It is now a given that the Pakistani state is a playground for Islamism and extremism under various guises and forms. Since the passage of the Objectives Resolution in 1949, the state by design and sometimes by default has surrendered to the phantoms of the orthodox Islamic interpretation of the world. It is true that religion was central to the sloganeering for Pakistan, but the post-1947 architecture of the Pakistani state was meant to be secular and democratic. Whatever the proponents and apologists of a jihadi state might have to say, Jinnah’s words and deeds were clear. Iqbal’s vision, inspired by Islamic philosophy and strands of mystical thought, was also clearly anti-Mullah.

This was hardly surprising, as a majority of Indian Muslims, not unlike South Asians of today, were averse to orthodoxy. From the Bhakti movement to folk and Sufi traditions, mullahs and pundits have not enjoyed popular legitimacy, as their alliance with power was resented and rejected by the populace. It is also well known that Mr Maududi and his ilk were bitterly opposed to Pakistan and accused the Muslim League leadership of being un-Islamic. Even stranger is the fact that this essential truth is rarely discussed in the public domain, and excessive coverage and importance given to the orthodox champions of Pakistani nationalism in the media and in textbooks, betrays how the age-old nexus between Pakistani monarchs and the Mullahs has survived the test of time.

Ajoka theatre based in Lahore has been attempting to challenge the status quo. Its plays rooted in the folk and street traditions of the subcontinent have raised political themes and placed political mobilisation at the centre of any discussion for social change. Recently, its play Dara Shikoh was staged in Lahore, and this marked a watershed in our cultural and political landscape. Dara Shikoh, the elder son of Emperor Shahjehan, despite his brutal murder at the hands of his Mullahesque brother Aurangzeb, continues to represent a fault line that runs through the past and the present of South Asia, especially in Pakistan.

To present a play on a prince who argued with reason and reference that there was little difference between the Upanishads and the tenets of mystical Islam is no ordinary feat. After all, this is a country where powerful forces within the state and society are hell bent on turning the Land of the Pure into a haven for cultural fascism

To present a play on a prince who argued – with reason and reference – that there was little difference between the Upanishads and the tenets of mystical Islam, is not an ordinary feat in a country where powerful forces within the state and society are hell-bent on turning the Land of the Pure into a haven for cultural fascism. Above all, Dara’s stiff resistance to a militant version of Islam and its exclusionary theological constructs is perhaps most relevant in these times.

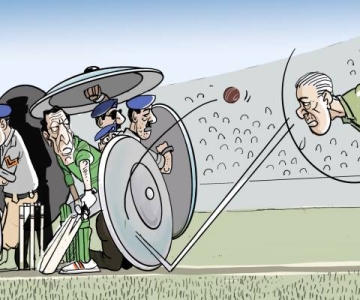

However, Ajoka’s effort to take the play to our culturally desertified and politically bankrupt Islamabad, for a presentation at the Pakistan National Council of the Arts (PNCA), has been thwarted by officialdom, as it challenges the state complexion and orientation. One wishes that such a comment were merely speculation, but it seems that there is enough evidence to suggest that a female MNA from the Jamaat-e-Islami wrote to the PNCA earlier. Apparently, she believed that Ajoka was guilty of making fun of Islamic values and represented a threat to the republic of the believers and munafaqeen alike.

How ironic that this is no different from the late 1970s when a senior bureaucrat, now a media personality and scholar (of sorts), authored an article where General Zia ul Haq was compared to the austere and God-fearing Aurangzeb, and Dara was portrayed as a precursor to Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. The maverick civil servant argued that in the clash of ideology, Zia’s coup was symbolic of religious power. Pakistan suffered from Zia’s assumed divine right to rule in the name of Islam for eleven long years, during which intolerance, bigotry, sectarianism and dictatorship shook the foundations of this country. Intellectual voices and activist groups such as Ajoka have to constantly contend with Zia’s legacy, and the wily servants of the state are always eager to provide legitimacy to retrogression.

Ajoka’s earlier play Burqvaganza explored another explosive subject, that of purdah, and its literal interpretation at the expense of the metaphorical and spiritual meaning. The female MNA referred to above, who also happens to be the daughter of the former Amir of the Jamaat, even raised the issue in the National Assembly and protested that Ajoka’s legitimate questions about the burqa were tantamount to demeaning Islam. History and politics move in cycles, and this outcry in the Parliament was not different from the earlier assaults on the secular vision of Pakistan. All our rulers, except perhaps Ayub Khan, pandered to the orthodox lobby. Under General Zia ul Haq, Islamisation became an official policy and its instruments the un-uniformed part of the national security apparatus.

