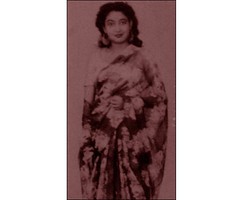

End of an era: Ainee Apa 1927 – 2007

Why do we all find ourselves present in this particular context, in this particular place? How have these pictures assembled here in this jigsaw puzzle? Soon, something will happen, pieces will scatter and become part of a newer pattern? This time will pass? (From My Temples, Too)

The death of Qurratulain Hyder marks the end of an era of the finest writing in Urdu. Hyder, also known as Ainee Apa, dominated the world of Urdu literature for over six decades. She started writing as a child and published her first novel, Meray Bhi Sanam Khanay (later trans-created as My Temples, Too), when she was 22 years old. The novel set a new trend in Urdu literature: a voice of modernity, yet one rooted in the traditions of the Indo-Muslim ethos as it struggled to narrate the tragic tale of the birth of two new nations. Even her worst critics, the doyens of the Progressive Writer’s Movement, acknowledged her innate gift for writing. Within three years, her second novel was published and she had unwittingly kick-started the revival of the Urdu novel from the point where Munshi Prem Chand had left it in the early twentieth century.

The death of Qurratulain Hyder marks the end of an era of the finest writing in Urdu. Hyder, also known as Ainee Apa, dominated the world of Urdu literature for over six decades. She started writing as a child and published her first novel, Meray Bhi Sanam Khanay (later trans-created as My Temples, Too), when she was 22 years old. The novel set a new trend in Urdu literature: a voice of modernity, yet one rooted in the traditions of the Indo-Muslim ethos as it struggled to narrate the tragic tale of the birth of two new nations. Even her worst critics, the doyens of the Progressive Writer’s Movement, acknowledged her innate gift for writing. Within three years, her second novel was published and she had unwittingly kick-started the revival of the Urdu novel from the point where Munshi Prem Chand had left it in the early twentieth century.

Her genius found a panoramic range of expression in Aag Ka Darya, which for its canvas, historical consciousness and characterisation, surpasses most novels written in any language. This novel deals with the plight of the human condition in the Indo-Pakistani setting from the fourth century BC to the 1950s. Starting with a translation of a TS Eliot poem, it traces multiple eras, with characters disappearing and reappearing in different guises, pitted against the broad strokes of history and time.

It was an epoch-making event in Urdu literature, but ran into trouble in Pakistan, as the novel highlighted the thousand year old composite Indo-Muslim culture of pre-Partition India, something which was not in line with the official version of history being constructed in Pakistan. Ideologically driven right-wing critics considered it a threat to their nationalism.

The main characters of the novel, Champa and Gautam, meet and separate through the ages. Passing the river of fire that spans centuries, they immortalise the human quest for meaning and happiness. In the process, readers get insightful glimpses at the history, culture and sociology of India from the fourth century BC to the 20th century AD.

The main characters of the novel, Champa and Gautam, meet and separate through the ages. Passing the river of fire that spans centuries, they immortalise the human quest for meaning and happiness. In the process, readers get insightful glimpses at the history, culture and sociology of India from the fourth century BC to the 20th century AD.

A disheartened Ainee returned to India around 1960 and continued her literary career, despite the fact that Urdu was a fast declining language in the country, and its main readership was in Pakistan. But what forces could daunt Ainee? Her stature and recognition by luminaries such Nehru and Azad, her fiercely independent personality and sheer creativity made her adjust well to the new post colonial India. This was despite the fact that her stories did not always flatter the Indian establishment.

Her other major novel, Aakhire Shab Ke Hamsafar, which won several literary awards in India, concerned a group of highly charged idealists who struggled during the pre-Independence era, victims of the vagaries of time. The characters become disillusioned with life and eventually compromise their principles in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh respectively. But the narrative is not about this political dimension. It is about time, its ruthlessness and the frailties of the human character‚ making it a universal novel in its tragedy and sweep. The later characters in this novel are strong and clear headed, reflecting Ainee’s innate optimism about the younger generations and her faith in the progress of South Asia.

