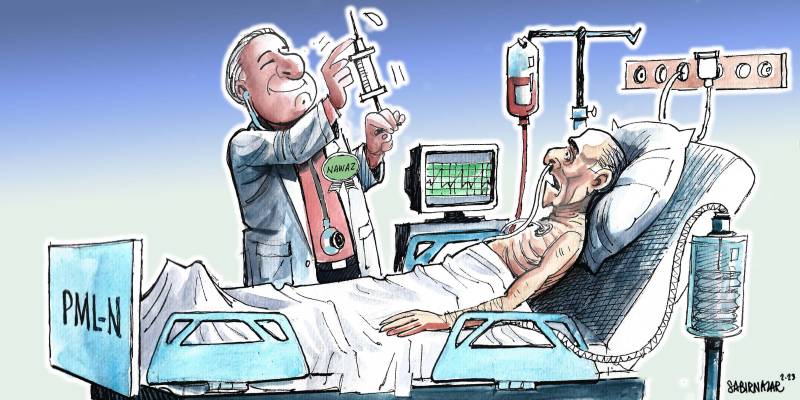

The electorate blames the PML-N for the inflation that’s making their lives difficult, and Imran Khan owns the anti-establishment narrative despite being locked up. With the party divided, there is no shortage of challenges that await Nawaz Sharif on his return.

In a widely expected move, former prime minister Nawaz Sharif has announced his return to Pakistan on October 21. This much-anticipated return completes a full circle of our recent turbulent history. The very same Sharif was hounded, fired, disqualified, jailed and later exiled only a few years ago. His strongest political foe is currently facing the same cycle, with a political future that remains uncertain. Such are the machinations of Pakistan’s all-powerful miltablishment and its long-time partner i.e., the superior judiciary.

The country that Nawaz Sharif is returning to has drastically changed in the past four years. Nawaz Sharif’s absence enabled Imran Khan to assume a central role in Pakistani politics and Khan’s populist rhetoric notwithstanding, he emerged as a legitimate national politician with considerable support across different regions and classes of Pakistan.

Millions of young Pakistanis have been registered as new voters, whose worldview has been shaped by the state narrative that Nawaz Sharif and his family are ‘corrupt’ and unfit to govern the county. Whatever anti-establishment bluster that Nawaz Sharif had articulated has vanished in thin air as the anti-establishment force of 2023 is the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). Perhaps the most critical variable is the dire economic condition of an average Pakistani across the class spectrum. With the inflation rate at 40% and mega devaluation of the Pakistani rupee, the status quo is an untenable situation for most households that cannot even afford to pay their electricity bills.

Popular surveys and media reports suggest that Pakistanis have all but forgotten the misgovernance under Imran Khan and they squarely blame Shehbaz Sharif for the inflation they are dealing with.

This is also an intensely polarized Pakistan, where the permanent institutions of the state are internally divided around the persona of Imran Khan.

In the short-term, Nawaz Sharif will have to face numerous legal challenges to emerge as a credible player in the electoral arena, but his trials are far greater this time due to the mistakes of his party in giving a free hand to the establishment, the inability to look beyond the dynasty and a reluctance to take on powerful economic interests during the seventeen months of Shehbaz Sharif’s rule. Popular surveys and media reports suggest that Pakistanis have all but forgotten the misgovernance under Imran Khan, and they squarely blame Shehbaz Sharif for the inflation they are dealing with.

How will Nawaz Sharif distance himself from the pliant PDM government that his brother ran for more than a year after Imran Khan’s ouster in a no-confidence vote.

If Nawaz takes a hard line on the establishment, his return to power will be throttled, and if he doesn’t do that, his support base will further dwindle in the coming months. The sentiment on the street remains anti-establishment, and ironically Nawaz remains a key contributor to this changed reality. In fact, Imran Khan only picked up the anti-establishment narrative from where Nawaz had left it. Khan took this political rhetoric beyond the confines of Pakistan, and today the Pakistani diaspora has completely bought into a worldview that holds the military responsible for the political turmoil and economic meltdown.

But even if Nawaz handles this problem, his party has also fallen victim to fissures from within. There is a Maryam Nawaz-led camp, which yearns for a Sharif brand that took on the military establishment in a quest for ‘civil supremacy.’ And then there is the Shehbaz-led camp, which happens to be the dominant group, that argues for a partnership with the generals to gain power and the ability to dole out patronage. Another camp, albeit smaller, comprises somewhat disgruntled party stalwarts like Shahid Khaqan Abbasi and Miftah Ismail, who were maltreated by brothers Sharifov.

If Nawaz takes a hard line on the establishment, his return to power will be throttled, and if he doesn’t do that, his support base will further dwindle in the coming months.

One significant outcome of the establishment’s heavy handedness has been the inability of the PML-N (and other parties) to organize. In the July 2022 by-elections, this weakness was witnessed by all and sundry when the PML-N couldn’t run a proper campaign in Punjab despite being in power. The party lost the political battle, boosting Imran Khan’s narrative of being the most popular politician in the largest province of the country.

Even if Nawaz Sharif manages to pull his party together, fix the internal groupings and create a new narrative, the ground situation should be a cause for major concern, and that is where the real challenge for PML-N lies.

Despite Imran Khan’s incarceration and efforts to diminish his party, the PTI remains a formidable electoral option for the urban, middle-class and young voters. Observers have commented that even if Imran Khan cannot campaign, his supporters will register their anger at his treatment through the ballot box. There is a precedent of the 1970 election, when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto enjoyed a similar following, especially in the Punjab province.

If the establishment comes to Sharif’s rescue, as some well-informed people are claiming, this would rob Nawaz’s electoral ‘victory’ of legitimacy and create another crisis for his party.

Despite Imran Khan’s incarceration and efforts to diminish his party, the PTI remains a formidable electoral option for urban, middle-class and young voters.

Lastly, the elephant in the room. While the brothers Sharifov confer in London, the incumbent Chief of Army Staff General Asim Munir has virtually taken over the reins of government. Not only is he fixing the value of the dollar, leading crackdowns on hoarders, smugglers and electricity theft, he has promised the nation of a $100-billion windfall from the Gulf countries through the SIFC. A military led Special Investment Facilitation Council is literally setting the future economic agenda for the country.

Where does Nawaz fit in this scheme of things? Will he enjoy popular support and the backing by political forces to rearrange the power cards? Will he be allowed to exercise the full powers of the Prime Minister’s office, something that he has been demanding for the last 33 years? The answers to all these questions are unknown.

However, the rapidly changing geopolitical scene might be aiding Sharif’s return. The Saudis, UAE and other Gulf countries partnering up with India is a clear message to their ‘brotherly’ client that normalisation with India will be a prerequisite for Pakistan’s bailout in the short to medium term. This may be the only chance for Nawaz Sharif to implement his three-decades-old vision of regional trade, economic cooperation and realigning Pakistan’s foreign policy. This could be the only reason that the generals might not object to his return to power. But even this shift in policy will be rocked by resistance within and public ire.

Nawaz Sharif’s journey back to Pakistan is the first step on the long, arduous road ahead for Pakistan.