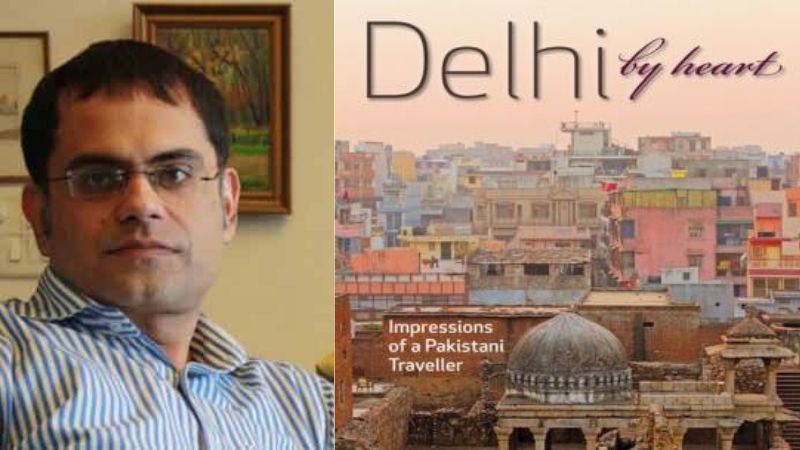

Here’s an excerpt from my book ‘Delhi, by heart’ that was featured in TFT

I am not sure how I met Bunty. It was perhaps through a reference from the office during one of my early work-related visits. Bunty Singh, brother of Sunny Singh and Goldie Singh, became my guide and companion. Sunny and Bunty have set up a mini empire of rental cars through investments made by Goldie who lives in Germany and is married to a “good” German girl. Bunty, a boisterous, internet-savvy young Sardar, found me to be somewhat like him. We spoke in Punjabi, often using lines that would quite miss those outside the ‘Punju’ realm. And we both were equally fascinated by each other-the thirty-something grandchildren of Partition.

So after an hour of awkward client-service interaction, Bunty decided to befriend me. It was just the right thing to have happened I guess. How else would I know a real Sardar? Most of my interactions with Sikhs took place when I was a student in the UK decades ago.

However, as soon as there was mention of Partition, there was a palpable unease. It was only after a day or two that he confided how half his family was butchered at a railway station.

To use Amrita Pritam’s words:

Who can guess

How difficult it is

To nurse barbarity in one’s belly

To consume the body and burn the bones?

I am the fruit of that season

When the berries of Independence came into blossom. (Translated from the Punjabi by Harbans Singh)

Quintessential to the Delhi experience, this site mixes time and memory. From 1450 BCE to the present day, the monument tells various stories. The standing walls that we see today are most likely the work of the unfortunate Emperor Humayun, who chose this as a residence in Delhi and added many structures to the ruins. Proximity to the Jamuna must have played a part-in hot Hindustan, water and breeze were essential for survival.

In 1555, Humayun regained control of Delhi and he returned to his Din Panah. In a year’s time, he tumbled down the stairs of Sher Mandal with books in his hand, thereby ending his tumbling life. Not far away from this place lies his magnificent tomb, reflecting the grandeur of Gur-e-Amir of Tamarlane in Samarkand. He was succeeded by the greatest of emperors, Akbar. Little did Humayun know that three centuries later, his descendent, Bahadur Shah Zafar, would escape from the Red Fort to take a boat down the Jamuna and reach Purana Qila to go to Hazrat Nizamuddin’s shrine. Also, Humayun would have never imagined as he was dying that the last Mughal emperor would be captured by the British at his tomb.

Bunty tells me in chaste Punjabi, “Aais jaga tay badi history haygee!” (‘Too much history in this place!’) We walk around a huge well and cross the royal baths until we find a little tea-stall. Bunty is amused with my ramblings. He is also interested in the Sikh shrines in Pakistan. These are well looked-after, I reassure him, and inquire why his family has not yet visited Pakistan.The Mahabharata tells us that Delhi was founded on a jungle inhabited by ancient tribes. The Pandava brothers cleared the jungle and eliminated all its inhabitants to build Indraprastha. Thus, primordial Delhi set the pattern for violence-it has always marked the city’s existence. Small wonder that all the Delhis that were to follow faced political upheaval involving a fair amount of violence. The first recorded war for the throne of Delhi- mythological as it might be-is narrated in the Mahabharata.

