Since 1977, military or quasi-military governments have ruled Pakistan. The basic tenet of such a governance structure has been centralization and denial of multiple identities that Pakistanis have. Recent reform via the 18th Amendment has opened up a debate on new provinces. Not long ago, division of provinces was a taboo. Not anymore. This by itself is a major victory of the quasi-democratic process since 2008, howsoever flawed and contradictory it might be.

Remember this is a country where the largest federating unit – East Pakistan (Bengal) was denied its due in power and resources leading to the tragic events of 1971. From 1955-1970, ethnic, linguistic and local identities were forcibly negated under the One Unit. After the creation of Bangladesh, the federal debate focused on Punjab versus the rest of Pakistan. Even the elected Prime Minsiter, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto ordered Army operations in Balochsitan and the North West Frontier Province to quell insurgencies and demands for local autonomy. Zia’s rule (1977-88) was a major setback to the federal project as Sindh was at the receiving end and the smaller provinces were remote-controlled from Islamabad. During the decade of democracy (1988-1999), things improved but only marginally.

Musharraf’s rule witnessed the brazen undermining of provincial identities and powers through a centrally imposed local government system and army action in Balochistan, FATA and parts of Khyber-PakhtunKhwa (KPK). The brutal murders of Akbar Bugti and Benazir Bhutto were viewed as another attempt by the ‘Punjab-dominated’ Army to eliminate leaders from smaller provinces. Since Musharraf’s departure and return of an elected Parliament, major structural reforms have been introduced in the form of a revised formula for national revenue-sharing, the clauses on provincial autonomy and abolition of 17 federal ministries. The transition is slow as the implementing national and provincial bureaucracies are change-averse; and the ‘systems’ – the institutions, norms and formal rules – are yet to adapt to new realities.

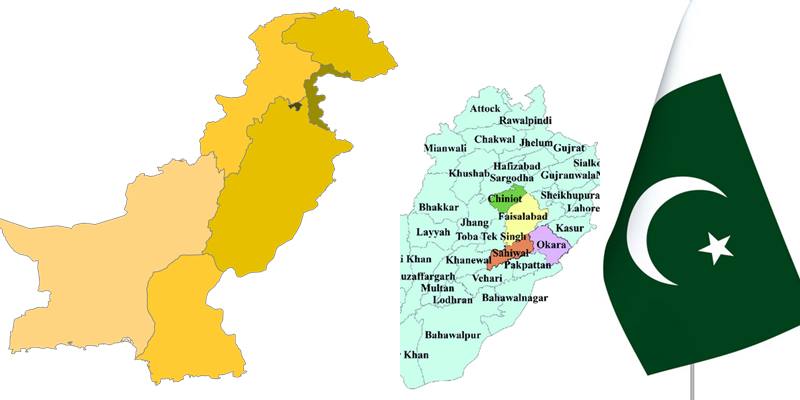

Today there is a fairly well-informed debate taking place on the national media on the creation of Hazara, Seriaki and/or Bahawalpur subas (provinces). There have been a few references to partitioning the Pakhtoon areas of Balochistan and merging them with Khyber_PakhtunKhwa (KPK) province. Poltiical cards have also been played in the name of dividing the Sindh province enabling the creation of Karachi as a separate federal unit. On the latter proposal, the major stakeholder Muttahida Qaumi movement (MQM) has clearly articulated its point of view that it does not want a separate Karachi province.

Demands for another constitutional amendment for new provinces on administrative, ethnic, and linguistic or a combination of all such imperatives have been made. In part this discourse is shaped by the electoral politics of the ruling Pakistan People’s party and its newfound ally the Pakistan Muslim League-Q (PMLQ), which are proponents of a Southern Punjab and Hazara provinces respectively. PMLQ supports both while PPP is using the division of the Punjab as its master card for public mobilization in the next election especially in its likely contest with the Pakistan Muslim League faction led by the Nawaz Sharif.

