Nicholas Cranfield considers work that draws deeply on traditional Islamic art

FATIMA ZAHRA HASSAN has been teaching in London for more than a decade, and is an accomplished artist. Dr Hassan’s little show of some 17 works happily fits the commercial gallery in St John’s, Notting Hill, in London, where the blank white walls draw the eye by their rich palette.

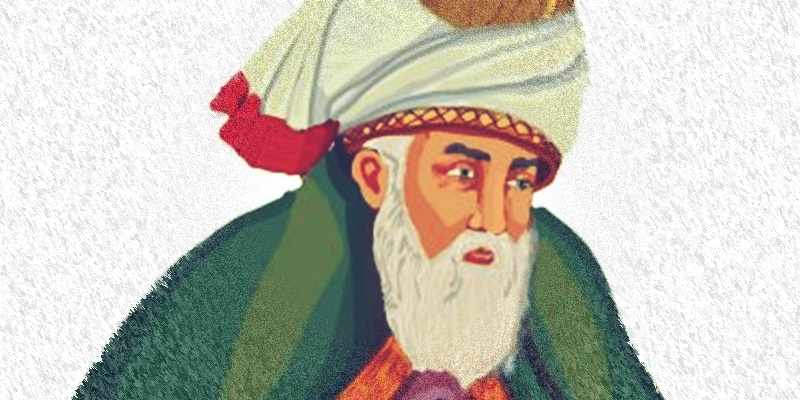

Three are illustrations for the Kingdom of Joy by Jalal ud-Den Rumi; the rest are infused with a sense of the Divine Love, Universal Brotherhood, and Peace that so characterises the Sufi tradition. The largest frame holds a portrayal (32.5 x 41.5cm) of the aged Rumi (d.1273), sitting with his beads and looking out over his long beard. Behind him is a background of petals that seem to suggest a transcendence of their own. The simplicity of form and of shape in many of these small paintings, almost all of which use gouache on wasli paper, profoundly mirrors traditional Muslim art.

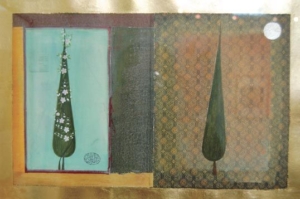

The Union is a delightful double-page picture of two poplar-like trees, one green and the other ringed with blossoming flowers, whose outlines echo one another as if yearning to cross the page to fuller union. In Two Kindred Spirits, swirling dervish figures, their hands lost in their capacious sleeves, are mirror echo to one another. Both could be pages from an ancient Islamic chronicle or storybook. But Hassan also allows herself to subvert the very culture that informs so much of her work. The 2000 piece A Man of Surfaces depicts a noble man, smoking his narghile and holding a carnation in a customary pose. With a telling insouciance, however, he has crossed one leg across the other, and reveals the left sole of his foot to us. Is this religious and social faux pas an inside joke or an attempt to invert tradition? Her earlier work (1994/95) Fihi Mafihiz looks at first like a Mughal narrative painting with all its storybook precision. Looked at in detail, we find that miniature photographic heads of her friends Kahlid, Paul, Keith, Ricky, and even the young artist herself have been pasted on to the figures. In several other works Hassan seems to be playing with ideas of post-modernism and deconstruction: figures are rendered in such a way as to disappear into the very texts drawn in behind them. All light, but perhaps not shedding much Light