A small theatre group therefore is pitted against far larger forces of orthodoxy and regressive medievalism. This is shameful, given that an elected government is ruling Pakistan, and the ruling party has been hostile to the ideology of Zia ul Haq. But Zia seems to be alive as much as his nemesis Bhutto. Whilst the jiyalas may chant zinda hai Bhutto, the institutions are pretty smug and happy to articulate zinda hai Zia. Small wonder that JI, whose lack of electoral worth has time and again been exposed, has the audacity to become a guardian of our faith and nationalism.

When Ajoka’s executive director Madeeha Gauhar called the other day to share the recent phase of her struggle in the democratic era, she was obviously disturbed. And given her penchant for speaking the truth she was also not too charitable about the Mullah brigade. While she was talking on the phone, her voice faded and a recording of a Hamd (a eulogy for the Almighty) emerged from nowhere. This was amusing, yet quite unnerving. Our Constitution and laws prohibit anyone to monitor citizens expression and speech in the public and private spheres. And, to experience this intrusion was not pleasant at all.

Interestingly, the minions of Big Brother played a popular Hamd, that begins with the verse Koi tau haye jo nizam-e-hasti challa raha haye. Muzaffar Warsi, who apparently was Zia ul Haq’s favourite poet, had composed these verses. In view of his special place in the Zia kingdom, he was accorded with various state honours and also a cushy state job. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan later rendered this piece in his magical voice.

I clearly remember a discussion that took place in the presence of the late Ahmed Nadeem Qasimi, a twentieth century literary giant. Many senior poets critiqued this Hamd for being a problematic hymn for God Almighty, since it did not express absolute belief in God but worked through an inference: there must be Someone who was managing the universe! Thus the element of doubt marred a believer’s chant in praise of his Creator.

More importantly, the bugged phone line sent a clear message: that la-deen (irreligious as secularism is understood by the clerics) Madeeha Gauhar had to be censored even in a private conversation, and reminded that there is a God. And, the chosen, self-appointed representatives were managing the show in His name.

This is not limited to the minions of the state apparatus. Such attitudes are now embedded in our curricula, modes of instruction, thousands of madrassas and more dangerously, elements of the media who were trying to convince us of the glories of the Taliban until the Pakistan Army valiantly took on the miscreants.

The Ahmedis are hounded on a regular basis, the Shias are being murdered and even the Barelvi majority feels unsafe given the high profile murders of their leadership

A journey that commenced with the Right’s struggle to capture political space in the 1940s, and with the state’s cynical support, has culminated in capitulation to such forces. The gradual erosion of Jinnah Pakistan has also led to the ascendancy of all that Pakistan was not supposed to represent. The Ahmedis are hounded on a regular basis, the Shias are being murdered, and even the Barelvi majority feels unsafe given the high-profile murders of their leadership. What we have is a curious mix of a Wahabi-Salafi variant of Islamism with several local offshoots, which are not averse to using violence and butchery as weapons.

The propagation of Islam in the subcontinent was the handiwork of the Sufis who showed the path to a large number of people through the message of tolerance, harmony and reconciliation. Recognising the roots of our indigenous cultures is now the only weapon that Pakistan’s intelligentsia possesses

The propagation of Islam in the subcontinent was the handiwork of Sufis and sages who showed the path to a large number of people through the message of tolerance, harmony and reconciliation. Violence simply did not deliver in this part of the Islamic world.

This is why recognising the roots of our indigenous cultures is important. It is now the only weapon that Pakistan’s intelligentsia possesses. To encourage the airing of alternative messages and interpretations such as Dara’s worldview, and challenging the burqa’s form over the spirit are crucial to sustain our plural culture. If Zaid Hamid can have access to state institutions such as the Iqbal Academy in Lahore, then why is Ajoka denied a space? Is it not a brazen indicator of Zia’s legacy hounding our generations well into the future? Pakistani youth are already despondent, as all the surveys reveal, about the country’s future. They have to be educated about our history and the ways in which we can co-exist as a heterogeneous country.

Education reform and mass-awareness campaigns are also needed to challenge Zia’s Pakistan. The systemic collapse in the education sector will need to be arrested immediately if we have to survive as a viable polity. A plural culture also needs secular education and an inclusive political system that provides avenues for all voices and opinions. It is about time we became unapologetic in dealing with the narrow-mindedness of the Mullah and reclaimed Iqbal’s message, that called for ijtihad in line with the changed times.

In this twenty-first century onslaught of medievalism, Pakistanis will have to bitterly oppose any form of violence from censorship to target killings and exclusion. The religious parties who opposed Pakistan cannot be allowed to continue blackmailing us in the name of a universal, peaceful religion based on equality and tolerance. The state has to reinvent itself, and only Pakistan citizens, its intelligentsia and secular political parties, can help achieve this. The other option is too violent to imagine.

Published in TFT this week

Raza Rumi is a writer and policy expert based in Lahore. He blogs at http://razarumi.com; and manages Pak Tea House and Lahore Nama e-zines. Email: razarumi@gmail.com