PPP’s co-chairperson and the President of the country Asif Ali Zardari has proved himself to be a deft player of political cards. Hitherto, the PPP had maximized its unique position as a federalist party and had expressly used the ‘Sindh-card’. However, over the last few months, it is also championing the cause of a Seriaki province. This enables the party to consolidate its electoral support in Sindh and South Punjab. Whilst the northern and central districts of the Punjab are considered to be strongholds of the PMLN, the PPP is attempting to protect its base in the South. Furthermore, it is also eyeing a split vote between the two PMLs in the northern/central constituencies of the province thereby cornering the PMLN. This has been a smart strategy and is likely to keep the debate alive beyond the next election. Similarly, by lending tacit support for a Hazara province, the PPP is also helping PMLQ gain ground in the Hazara dstricts of KPK traditionally aligned with the PMLN.

Neverhtless the issue of creating more provinces should not be restricted to short term electoral gains. There are strong administrative grounds to improve the way provinces are governed. The increase in Pakistan’s population and the intra-provincial inequities are also a matter of public concern. Punjab for instance has a population of over 100 million people. It is simply impossible to rule such a huge province from Lahore and that too through the creaky bureaucratic machinery. The Seriaki belt has complained time and again for not getting adequate development funds as the concentration of development has been in the ‘urban’ areas of the Punjab. Similarly, the relative underrepresentation of South Punjab in bureaucracy is another grievance articulated by its political representatives. The issue of a linguistic and cultural identity is also another factor that augments the case for a separate province. However, there is little consensus on whether there needs to be one or two provinces in the South as the Bahawalpur (a former princely state) has a claim on provincial status. Much more needs to be done beyond the political rhetoric.

The position of Awami National Party (ANP) on a Hazara province is ambivalent thus far. The party had surely moved on from its earlier stance on the indivisibility of KPK but it will not be easy to get a new province going unless there is accommodation either through the integration of federally administered tribal areas (FATA) into KPK and/or inclusion of the Pakhtun districts of Balochsitan.

In terms of economic viability, it has been stated that Hazara province is a feasible proposal given its natural resources and ability to generate revenues. On the other hand, the Seriaki province will be the least viable province due to its agrarian base and positioning in terms of water resources. The Pakhtun belt of Balochistan earns its money through trade with Afghanistan and has coal reserves in the Loralai and Zhob regions, estimated at roughly 200 million tonnes. While it may not fully benefit the long term economic gains of remaining with Balochsitan, it will not be all too worse off by merging with KPK.

Having said that a full-scale economic assessment of the proposed new provinces is also a neglected area that the political parties are yet to take up. In general the political parties have limited technical resources to undertake such analyses; and this is where the civil society, think tanks and academia must step in. Other than the Collective in Karachi very few think outfits have ventured to make such feasibility studies. Such thinking is necessary to shape the political argument and ensure that creation of new provinces may not result into dependent units with elite capture over institutions thereby denuding the entire purpose of administrative reshaping of provinces.

Achieving an agreement on more provinces will not be an easy task. For instance the new provinces will need to handle 47 devolved subjects of the concurrent list. In the absence of finances and limited administrative experience makes the prospects even more complicated. In the past, provinces have resisted the levying of VAT on services given the weak tax machineries and potential socio-political upheaval. However, on the positive side the federal government now has thousands of employees in the surplus pool that could be relocated to the new provinces if the proposals materialize.

There are strong political, cultural and governance arguments for new provinces. At the same time, creation of new provinces requires critical thinking and studying the experience of India, which has now 29 provinces and the process that the country followed whereby relatively peaceful re-shaping of boundaries was accomplished through a political process. Power has been centralized for too long in Pakistan and it has only resulted in nurturing narrow oligarchies and lobbies which profit from centralized rule at the expense of citizen interest. Having said that creation of new provinces without effective local government structures will not lead to improved governance. Power would still remain in the hands of provincial elites. Pakistan needs both decentralization and actual distribution of power that is unattainable without responsive local government system.

In the short term, demands for new provinces will provide a newer arena for politics taking a diverse country such as Pakistan in the right direction. The one-nation, one-faith bogey has not delivered in the six decades of its existence. However, formidable legal, economic and administrative challenges remain which need to be tackled through a national commission as proposed by Mian Nawaz Sharif. A parliamentary commission should look into all these challenges and achieve consensus on the new Pakistan that the civilians badly need to construct.

Raza Rumi is a writer, editor and policy adviser based in Lahore. He blogs at www.razarumi.com and edits www.pakteahouse.net. Contact him via Twitter: @razarumi