Pakistan’s Supreme Court has upheld the death penalty for Mumtaz Qadri “the policeman who murdered former Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer in January 2011 for an alleged act of blasphemy”. I analysed the implications.

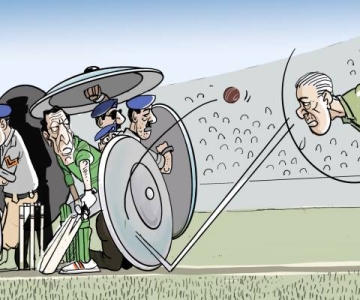

The Supreme Court of Pakistan on 7 October upheld the decision of the trial court and the Islamabad High Court and rejected the appeal against Mumtaz Qadri’s death sentence. The defence lawyers had argued that because the slain governor Salmaan Taseer termed the blasphemy laws as black laws, Mumtaz Qadri had the right to kill him.

The obiter dicta from the bench, as reported in the press, were also encouraging. Supreme Court Justice Asif Saeed Khosa, while discussing the case, remarked that criticizing blasphemy laws does not amount to committing blasphemy and that Mumtaz Qadri had no legal grounds to take the law into his own hands. The fact that such a remark clarifying that questioning the blasphemy law is not blasphemy becomes a cause for celebration says quite a lot about the socio-cultural milieu of Pakistan. Similarly, it is highly unlikely that the apex court would have actually bought into the sham arguments presented by the defence lawyers and overlooked the rather clear admission of the accused.

The idea of committing violence as a religious obligation is neither alien nor criminal for a sizeable number of people

However, the temporary euphoria after this judgment must not conceal the fact that a former Chief Justice of Lahore High Court and a former judge of the same court were defending the accused largely on theological grounds. In fact the former judge, Justice Mian Nazir Akhtar, in an interview declared that disliking ‘kadoo’ (pumpkin) was akin to committing blasphemy, since that was a vegetable preferred by our Holy Prophet (PBUH). While the verdict is an important step to establish rule of law, the lawyers who showered rose petals on Mumtaz Qadri will not disappear nor will young students who vandalized a vigil for Salmaan Taseer earlier this year.

Social media gives (admittedly partial) insight into how the issue of blasphemy is viewed and understood by a large number of people in our society. The idea of committing violence as a religious obligation is neither alien nor criminal for a sizeable number of people. It has travelled through years and manifests itself in popular culture and its various expressions. Its best expression is the heroic stature of Ghazi Ilam Din Shaheed.

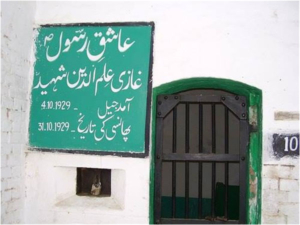

Towards the end of Margalla Road in Islamabad lies the Foreign Service Hostel . It is a drab, concrete modernist structure. And, it is named after Ghazi Ilm Din Shaheed, an early hero of South Asian Muslim consciousness. Ilam Din is both a Ghazi (a surviving warrior) and a Shaheed (martyr) in our cultural memory that has been reinforced and officially sanctioned by the state. For the Foreign Ministry to name its officers residence after Ilam Din is a reminder of how heroes have been adopted and to some extent mythologized by the state of Pakistan.

. It is a drab, concrete modernist structure. And, it is named after Ghazi Ilm Din Shaheed, an early hero of South Asian Muslim consciousness. Ilam Din is both a Ghazi (a surviving warrior) and a Shaheed (martyr) in our cultural memory that has been reinforced and officially sanctioned by the state. For the Foreign Ministry to name its officers residence after Ilam Din is a reminder of how heroes have been adopted and to some extent mythologized by the state of Pakistan.

On the 6th of April 1929, Ilam Din, a young carpenter from Lahore, murdered a blasphemer Rajpal “ a Hindu by faith“ for publishing an allegedly offensive pamphlet against the Prophet (PBUH). Rajpal published the ostensibly distasteful material in 1924, five years before his murder. He was booked under the Indian Penal Code but was acquitted by the Lahore High Court in May 1927.