Gardishe Rangi Chaman (Gardishe) and Chandnee Begum ostensibly concern the decline of Muslims and Muslim civilisation in contemporary India and its interface with modernity and globalisation. However, beneath these themes, alive in the sub-text, are universal themes of man’s relationship with time and space. In Gardishe, she also explores an impressive range of subcultures, dying and flourishing, such as that of Anglo-Indians, Sufi khanqahs, street performers, prostitutes and the nouveau riche classes of the post 1947 subcontinent. In these decades, she also managed to write countless short stories and novelettes, all of which are diverse in their subject matter and tone.

Gardishe Rangi Chaman (Gardishe) and Chandnee Begum ostensibly concern the decline of Muslims and Muslim civilisation in contemporary India and its interface with modernity and globalisation. However, beneath these themes, alive in the sub-text, are universal themes of man’s relationship with time and space. In Gardishe, she also explores an impressive range of subcultures, dying and flourishing, such as that of Anglo-Indians, Sufi khanqahs, street performers, prostitutes and the nouveau riche classes of the post 1947 subcontinent. In these decades, she also managed to write countless short stories and novelettes, all of which are diverse in their subject matter and tone.

Her novella Aglay Janam Mohay Bitya na Kijyo is a fine specimen of class and gender exploitation and has become an iconic literary marker within the Urdu language. Ainee’s most experimental and expansive work was an autobiographical novel, Kare Jahan Daraz Hai, which traces her genealogy from Central Asia and recounts her family and personal stories in a complex mosaic of style, technique and ever-changing ambience. As is the case of her novels, Ainee’s autobiographical novel remains the best in its genre. As CM Naim, the Chicago based professor, noted, it expands the potential of experiencing life.

Sita Haran, published in 1960, is an elegy to the sense of betrayal at a personal and political level, an experience not uncommon to humans. In it, a modern Indian woman, separated from her husband and living with her lover, struggles for the custody of her only child in a frantic attempt to remain in touch with her past. Meanwhile, Housing Society explores the lives and tribulations of three migrant families and how their world is turned upside down in post-Partition Karachi. In this novel, two affluent families of yore become homeless, while the poor country cousin, through an alliance with the new political and economic classes, becomes a powerful business magnate. The legendary character Hasan Nasir, a Communist party activist who was tortured to death in 1962, is said to be the inspiration for one of the key characters. Another gem, Pat Jhar Ki Awaaz (The Sound of Falling Leaves) has a protagonist who meets an old acquaintance in a Lahore bazaar, bringing back memories of her teenage years in Delhi, memories of sexual awakening and her interface with the middle class morality which restrained her self expression.

Sita Haran, published in 1960, is an elegy to the sense of betrayal at a personal and political level, an experience not uncommon to humans. In it, a modern Indian woman, separated from her husband and living with her lover, struggles for the custody of her only child in a frantic attempt to remain in touch with her past. Meanwhile, Housing Society explores the lives and tribulations of three migrant families and how their world is turned upside down in post-Partition Karachi. In this novel, two affluent families of yore become homeless, while the poor country cousin, through an alliance with the new political and economic classes, becomes a powerful business magnate. The legendary character Hasan Nasir, a Communist party activist who was tortured to death in 1962, is said to be the inspiration for one of the key characters. Another gem, Pat Jhar Ki Awaaz (The Sound of Falling Leaves) has a protagonist who meets an old acquaintance in a Lahore bazaar, bringing back memories of her teenage years in Delhi, memories of sexual awakening and her interface with the middle class morality which restrained her self expression.

Ainee’s personal relationships were never smooth. She never married and perhaps never had a companion in the romantic sense. There were suitors and admirers of all kinds, but there was a tragic lack of connection, perhaps intellectual and cultural more than anything else. Like Champa, her legendary character, she remained alone to the end, and the reasons for her choice are not known to any. However, this solitude enabled her to protect her individuality, creativity and sense of the self, which it can be argued, resulted in great literature.

Ainee’s personal relationships were never smooth. She never married and perhaps never had a companion in the romantic sense. There were suitors and admirers of all kinds, but there was a tragic lack of connection, perhaps intellectual and cultural more than anything else. Like Champa, her legendary character, she remained alone to the end, and the reasons for her choice are not known to any. However, this solitude enabled her to protect her individuality, creativity and sense of the self, which it can be argued, resulted in great literature.

