’s best known modern poet Noon Meem Rashid and his epic poem Hassan Koozagar Ke Naam; the second layer invoked her interpretations of the once popular but now in virtual disuse saddri (men’s waistcoat with Central Asian origins); the paper boat; and Lahore’s dying River Ravi. At the outset these layers may appear to be incompatible but essentially they represent non-linear, complex journeys of an artistic vision.

In his celebrated poem, Rashed identifies himself with Hassan the koozagar (the potter). In material terms most ancient civilizations display pottery as both a daily convenience as well as an expression of the collective creative spirit. At a metaphysical level, clay symbolizes the material for creation shaped by the creator. Thus all three are one in the Sufi parlance of Wahdut ul Wajud (Unity of Being) and best represented by the famous line from Jalaluddin Rumi:

Khud Kooza O, Khud Kooza Gar O, Khud Gil-e-Kooz; Khud Rind O Subu Kush; Khud Bar Sar-e-Aan Kooza Kharidaar; Bar Amad Ba Shikast O Ravaan Shu.

He the vessel, its creator and also its clay;

He is the reveller drinking from it

And is the one who buys it and breaks the vessel having drunk from it

The mythical Hassan from Rashed’s poem was a resident of Baghdad and invoked during his long soliloquy, the banks of River Tigris, the boat and the powers of his creativity, poverty and longing. The poem also reminds us of the cycles of personal and civilizational growth and decay. Sabah interprets the poem and its metaphors the river and the boat and locates them in contemporary settings. This is where it all comes together: the poet and the artist both identify with Hassan who on the banks of a River muses on Time and its various manifestations. One such manifestation for Hassan’s successor, Sabah Husain, is the forlorn piece of garment Saddri (Sabah in a conversation told me that she owns and wears them too).

The mythical Hassan from Rashed’s poem was a resident of Baghdad and invoked during his long soliloquy, the banks of River Tigris.

Dr. Marcella Sirhandi, Emerita, Oklahoma State University, who was present at the exhibition, views the ubiquitous clay pots in Sabah’s work as symbolic receptacles of accumulated knowledge. Sirhandi adds that in Sabah’s series, the pots function beyond their common purpose. They hold and withhold and, like the paper boats, transverse alternative realities. A clay vessel morphs from one to many, from realistic to abstract and ultimately transforms into a double helix, the DNA of all knowledge.

Similarly, the saddri motif is both personal and civilisational. The garment was popular until the early twentieth century. Widely used earlier, it is now a fading cultural relic. Handwoven and intimate, it reflects the signature identity of its owner. Its variations were also used by Sufis and were passed on to the disciples much like the robe and topi (cap) as a sign of travelling knowledge and Sufi’s light.

I spotted saddris in rural Punjab when in my past life as a civil servant I was posted in the field. I have a faint remembrance of my maternal grandfather wearing one. A fakir on the banks of Nala Palkhoo that passed through Wazirabad (where I lived for a few years as an assistant commissioner) was always wearing one. The fakir was a travelling dervish and was usually silent. I used to see him every morning when I would go for a morning run.

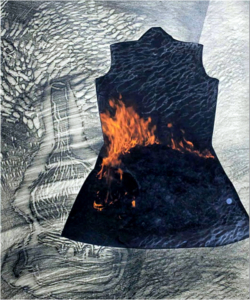

It shows fires of Partition that burned Lahore viewed from the banks of the Ravi late at night

As a time travelling tradition and piece of the self, Sabah interprets Saddri in multiple ways. In Light upon Light it is on fire. Perhaps as interpreted by Dr Sirhindi, it shows fires of Partition that burned Lahore viewed from the banks of the Ravi late at night. But the painting reminded me of Noon Meem Rashed again:

tamanna ki wus at ki kis ko Khabar he, Jahanzad, lekin

tu chahe to maiN phir palaT jaooN un apne mehjoor koozoN ki jaanib

gil o laa ke sookhe taGhaaroN ki jaanib

ma eeshat ke izhaar e fan ke sahaaroN ki jaanib

ke maiN us gil o laa se, us rang o roGhan

se phir wo sharaare nikaalooN k jin se

diloN ke Kharaabe hoN roshan!

