Finally, I wrote a piece on Delhi ……

Delhi’s present day chaos cannot belittle its grand past, which created a civilisation and shaped the contours of Indo-Muslim identity

When travels come, they come in battalions. Such has been the trajectory of my recent sojourns to Delhi. Travel to India can be, at best, random and left to a game of chance, given how the officialdom on both sides of the border ensures that people don’t cross real and imagined boundaries. Coincidence, or as my less rational side would say, the calling of the Delhi and Ajmer Saints, enabled me to land in Delhi twice in less than three months.

When travels come, they come in battalions. Such has been the trajectory of my recent sojourns to Delhi. Travel to India can be, at best, random and left to a game of chance, given how the officialdom on both sides of the border ensures that people don’t cross real and imagined boundaries. Coincidence, or as my less rational side would say, the calling of the Delhi and Ajmer Saints, enabled me to land in Delhi twice in less than three months.

My most recent visit is in some measure courtesy of TFT. My obituary on Urdu’s towering writer Qurratulain Hyder in TFT last August was read by the immensely talented Rakshanda Jalil, media coordinator at Jamia Millia Islamia. A few months later she sent me an invitation to talk and present a paper at a seminar on the legacy of Qurratulain Hyder. There was no way that I could have refused this invite. Ms Hyder is my all time favourite writer; Delhi, an incomparable city to visit; and above all the opportunity to explore Jamia, a historical seat of learning associated with luminaries such as Maulana Azad and Dr Zakir Hussain could not be missed.

Delhi is not an ordinary South Asian metropolis. Its present day chaos cannot belittle its grand past, which created a civilisation and shaped the contours of Indo-Muslim identity, nourished the Urdu language, produced the finest verse in Hindustani and Urdu and fashioned a fabulous architectural legacy. This is why Delhi fascinates me endlessly. Each time I visit, I find a mohallah of the old dilli that concerns an important event or personality. Even better, another hitherto unknown monument is introduced to me; it is like a newly discovered continuation of an enjoyable book. One has only to casually drive around the city to find that it is dotted with monuments. I cannot complain that they are neglected in India; considering that Pakistan’s mighty administrators erect Shaminaas on Mughal monuments for personal parties, how can one grumble about the infidel neighbours!

Delhi is not an ordinary South Asian metropolis. Its present day chaos cannot belittle its grand past, which created a civilisation and shaped the contours of Indo-Muslim identity, nourished the Urdu language, produced the finest verse in Hindustani and Urdu and fashioned a fabulous architectural legacy. This is why Delhi fascinates me endlessly. Each time I visit, I find a mohallah of the old dilli that concerns an important event or personality. Even better, another hitherto unknown monument is introduced to me; it is like a newly discovered continuation of an enjoyable book. One has only to casually drive around the city to find that it is dotted with monuments. I cannot complain that they are neglected in India; considering that Pakistan’s mighty administrators erect Shaminaas on Mughal monuments for personal parties, how can one grumble about the infidel neighbours!

But Delhi is not a city of the dead and tombstones only. It is a mega-city alive with countless sub-cultures, languages and religions converging and conflicting at once. The partition has made Delhi into a hub for Punjabi immigrants as well, bringing a new dimension to the culture‚ not to mention hippie haunts such as Pahar Ganj or the hip Hauz Khas that boast art, fashion and contemporary sensibilities. However, all of this does not do much for me. I’d rather be elsewhere for contemporary sounds and flavours.

My Delhi is the Delhi of the Khawajas, the Mughals and the present day secular Indians – Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs‚ who respect the separate identity of Pakistan and are willing to befriend a Pakistani bloke without reminding him ad nauseam that his country is an artificial construct, a blot on the soul of mother India. For me, Delhi is the fascinating mix of places I love to visit and a handful of people who are warm and intelligent, profound, often unassuming and otherwise extraordinary in so many ways.

The Nizamuddin neighbourhood, close to the shrine of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and a medieval settlement, is my microcosm of Delhi. Despite the exponential increase in the population, this area retains an ambiance that narrates the changing seasons of history. There are numerous monuments scattered around the area and it’s a splendid feeling to buy a phone card while standing next to Humayun’s tomb or pick up flowers in front of a medieval noble’s tomb. Not to mention that each time you cross the road, you’re crossing a few 700-year-old structures. The drama, poetry and poignancy of the setting cannot be missed.

As you walk under the shade of old trees from the Nizamuddin East towards the shrine in the western side of the settlement, the antidote to affluent gated communities merges into the palpable reality of Muslim ghettoisation. The old bastee of Nizamuddin houses a community that has withdrawn into itself and is reeling under a psychological siege, closing its ranks to the outside world‚ including modernity and education. Nevertheless, I love the bastee as it reminds me of old Lahore. But here the moods of old Lahore have Ghalib’s tomb, footsteps of Amir Khusrau and the spellbinding aura of Nizamuddin Auliya’s shrine.