Not content with fiction, Ainee’s creativity in later years found an outlet in rediscovering the essentials of Indo-Muslim civilisation. She dug out the first subcontinental novel, entitled Nashtar, authored by a late 18th century East India Company official, Hasan Shah. This invaluable script and its 1890 translation were lying neglected in the Patna library archives. Ainee translated and published it under the title The Nautch Girl, with overwhelming excitement that the modern novel was not the preserve of the English speaking world. This discovery is lesser-known and (like many others) underrated. There were critics and sceptics, but Ainee held her ground and had no patience for the self-flagellation which a post-colonial South Asian mind often indulges in.

This is an outstanding contribution to the corpus of South Asian and world literature. Posterity will treat it as a major landmark in the evolution of subcontinental literature. In my meeting with her, she elucidated how modern this novel is in terms of its characterisation, mood and technique. There were traces in it of what was to be known at least a century later as the stream of consciousness technique.

Another major book, which she co-authored with Malti Gilani, explores the musical legend Ustaad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, the master of Indian classical music. This is an authoritative biography which remembers not just a life, but also the intricacies of a legacy left by a musical genius. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Ainee were two luminaries whom Nehru urged to return and enrich the post-colonial Indian cultural landscape.

Ainee is perhaps the only Urdu writer to have translated her own works in English. Her trans-creations are competent but, for obvious reasons, they are not at par with the original versions. The Times literary supplement commented on the publication of River of Fire ( Aag Ka Darya ): “Now Anglophone readers can see whether the fierce beauty of her imagination transcends the limits of language and nation.” Fireflies in the Mist was published earlier, and she also translated Aglay Janam as The Street Singers of Lucknow and other stories.

Through six decades of masterful writing, she did not let the author-writer syndrome possess her. She was, to put it mildly, allergic to being treated and addressed as a writer. Ainee Apa found such a demeanour ‘cheap’ and writer pretensions phony. Apparently, she could write even when in the company of friends, and the late Dr Aftab Ahmed narrated a scene from a little gathering in the 1950s, where Ainee was seen reclining on the floor and writing her novel while friends were conversing and joking! When she was not writing, Ainee played the piano, painted or worked as a journalist (she edited the Indian magazine Imprint and remained on the editorial board of the Illustrated Weekly of India for nearly a decade).

Unfortunately, Ainee was misunderstood at various stages of her life. As a 20-something writer she was scoffed at by the hardliner progressives for being too bourgeoisie. The critics and contemporary writers in Pakistan had their share of misgivings, and the establishment considered her writings to be too much in conflict with the two nation theory. Her eccentricities were construed as feudal arrogance.

Abdullah Hussain plagiarised sections from Aag Ka Darya in his novel, Udas Naslain, considered to be another major Urdu novel, and later termed it as a tribute to the great writer! Qudratullah Shahab, the bureaucrat writer turned self-declared sage in his later years, misrepresented her in his magnum opus Shahabnama. Worst of all, she lost all the royalties from her best-selling books. She had, at an international literary event, claimed a Guinness world record for not being paid anything for the thousands of books which were pirated in Pakistan. This is why she was wary of Pakistan, though it remained her second home until her last breath.

I am fortunate to have met Ainee Apa twice. Even though I met her in the twilight of her fascinating life, she had not lost her brilliance as a conversationalist. Her wit and ability to hold forth on any subject under the sun were remarkable. We listened to music that I had collected, talked of books, Lucknow, Lahore as well as her spiritual moorings. I wish I could meet her again. Her death was not a run of the mill death of an old writer, but the death of a grand vision of a civilisation, and at an individual level, a part of one’s self as a reader. She had the ability to take the reader into the labyrinths of cultural consciousness and will surely continue to inspire generations of readers and writers.

Javed Akhtar, the Indian lyricist, said after her death that he felt sorry for, ‘those people who read fiction but have not read Hyder”, and that a time will come when her works “will reach everywhere.” Her stature in world literature will find its place. Although she has been compared to Marquez and Kundera, her range and depth in portraying societies, cultures and individuals remains unmatched.

Javed Akhtar, the Indian lyricist, said after her death that he felt sorry for, ‘those people who read fiction but have not read Hyder”, and that a time will come when her works “will reach everywhere.” Her stature in world literature will find its place. Although she has been compared to Marquez and Kundera, her range and depth in portraying societies, cultures and individuals remains unmatched.

Ainee Apa shall live on in her stories.

Ainee Apa’s Works Cited – click here

Awards and Honours – click here

An earlier version of this piece was published by the Friday Times, Pakistan