This trial took place in the context of communal tensions that had been brewing under British rule. Ilam Din was sentenced and for his appeal, Mr Mohamed Ali Jinnah (later to become the founder of Pakistan) appeared in the High Court as a defence lawyer. The appeal was rejected. Another appeal to the Privy Council was also rejected and finally Ilam Din was hanged in 1929. The mythmaking began thereafter and in the years to come Ilam Din was portrayed as a grand hero of Muslim community: a true one, because he was successful in meting out the punishment that the earlier ones could not achieve. In fact, Ilam Din remained unaware of the printed book for years and only through fiery speeches in Lahore did he find out about its insulting content.

The funeral of Ilam Din was also a spectacle. Noted Muslim celebrities of the age participated. Allama Iqbal, our national poet was present and reportedly said that a carpenters son was superior to others for having defended the faith

The funeral of Ilam Din was also a spectacle. Noted Muslim celebrities of the age participated. Allama Iqbal, our national poet was present and reportedly said that a carpenters son was superior to others for having defended the faith. Similarly, another poet-intellectual of that era, MD Taseer was sympathetic to Ilam Din. Nothing can be more ironic as decades later, Taseer’s only son Salmaan Taseer was killed for a false accusation of blasphemy.

In our textbooks, the character of Ilam Din is celebrated. As an ideological state the imperative to highlight such cases is understandable. Ilam Din is also a symbolic warrior-hero pitted against a Hindu offender. Rajpal in cultural memory therefore becomes a representative of what Pakistan liberated itself from.

In popular cinema, a 1978 film Ghazi Ilam Din Shaheed also played upon the myth of the hero who burns with the desire for martyrdom. The film also showed Mr Jinnah (who has been another object of re-branding after his death) as somewhat sympathetic to the cause and if I recall correctly refuses to accept fees for the case. The finale suggests that the Hindus and Muslims could not have lived together. Whatever was written earlier about Ilam Din in Urdu suggested that not just the religious dimension but popular cinema also reinforced the pre-partition politics and the communal tension, which culminated in the partition of India in 1947.

Now Ilam Din’s grave is a shrine, a sacred space that commemorates his sacrifice as well as evokes the nationalist narrative of an insensitive British justice system and the acts of anti-Muslim Hindus that led to the Partition.

The hanging of Mumtaz Qadri “a single culprit” may deliver justice in a narrow sense but to create a tolerant and humanistic society we have to start thinking of delinking religion from statehood

The notion and legal punishment for blasphemy are located in our colonial experience. After 1947, it was duly extended and appropriated by the state for ideological purposes. This is why it has become more and more stringent over the years especially since the Zia era. Nawaz Sharif in his first term as PM made it more draconian apparently with the blessings and intervention of his deceased father. The law also becomes a means to incite passion, earn political mileage and in some cases fix anti-state elements. Let us not forget that in 2014, a TV channel was booked under the law immediately after its seditious posturing.

Pakistan needs an open debate about its identity and future. As long as the state narrative creates the binary of an Islamic fortress pitted against the outsider-infidel, we are likely to reproduce Mumtaz Qadris. The last public blood-fest (over a silly online film) carried out in 2012, was partially enabled by an ostensibly liberal government to appease religious passions. Ghulam Ahmed Bilour of the Awami National Party (ANP), a secular politician, announced a $100,000 reward for anyone who killed the blasphemous filmmaker. He continues with such gimmickry despite the fact that his brother was killed by the Taliban!

The hanging of Mumtaz Qadri “a single culprit” may deliver justice in a narrow sense but to create a tolerant and humanistic society we have to start thinking of delinking religion from statehood. Are we willing to give up some of the heroes that are celebrated in the land of the pure? Is the Parliament ready to debate the misuse of blasphemy laws? Until that happens, the enthusiastic commentators who see the recent judgment of the Supreme Court as a point of departure may need to reconsider their position.

1 Comment