As you walk under the shade of old trees from the Nizamuddin East towards the shrine in the western side of the settlement, the antidote to affluent gated communities merges into the palpable reality of Muslim ghettoisation. The old bastee of Nizamuddin houses a community that has withdrawn into itself and is reeling under a psychological siege, closing its ranks to the outside world‚ including modernity and education. Nevertheless, I love the bastee as it reminds me of old Lahore. But here the moods of old Lahore have Ghalib’s tomb, footsteps of Amir Khusrau and the spellbinding aura of Nizamuddin Auliya’s shrine.

After a quick halt at Ghalib’s lonesome tomb, I always stop at the Ghalib Academy, a low-key little organisation‚ next door to check if there are any new titles or scheduled gatherings. It is a separate matter that the wine loving Ghalib’s mazar now faces the Indian Tableeghi Jamaat’s main office in Delhi, where many brethren drunk on piety loiter about. This time I found Annemarie Schimmel’s A dance of sparks: Imagery of fire in Ghalib’s poetry at the Ghalib Academy for Rs 150. Books are published and read in India and affordable prices are a major incentive for the huge middle class readership.  And there are bookstores that can keep one entertained for days‚ old and new, light and heavy, from the banal to the highbrow.

And there are bookstores that can keep one entertained for days‚ old and new, light and heavy, from the banal to the highbrow.

One can walk into the medieval lanes of the bastee where all sorts of new-age healers have advertised their little spiritual shops. Not an unfamiliar sight, except that the setting is marvelous. Customarily, you need to pay respects to Amir Khusrau, inventor of the idiom that North India and Pakistan speak, before reaching Nizamuddin’s shrine. There are quite a few intermediaries out to make a quick buck and you can be stopped a few times to be initiated into a list of rituals that have to be performed, for money, of course. Luckily, I don’t go there alone and am hence typically saved of the hassle, but I have been through it a few times.

In the evenings, qawwals from far and wide perform on a regular basis. The courtyard turns into a captivating place with hundreds of people of all religions, castes and ethnicities participating and swooning in the mehfil. Unpretentious, earthy and undeniably real.

In the evenings, qawwals from far and wide perform on a regular basis. The courtyard turns into a captivating place with hundreds of people of all religions, castes and ethnicities participating and swooning in the mehfil. Unpretentious, earthy and undeniably real.

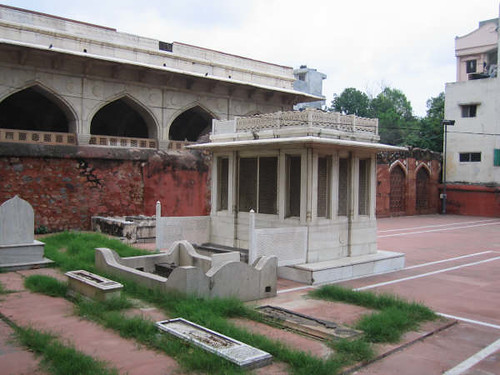

Nizamuddin’s compound houses the grave of Jahan Ara, the spirited daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan and sister of the eclectic prince Dara Shikoh. A devotee of the Sufis, Jahan Ara was a poet, a builder, a city planner and a woman of letters. Jahan Ara created the famous Chandni chowk, laying out the buildings, canals and a garden around it. Delhi was ruled and bejeweled by such fabulous characters. As for the present, let me cite an anecdote. My dear friend, Vidya Rao, a thumri singer par excellence, found her cat at Nizamuddin. She adopted the lost cat, named her “Sufi” for the dargah at which she was found and took her to her house, next to the shrine of H Bakhtiyaruddin Kaki.

The little compound at the shrine encapsulates eight centuries of history, empire, movements, musical innovations and poetic sensibilities that thrive even today. I have also recently discovered the Sufi Inayat Khan Centre, a hub for the international Sufi network, next to Nizamuddin dergah. This is a serene place with impressive facilities. As opposed to the common moorings of Nizamuddin, Inayat Khan Centre is more exclusive with many European and North American visitors staying or meditating in their little chambers. Music also holds a central position within the activities of Sufi Inayat Khan Centre.

Of course, this is merely a fraction of Delhi’s immense character. But this is how I like to spend my time there. Not unlike most cultural capitals, Delhi is abuzz with “events.” The exclusive India International Centre has become the fulcrum of literary and artistic events. It has a brilliant library and various places to meet, eat and chat. The little intellectual island within an endless city endears to residents and visitors alike.

A lot happens elsewhere too, in somewhat less lofty precincts. This December, I marched with a rally from Chandni Chowk to Ghalib’s Haveli in the famous Mohalla Balimaran. This procession was led by none other than the inimitable poet Gulzar who had flown from Bombay to attend the birthday celebrations of Mirza Ghalib. Such was the charisma of Gulzar that Delhi’s Chief Minister was just another guest at the event. Several Urdu wallahs , an endangered species in India, were also there in achkans, carrying their lost glory and forsaken dreams. Ghalib’s brilliant biographer Pavan Verma introduced me to Gulzar, and what an exciting moment that was. The Haveli was adorned for the occasion and the hip-hop reporters from the TV channels kept asking why Galib-ji was so great. In the post-ceremony mayhem, yours truly was also asked to speak. It was my first TV appearance‚ on Ghalib’s humanism, relevance and universal appeal. Not bad, I thought then. God knows how it appeared as I never got to see it.

