Rehana Hyder writing for the Friday Times

My first recollection of Annemarie Schimmel was as a teenager in Delhi in 1969, in the year of the Ghalib Centenary celebrations, when my mother sent me to her hotel room with a single long-stemmed rose and a note with ‘ sher o shairi, ‘ the usual mode of communication between the two literary ladies. I remember her as striking and sparkling, tall and blonde, always wearing something reminiscent of strawberries, sunshine and cream. She had probably even seen me as a toddler during my parents’ previous posting in India. The only person I know who has known her longer is my old friend Anadil Rashidi, whom Annemarie Schimmel blessed like the proverbial Fairy Godmother at her birth in the sacred, Sufi land of Sindh, her favourite part of Pakistan.

Thereafter, Annemarie Apa was woven into the fabric of my life, and intricately so when we lived in her country of origin, Germany, in the early 1970s. I learnt with wonder how, in Saxony as a girl, she had written and painted the Orient, East and South Asia in particular, under the encouraging eyes of her enlightened ‘eltern.’ Her Mother, whom we all came to call ‘Mama,’ and she resided in an old, spacious, light-filled apartment, Lennestrasse 42, overlooking a tree-lined avenue near the University in Bonn.

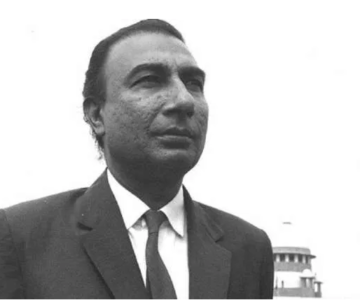

We were frequent guests to high tea, a feast for the eyes, taste and mind. Mama saw the world through her brilliant daughter and gave Annemarie invaluable editorial assistance as well. Likewise, there was no occasion Annemarie would willingly miss at Pakistan House, despite her trans-world lectures and professorships both in Bonn and Boston (Harvard). She had a wonderful rapport with my father as well as my mother, and they would always greet each other enthusiastically. Her presence and her friendship, shared with Foreign Office and academic friends such as the Berendoncks, the Kurt Mullers, Hauthals, Heimsoeths, Lothar Lahns, Brunhilde Dorr, the Saeed Ahmads and the Laiq Alis, was a major reward in my father’s challenging tenure as Pakistan’s ambassador to West Germany. Similarly, on his revisiting Bonn in the early ’80s to lecture at the Foreign Office Institute, her comradeship and collaboration was a highlight.

When we left for Moscow in 1975, the rapport continued – we must have an album full of Oriental miniature postcards with her distinctive handwriting on the back, plus autographed copies of her masterpieces, including her commentaries on calligraphy. She would, from her frenetically hectic schedule, find the time to write, and never forgot to ask how Saad’s exams were or Rani’s Oxford activities or Tariq’s postings. Once in the late ’70s, at Harvard, when she took my brother Tariq, who was then on a fellowship at the Law School, to dinner she told him the fascinating story of how the university’s Oriental chair had been endowed by the ‘founder’ of Uncle Ben’s Rice, an Afghan émigré to America in the early 1900s, who developed the patent for parboiling rice, and willed much of his consequent fortune to Harvard for setting up the chair. A fact known to few.

Apart from all her astonishing attributes she was blessed with a wonderful sense of humour, not always a quality found in one so academically endowed. “I read in my horoscope today,” she once remarked to my father, “that something extraordinary would soon happen to me – I guess either I shall get married or I shall soon die!” Fortunately the latter proved not to be the case. As for the former, she once replied to a typically Pakistani question, “I never thought of it!”

Spoilt with all this background and intimate interaction with the great lady, I was additionally blessed with a cameo experience of Annemarie Apa at university. During a visit of hers to London, and though she was no stranger to Oxford or any of its specialised academies viz. Professor Hourani’s Oriental Institute, she agreed for my sake to come to my college, St Hilda’s, and address a gathering on Sufism. For three days I whirled around arranging the event in a dervish-like frenzy whilst she spent her valuable time dignifying my little room in Garden Building. The look she gave me as she spoke, in the Edwardian elegance of the Lady Brodie Room, its French windows open onto the gardens and the river, made it all worthwhile. I doubt that the room had ever hosted a larger or more mesmerised audience, which included Benazir, whom she now knew well from Harvard, or that anyone has ever ‘travelled’ thus, magic carpet and Alif-Laila like, to the ‘Mystical Dimensions of Islam.’ For whenever she spoke in public she would close her eyes relying on her photographic memory, and be off, and her listeners with her, as if she was indeed seeing all nature though Maulana Rum’s ‘fragrant veil of green’ and all humanity through the Kafis and Kalaam of Bulleh Shah, Waris Shah and Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai.

This is how I recall Annemarie Schimmel in the 25 years following my parents’ retirement to Islamabad in 1981, either addressing large audiences through the excellent acoustics of the German Embassy auditorium, or chatting informally at the German Residence or our home.

When Prof Schimmel was awarded her much-deserved German equivalent of the Nobel Price for literature and interdenominational understanding – for which she travailled tirelessly – she had to confront the vested and vitriolic attacks of the now prevalent anti-Muslim brigade. When she was asked how she would desire her attackers to be dealt with, she smiled serenely and said, “I hope that they never have to suffer the agony that they inflicted upon me.” This was related recently by Ambassador Shafqat Kakakhel, himself an Arabist, who likewise knew her personally in Bonn.

A few days after my father’s demise in October 2000 I was fortunate enough to chance upon her, like the proverbial Angel of Mercy, during a whirlwind trip to Islamabad. “Dear Rani,” she said after asking about my mother, “just before I boarded my flight in Frankfurt I asked the Consul General to give me news of Sajjad Hyder Sahib. He’s just passed away, he replied.” “Annemarie Apa, do you think he’ll be all right up there?” I tremulously yet hopefully asked, holding onto her. She raised her hands most naturally in prayer, looked up, and smilingly said, “Of course”! She may or may not have been a Muslim; she was most definitely a Sufi.

Rehana Hyder lives in Islamabad