September, 2017: The state may be hedging that mainstreaming JuD will wean its cadres away from militancy (The Print)

In the fourth of a four-part series on on Hafiz Saeed’s new political party, Raza Ahmad Rumi writes that JuD’s decision to form a political party is intriguing as its literature and rhetoric in the past has rejected Western democracy. Read the first, second and third parts.

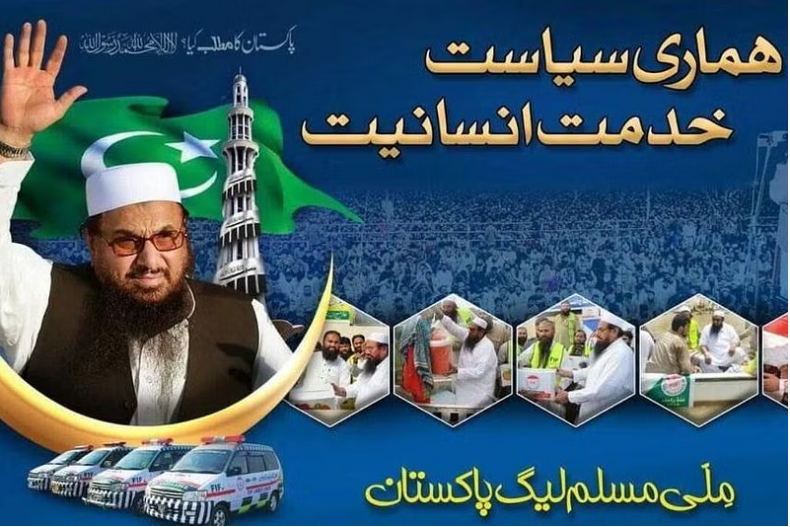

The idea that a religious political party can grab power through electoral democracy and, in turn, and take control of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is not a new one. This argument was revived in Indian media outlets, following the announcement by Jamaat-ud-Dawah (JUD), a charity organization linked with proscribed Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) to form a new political party termed Milli Muslim League. LeT was a key militant group engaged in fight for liberating Kashmir through military means during the 1990s. LeT has been accused of planning and executing attacks in Indian financial capital of Mumbai in November 2008.

In recent years, JuD emerged on Pakistan’s political spectrum with its large charity network and exhortations to influence country’s foreign policy. JuD is a brand by itself now with a grassroots network. During natural disasters and other calamities it has sprung into action and often surprised Pakistan’s civil society that has been accusing the state of letting the network grow and gain legitimacy among the people. JuD has also been holding large rallies rallies criticizing India and the United States. As a curious pressure group, JuD has called on government of Pakistan to review relations –advising an all-out severance – with New Delhi and Washington. Islamabad, however, has not taken such advice too seriously. On the contrary, Islamabad and Washington have been cooperating to boost the security of Pakistan’s nuclear complex.

Announcing the launch of a new political party, the MML representatives informed Pakistani media that the party will strive to make Pakistan an “Islamic welfare state”. MML is not the first party to espouse Islamist cause. Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) is the most prominent religio-political party active in domestic politics for past six decades. JI has stood for ‘Sharia-rule’ for decades. At the same time it hasn’t rejected democracy and has continuously participated in most elections. It could never gain a majority or even a sizeable number of seats in the national assembly. But as an ally of other mainstream parties JI has enjoyed power in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in the recent years.

JuD’s decision to form MML is intriguing as its literature and rhetoric in the past has rejected Western democracy. With its chequered past linked with JUD and LeT, MML would need to win at least a hundred plus seats to be in a position to form a government. Pakistan’s national assembly requires that the winning party holds 172 seats to demonstrate majority in a house of 342.

It is easy for MML to claim that it will play a role in national politics. But the reality is that most politics is local. Not unlike India, Pakistan’s electoral map requires support of ethnic, clan-based and tribal associations to make headway in local constituencies.

National ideology plays a little role and even Islamist calls are insufficient to mobilise the local voter seeking patronage. For MML to succeed, it would have to break local alliances forged by mainstream parties such as Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf and Bilawal Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party. And it is not easy to win national elections given the complexity of local politics. For instance Imran Khan has been striving to win an election for the past 20 years and it has yet to demonstrate that it can secure at least 100 seats from Punjab, the most populous province.

The fears of a nuclear war being launched after MML forms a government are highly exaggerated. JuD’s metamorphosis requires contextualization. Pakistan has been under international pressure to take judicial action against JuD and its leadership. Hafiz Saeed, head of JuD is under house arrest for past several months. Given the pressure being exerted, it has become untenable for JuD to continue functioning as a charity alone. By entering into political mainstream under a new avatar, it hopes to formalize and legitimize its role.

Undoubtedly, Pakistani state is not averse to the idea. Many retired military personnel have been arguing on TV that JuD cadres need to be mainstreamed. Some observers believe that this might be a tacit admission of JuD’s relative autonomy. And the state may be hedging that participation in mainstream politics will wean JuD cadres away from militant activities. And those who do not comply can be proceeded against to ‘solve’ the problem.

It would have been better if the Pakistani government were to think of a comprehensive DDR (Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration) strategy instead of piecemeal efforts such as this one. There is a wide consensus in political elites and civil society that militias are a liability. Whether that translates into action and influences policy is a million dollar question.