A lot happens elsewhere too, in somewhat less lofty precincts. This December, I marched with a rally from Chandni Chowk to Ghalib’s Haveli in the famous Mohalla Balimaran. This procession was led by none other than the inimitable poet Gulzar who had flown from Bombay to attend the birthday celebrations of Mirza Ghalib. Such was the charisma of Gulzar that Delhi’s Chief Minister was just another guest at the event. Several Urdu wallahs , an endangered species in India, were also there in achkans, carrying their lost glory and forsaken dreams. Ghalib’s brilliant biographer Pavan Verma introduced me to Gulzar, and what an exciting moment that was. The Haveli was adorned for the occasion and the hip-hop reporters from the TV channels kept asking why Galib-ji was so great. In the post-ceremony mayhem, yours truly was also asked to speak. It was my first TV appearance‚ on Ghalib’s humanism, relevance and universal appeal. Not bad, I thought then. God knows how it appeared as I never got to see it.

Before Ghalib, Delhi was synonymous with Mir Taqi Mir and his timeless verse. The oft quoted couplets where Mir complains of Delhi’s destruction cited the city as Aalam mein Intikhaab, the chosen city of the world, ruined by the vagaries of time. I am glad that Mir Saheb is no more as he would have disapproved of what old Delhi has become‚ an inferno of a time-trapped Muslim underclass, where Urdu is evidently on the defensive.

Before Ghalib, Delhi was synonymous with Mir Taqi Mir and his timeless verse. The oft quoted couplets where Mir complains of Delhi’s destruction cited the city as Aalam mein Intikhaab, the chosen city of the world, ruined by the vagaries of time. I am glad that Mir Saheb is no more as he would have disapproved of what old Delhi has become‚ an inferno of a time-trapped Muslim underclass, where Urdu is evidently on the defensive.

Old Delhi, with the Jama Masjid as its landmark, intensely engages the visitor. The names of the streets haven’t changed and classic Delhi cuisine‚ nihari, kebabs and mutton mixes‚ is outstanding. The rickshaw pullers, vendors, beggars and the poor largely represent the local Muslim population. And now the Jamia Masjid might have a mall in the vicinity that land developers are keen to build and mosque administrators eager to support. At the end of the day, globalisation is all about getting rich, even if it means only a handful enjoys the fruits of “development.”

Sarmad the naked fakir was also a resident of Old Delhi and is buried there. Beheaded by Aurangzeb for being blasphemous, naked and defiant, Sarmad’s tomb is befittingly red and flaming. One has to visit the place to feel what mood it holds: it borders on the surreal. It was unlike anything that I had ever experienced.

As I mentioned earlier, during my last visit I was a guest at Jamia Millia Islamia for the seminar on Urdu writer Qurratulain Hyder’s legacy. Jamia retains its secular credentials but has expanded over time into a wide-ranging centre of graduate and post-graduate studies. India’s eminent historian Mushirul Hasan is Jamia’s current vice-chancellor and has consolidated Jamia into a formidable institution. Mushir is a prolific writer and quite an inspiring figure.

As I mentioned earlier, during my last visit I was a guest at Jamia Millia Islamia for the seminar on Urdu writer Qurratulain Hyder’s legacy. Jamia retains its secular credentials but has expanded over time into a wide-ranging centre of graduate and post-graduate studies. India’s eminent historian Mushirul Hasan is Jamia’s current vice-chancellor and has consolidated Jamia into a formidable institution. Mushir is a prolific writer and quite an inspiring figure.

My paper at Jamia dealt with the enigma of Hyder’s dual belonging and her popularity among Pakistani readers. She lived in India, but was immensely popular as she presented an alternative view of history and selfhood. Hyder remained a unique bond between India and Pakistan until she died. She was a regular visitor in Pakistan, her second home in actual terms. Her family, friends and admirers never distanced her from Pakistan. Like her characters, she travelled, migrated and re-migrated and became a chronicler of our times, not as a historian but as a fiction writer. I concluded my talk at Jamia with these words: “Hyder was truly a dual citizen in an age where acrimonies of Partition and officialdom have made it impossible to hold concurrent citizenships. But Qurratulain Hyder even defied that; and proved that, like her vision, her belonging could be concurrent and beyond the accepted definitions.”

Indeed that was possible only with the stature and immense talent of Ms Hyder. Lesser mortals will remain hostage to visas and textbook identities. My Delhi travels are enriching as they lead to a near-dissolution of the textbook enmities that we had grown up with as the grandchildren of Partition. It is this reclaiming of my pre-Pakistan, Muslim and syncretic history that makes Delhi an enchanting place for me. Each time I am there, I connect with the larger subcontinental canvas that exists beyond the accepted and myopic definitions of identity. This is why I am never bored in Delhi; as many Delhi wallahs can never bore of the charms of Pakistan.

First published in the Friday Times