The events of 1947 added another life to this monument. Purana Qila was used as a vast refugee camp. Violence on the streets of Delhi had forced thousands of Muslim families to leave their homes and prepare for a long journey to Pakistan. The conditions of this refugee camp, where up to 100,000 people may have taken shelter, were appalling. Dr Zakir Hussain, later the president of India, bemoaned that those who had escaped sudden death came here to be “buried in a living grave.”

I am completely confused… shall I appreciate the beauty of the ruins or the syncretic architecture of Sher Shah or its prehistoric significance? Or shall I search for traces of the blood of those who must have died here? Accidents of history can be deaf and dumb. Like Ajeet Caur’s interpretation of the elements, history is alive yet indifferent to individual tales and personal suffering. I still have to probe these difficult questions.

In September 1947, Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Delhi to take stock of the violence and ease communal tensions. A shaken, non-violent Gandhi visited Purana Qila to witness the conditions of dispossessed Muslim exiles-refugees in their own city. I can hear him making his appeal to Hindus by comparing the predicament of the Muslims to that of the five Pandava brothers who were exiles in their own kingdom for twelve years: “It is said that in the Mahabharata period the Pandavas used to stay in this Purana Qila.” Thus Muslims “are under your protection and under my protection.” Gandhi’s tireless efforts in Delhi that included visits to the Jama Masjid, Old Delhi, as well as his rounds of fasting, brought a tenuous peace back to the city. But what a price he paid for attempting to clear the poison in the air!

Gandhi, in that season of Independence, stayed in Delhi and went from neighbourhood to neighbourhood to arrest the violence and bring about a truce between India and Pakistan and between Hindus and Muslims. Within months of his effective campaigning and fasting for these causes, he was assassinated. The greatest icon of modern Indian consciousness was an irritant in the dark world of Hindu fundamentalists. From 1934 to 1948, six attempts were made to kill him. The last one, by Nathuram Godse, was successful.Delhi must have witnessed one of its coldest days on 30 January 1948. The country must have needed Gandhi’s sacrifice to nurture its complex society and the new state. Over time, this gruesome murder of India’s greatest leader has slipped into relative oblivion. The grievances of the assassins were that Gandhi supported the creation of Pakistan, he was fasting for the payment of dues worth Rs 55 crore to Pakistan and his “appeasement” of Muslims was making Muslims more belligerent. Appeasement has become the bane of Indian politics. The major policy plank of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been to end this policy of appeasement (of minorities) and Gujarat’s Chief Minister Narendra Modi implemented a harrowing version of this political aim.

The same day we visit Gandhi’s cenotaphs at Raj Ghat. We park the car under the keekar trees and walk. The monsoon breeze has cooled the air. There are a few flower-sellers with heaps of marigolds. Bunty and I walk to the shrine and, passing through well-kept lawns, we reach the unostentatious marble platform. Not many visitors are around. This is a peaceful afternoon. As we return, I see an exquisite structure at some distance and find out that it is Zeenatul Masjid, the beauty of the mosques, built by Emperor Aurangzeb’s daughter.

A Mughal mosque overlooks Gandhi’s cenotaphs and the silent Jamuna flows, or rather trickles through most of the year, at a close distance. It is a shrunken river that has been filled with the blood and corpses of past sufferers but now it is choking with sewage and pollution. From Indraprastha to the Sultanate and the Mughal takht of Dilli, the Jamuna has witnessed centuries of violence and has changed its course several times but has been faithful to Delhi.

I hold a mustard flower in my hand and put it inside the copy of Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi that I have with me. In Delhi, time and again, I think of Ahmed Ali who could never return to the city he loved…

Raza Rumi’s ‘Delhi by Heart’ is published by Harper Collins