Pakistan’s blasphemy law is used to fuel violence and death.

The recent murder of a brave human rights lawyer Rashid Rehman reminds us of the society we have shaped. It is now an unregulated space where even defending the rights of an accused is a crime. Rehman had made all the threats, including those in the courtroom, public. The local state authorities did next to nothing to protect him or rein in the individuals and groups preaching violence. It seems when it comes to religiously motivated violence the might of the state disappears. Victims of blasphemy law are no longer fit for due process. They need to be punished directly. A few days after the murder of Rehman, another accused of blasphemy was shot dead by a teenager in a police station near Lahore.

Since the brutal murder of Salmaan Taseer in January 2011, debates on the colonial blasphemy law have disappeared from the public domain. Those who advocated against its misuse were also silenced through litigation in courts by the right-wing lobbies that no longer constitute the lunatic fringe. In fact, the idea of blasphemy as a threat to Pakistan’s carefully constructed “Islamic” identity mixes passion, politics and power. A state that quietly smiles at the success of its project is now complicit in mob justice and even brutal killings such as the one that took Rashid Rehman’s life.

Fear and silence

Earlier in March, on the eve of Hindu festival Holi, an allegation of blasphemy against a local Hindu led to the attack on a community centre and a temple in the stronghold of liberal PPP (Pakistan Peoples Party) Larkana in Southern Pakistan. The scenes of vandalisation in Sindh province, otherwise known as the land of Sufis and where the largest number of the Hindu population lives, were chilling.

It is pointless to moan the response of the state officials who are content with terming such issues “sensitive” or in other words a no-go area carved in the public imagination. A report by Reuters states that March 2014 was the “worst month for attacks on Hindus in 20 years with five temples attacked, up from nine during the whole of 2013”.

Nearly a month ago, a Lahore court awarded death sentence to another alleged blasphemer, Sawan Masih, marking a new low in our legal and judicial system. A low income settlement in Lahore – Joseph Colony – was attacked in 2013 and nearly a hundred homes were torched. The mayhem was triggered by an ‘allegation’ of blasphemy. To give credit where it is due the Punjab government promptly helped in rebuilding these homes. However, its police and prosecution failed to nab those who were involved in this kind of “collective punishment”.

The ruling party even failed to take cognizance of the reported involvement of its local leader from the area. And the judicial system – trained in the curricula and discourse of Islamisation and deeply afraid – meted out a tough sentence to another Christian.

The Punjab based militant organisations according to reports maintain close surveillance of Christian settlements. The results of this activism have been witnessed in Gojra, Jospeh Colony and elsewhere. Collusion by political parties and inability of law enforcement agencies have led to a state of confusion and impunity.

Pakistan has the unique distinction of abusing the controversial blasphemy laws and according to a recent report (prior to Sawan’s sentence), 14 individuals were on death row on blasphemy convictions and 19 convicts were serving life sentences There are hundreds of others who have been arrested or charged with the crime. It is not the execution of a sentence but the fear and mob justice that comes in the wake of such charges. After Rehman’s murder, lawyers would think twice before taking such a case. Judges would be afraid to deliver verdicts and the police – already partisan – will further abandon its job.

After the sentencing of Sawan Masih, a few parliamentarians raised this issue in the national assembly but nothing changed. Outraged citizens protest, write op-eds in the English press and few reckless types like me, who tried to raise these issues on television, face bullets.

Currently, Pakistan’s largest private TV network – GEO – is under attack for allegedly airing a blasphemous morning show. The controversial content was a lapse of editorial judgment but the charges have put thousands of workers’ lives at risk. The channel that has been in a tug of war with Pakistan’s premier intelligence agency – the ISI – has now been entangled in the ultimate crisis. It may mend its relations with the state but charges of blasphemy will continue to risk its staffers.

Protecting Islam?

Pakistan has turned into a society where even an allegation of blasphemy is enough to sentence and burn people. In Sindh and Punjab mobs have burnt the accused reminding one of the ugliest of practices in human history. The abuse of blasphemy law is nothing but an issue of power and ideological supremacy by the fanatics in our society.

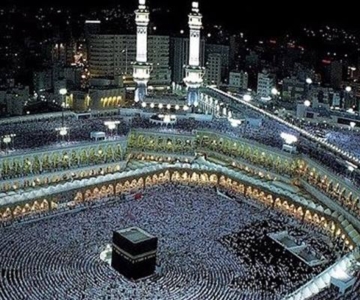

Ghazi Ilmudin Shaheed, who killed a Hindu writer for blasphemy in the early twentieth century, is a national hero of Pakistan’s collective memory. It cannot be denied that the love and veneration for Prophet Mohammad (pbuh) is a tenet of lived Islam across the Muslim world. However, in Pakistan’s case, this is less of a religious obligation and more of a political project. Implementing the blasphemy law with or without the due process is a means of dealing with a pre-Islamic past, the colonial experience, and modernity.

Above all, it is a direct result of a state project which has drummed Islamo-nationalism to build widespread public support for “strategic” aims. The battle with India is not about Kashmir or water but it is about believers vs infidels. Similarly, the engagement with the West can be managed by invoking the spectre of West attempting to harm Islam and Muslims.

This is why a good number of my countrymen view the debate on blasphemy law as “Western agenda” and something that West sponsored “evil” NGOs propagate to damage Islam and Pakistan. Are we the only Muslim country on earth? There are at least a billion Muslims living outside Pakistan and we cannot assume the gatekeeping of Ummah. No one denies that the Western aggression and misadventures haven’t helped either. But we are now trapped in our own discourse, glued to an identity that values exclusion over pluralism. The rise of such discriminatory discourses in Pakistan through publications, media, militant groups – considered legitimate – have compounded our everyday reality. Upholding human rights is now a sin punishable by death.

We do stand at an abyss whether we like it or not.

In the short term, Pakistan’s Parliament needs to change the investigative procedure of the blasphemy law and institute safeguards against adverse police reporting. Most importantly, it will need to protect the judges and lawyers who defend human rights.