Shaan Taseer’s debut solo exhibition is a ceremonial homecoming for the artist.

It has taken the gifted Shaan Taseer almost two decades to focus on the natural habitat of his soul, art. This has finally happened. Earlier, this month, 35 artworks by Shaan, all watercolours, were exhibited at the Chawkandi Art Gallery in Karachi and the show was quite a success. All the paintings were sold, but more importantly this was the moment of arrival for an artist who has resisted the path for some time.

I have known the artist for many years and had seen some of his sketches and watercolours long before. Shaan’s innate talent was chiselled at school and such was his dexterity with lines that I even suggested he pursue his passion as a career. In those days, all of us were busy studying what was relevant, and the choice of plunging into the world of the starving artist archetype was a risk that Shaan did not take. But he continued sketching. While living abroad, he absorbed inspiration from myriad sources. The way North African cities were built and the way the migration of humans and ideas was part of the limitless globe all seem to have influenced the evolution of his style.

Still, regular sketching and painting did not prompt him to pursue it seriously. He remained busy in the world of finance and management, pursuing what we all have to: a plain, decent livelihood. Shaan lived in different cities, underwent many experiences pleasant and unpleasant, raw and gentle, and perhaps the artist in him kept bottling it all up for later expression.

Life took some dramatic turns and perhaps two are noteworthy here. First, after his education abroad, Shaan returned to Pakistan, worked with his late father’s business empire, left it, and found his own career path, discovering a life that lay outside the confines of familiar security and luxury. Second, the brutal murder of his father, Governor Salmaan Taseer, in 2011 obviously left a deep impact on his psyche. More so, the barbarity, the helplessness of Pakistan’s thinking sections, and the growing power of extremists.

A few months after this ghastly incident and the kidnapping of his half-brother Shahbaz Taseer, Shaan found himself thrown into the cauldron of contemporary Pakistan. The events both personal and political were traumatic and would have undone an ordinary mortal, but Shaan dealt with them in his signature happy-go-lucky style. The purpose of narrating his personal story is to show that Shaan’s artworks on display are both a reaction to his recent personal history as well as an emotional outburst through colours.

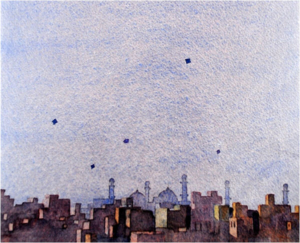

The ensemble of tender watercolours on display speaks of an aesthete who is not a studio creature, but engages with society and is willing to deal with it. The exhibition, titled Cities, plays on many themes, notably, the idyll of urban space where a linear architectural view is disrupted by symbols: flowers, balloons, graffiti, kites, and other representations.

Most of the artworks employ varying shades of white space and highlight the organization of a city through rows of houses that could be anywhere, not just Pakistan or places Shaan might have lived in or visited. There is an elusive symmetry as well that hints at a Mediterranean feel, but the ambience is subverted by distinct features that speak of contemporary Pakistan.

So, in a work that showcases a silent city with no human figures, a line from Pakistan’s pop art Dekh, magar pyaar se (Look at me, but with love) changes the vision. There is a plane hovering over the city, trailing behind it the same message. The plane, when I first saw it, resembled a drone, but its position in the frame changes the meaning of all the city represents.

Of late, Shaan the artist has also been prominent as a political activist. Using social media and public protests as a tool, he has been advocating resistance against the various shades of extremism. Therefore, a recent work titled Lal Masjid uses the white dome as indicative of the place of worship, but with red flowers concentrated around it. Deep red, a shade of bloody crimson, these symbolic instruments remind one of the blood that has flowed across Pakistan in recent years. The dome, as the imagined state of humans, is encircled by forces of Nature that weave a story. In part, this idea is inspired by the movement to reclaim Lal Mosque, a symbol of Pakistan’s capitulation to religious extremism, but this a larger narrative that covers the entire country.

Behind the dome are gravestones to signify that any pretences to kindness and compassion that religion assumes died with Lal Masjid. Regardless of the political idea whether reclaiming one seminary amid a sea of state-sponsored seminaries that radicalize people into taking others lives and offering up their own this is a powerful composition.

The colour red, therefore, in many other paintings comes as a departure from the serenity of white, pale blue, and other hues of sky and the city. It intrudes as a powerful reminder, a story-setting context. In my favourite work, titled Shikarpur, which commemorates the attack on an imambargah, red balloons overtake the painting. There is both mourning and a form of suspension inherent in the use of the symbol.

For the artist, cities act as organisms in themselves with a memory and a culture

Why are there no human figures in this series? Cities here act as organisms in themselves with a memory and a culture; humans, according to the artist, are represented by the architectural representations. Homes, domes, the urban layout often in idyllic constancy also tell a story of the lost character of cities we have lived with. In Maghrib ki Azaan, the kites in the sky against the backdrop of the majestic Badshahi Mosque also hint at the cultural erasure Lahore has gone through, in particular since Basant was banned through legal and political instruments ostensibly to save human lives from the lethal string some kite-flyers use, but in reality, to reshape the city in a different mould, under a view that caters to the supremacy of mullahs (who find such festivals un-Islamic) and to the rampant destruction of trees and heritage that has taken place in the wake of modernization.

This is why, in another work that resembles Morocco, the Coca Cola advertising logo rudely interrupts the painting and speaks of the corporatization of the idea of the city and, by extension, of life.

These reflective works denote a struggle, the grappling with everyday urban reality in Pakistan and elsewhere. Violence, subverted reason, and the fading of a city’s memory emerge in the melancholic milieus depicted. Quite naturally, the use of red, which signifies human existence and life forms, enlivens these cityscapes.

Prior to this exhibition, Shaan had been showcasing his works online, including a series of striking portraits. One caught the attention of many a puritan: a portrait of Mr Jinnah, inspired by a real photograph in which he was smiling. Shaan interpreted the photo and brought out the everydayness of the human being that Mr Jinnah was. There was endless controversy and a good dose of invective hurled at the artist. But this was some time ago and outside the precincts of the art establishment. The series Cities is a ceremonial homecoming.

By weaving the personal with the political, Shaan Taseer has augmented the conversations of our times

I celebrate Shaan’s formal entry into the world of Pakistani art. The diversity of contemporary art in the country stands enriched. It is too early to judge the place of these works in ongoing artistic movements, but by weaving the personal with the consciousness of the political, Shaan Taseer has augmented the conversations of our times.