If you want, I will go back to my forsaken pots

To the dried-out vats of clay-and-nothing

To the props of my life, my art

So from this clay-and-nothing, color and oil glaze, I

Can again strike sparks

That light up the ruins of hearts.

(translation by Frances Pritchett)

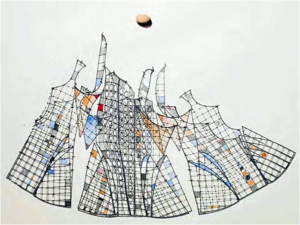

In the painting Khod Kooza o Khod Kooza gar the saddri merges with the pots as vessels of generational knowledge, experience and starts resembling DNA structures.

Sabah’s works with boats are incredibly inventive. Once again using it as the metaphor for inner journeys, the boat appears in her richly textured prints. In the series Mapping Waters, Sabah creates prints through handmade paper and photographic ink that seeps into the pores of the material, giving the image a peculiar hue, almost a new existence like what the eternal potter would do to the clay. Once again, the potter from Rashed’s poem is present in these memory-scapes:

wo kashti, wo mallaah ki band aankheN

kisi Khasta-jaaN, ranj bar kooza gar ke liye

aik hi raat wo kahrubaa thi

ke jis se abhi tak he paiwast us kaa wajood

us kaa paikar

magar aik hi raat kaa zauq darya ki wo lehr nikla

Hasan koozagar jis meN Dooba to ubhraa nahin hai!

That boat, the boatman’s closed eyes

For a worn-out, grief-burdened potter

One night was the charged amber

His static being clings to, even now.

His soul, his shape

But that night’s flavor was a river-wave in which

Hasan the Potter sank and has not come up. (trans. F. Pritchett)

Mapping Waters featured paper boats made from drawings and prints from her portfolio that have not been displayed earlier. These boats like the koozas are cut and folded into vessels that can take aquatic journeys. The handmade paper that Sabah uses creates ripples and waves of a turbulent current in the words of Dr Sirhindi, thereby adding another dimension to the dreamy artistic expression.

This series employs myriad metaphors of river, boats, clay pots and shores to create the effect of Sabah’s personal artistic journey that in effect is a subset of the larger human experience from the romanticised ancient to the turbulent present. The banks of the river reflect both decay and renewal. Sabah’s inspiration for the river representations also comes from a poem on Ravi by an unknown poet:

Haan aye lab e Ravi bataa

Kuch raftagaan kaa majra

Kal tujh pe jin ka raaj thaa

Anjam un ka kiya hua

Pray tell us, O bank of Ravi

Tales of the past

Those who ruled here

What happened to them?

Lahore’s river Ravi was the nourisher of the city since ancient times. The later development of the present walled city as well as the Fort were located close to it. The River kept on changing its course thus enabling expansion of the urban settlements. Now it is dry for most of the months due to the water-sharing arrangements with India under the Indus Water Treaty. In addition, Ravi has been polluted with sewage, toxic waste etc. due to the population explosion that took place in the last five decades or so. So the River in its present shape is both a sign of the past and the decrepit present. As noted above, this connects the artist with the memory of Tigris; and much like the elusive Hassan, the narrator-artist continues the eternal creative spirit. Koozas here turn into paper boats that also play with the collective, precious childhood memory of the quest for travel.

Sabah Husain’s training in Kyoto University of Fine Arts and Music has given her the requisite training to treat as well as create newer, personal forms of paper. Sabah’s journeys are also reflected in the material she uses. From Baghdad to Ravi and from Kyoto to Lahore and Boston, her work encompasses a quest for confronting Time as a repository of memory and a window to the future.

In Mapping Waters, handmade paper, prints, mixed media, and photography converse with all the conceptual, metaphorical layers. The variety of inventive techniques used are transmigrations in their own right. This is why the texture of Sabah’s work is unique for its crafted, eclectic diversity.